Engine Component

Compatibility

to a Manual

Transmission

TOC

TOC

ROB MUNOZ

Wes Allison, Tommy Lee Byrd, Ron Ceridono, Grant Cox, Dominic Damato, Tavis Highlander, Jeff Huneycutt, Barry Kluczyk, Scotty Lachenauer, Jason Lubken, Steve Magnante, Ryan Manson, Jason Matthew, Josh Mishler, Evan Perkins, Richard Prince, Todd Ryden, Jason Scudelleri, Jeff Smith, Tim Sutton, and Chuck Vranas – Writers and Photographers

AllChevyPerformance.com

ClassicTruckPerformance.com

ModernRodding.com

InTheGarageMedia.com

subscriptions@inthegaragemedia.com

Mark Dewey National Sales Manager

Janeen Kirby Sales Representative

Patrick Walsh Sales Representative

Travis Weeks Sales Representative

ads@inthegaragemedia.com

inthegaragemedia.com “Online Store”

info@inthegaragemedia.com

The All Chevy Performance trademark is a registered trademark of In The Garage Media.

ISSN 2767-5068 (print)

ISSN 2767-5076 (online)

Send address changes to In The Garage Media, 1350 E. Chapman Ave. #6550, Fullerton, CA 92834-6550 or email ITGM at subscription@inthegaragemedia.com. Postage paid at Fullerton, CA, and additional mailing offices.

FIRING UP

FIRING UP

BY NICK LICATA

BY NICK LICATAfter about a year of dealing with all sorts of uncertainty due to the pandemic (I’m fine with never hearing that word again), it looks like we are finally getting back to something that resembles some sort of normalcy. Normal in the sense that events and car shows are back, or are going to soon be back in business. As of this writing, it’s late March and we are getting word that most canceled 2020 car shows are back on the 2021 calendar—many with adjusted dates.

That’s great news, as the hot rod and muscle car hobby doesn’t exist exclusively in shops, garages, online, or on social media, although the Web and social media outlets did get us through some tough times while stuck at home dodging a virus.

If you are like me, there is a good chance you are itching to get out to a show, drag race, or any sort of event that involves socializing, driving, and showing your hot rod with like-minded folks.

Parts Bin

Parts Bin BY Nick Licata

BY Nick Licata

CHEVY CONCEPTS

CHEVY CONCEPTS

Text and Rendering by Tavis Highlander

Text and Rendering by Tavis Highlanderinishing details were the task at hand for this 1967 Camaro convertible project. The owner had many of the major elements assembled but deciding how to finish those elements in order to create a cohesive package was somewhat undecided. Working together we were able to visualize colors, materials, and interior shapes quickly and efficiently.

For the exterior, we tested out a dark gray paint scheme with black and carbon details. Rotiform wheels were chosen and finished in gloss black. A fine mesh material was inserted into the hood scoop opening and lower fascia ducts as a finishing detail.

The interior revolved around using late-model GTO bucket seats up front. A dark red leather wraps everything and provides a colorful pop against the subdued gray exterior. TMI door panels with custom inserts keep the fabrication levels in check. The sheetmetal dash, however, is all custom with a Dakota Digital insert. With these appointments, the Camaro is sure to make for a comfortable street cruiser.

FEATURE

FEATURE

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authort doesn’t matter what era you’ve grown up in since the mind of a young hot rodder is always at work. Regardless of whether you’re sitting in class or daydreaming in the lunch room, you’re always making plans to build the ultimate hop-up. Many times the dreams are just that, often staying locked up with hopes that they might get nudged into reality as soon as an opportunity arises. For Alex Finigan of Marblehead, Massachusetts, he didn’t get to build the 1955 Chevy he envisioned in 1965 while attending high school until now, and all we can say is it was worth the wait!

TECH

TECH

Photography by the Author

Photography by the Authorelaying information about the engine to the driver was never really of huge importance to Chevrolet or the other OEMs. They figured a temp gauge was worthy of being in most instrument clusters and maybe a couple warning lights, just in case.

Case in point is the dash of a 1955 or 1956 passenger car. A temp gauge, with the values of simply C and H, was included in the dash along with the fuel gauge placed above the speedometer span. A warning light would glow to let you know there was no way the car would start again, as the generator was not charging. If the oil psi warning light came on, it was likely to let you know that something very expensive just failed. No tach, no voltage, no oil pressure, not even as an option. This is why hot rodders have always hung a few gauges under the dash.

Photography by the Author

Photography by the Authorelaying information about the engine to the driver was never really of huge importance to Chevrolet or the other OEMs. They figured a temp gauge was worthy of being in most instrument clusters and maybe a couple warning lights, just in case.

Case in point is the dash of a 1955 or 1956 passenger car. A temp gauge, with the values of simply C and H, was included in the dash along with the fuel gauge placed above the speedometer span. A warning light would glow to let you know there was no way the car would start again, as the generator was not charging. If the oil psi warning light came on, it was likely to let you know that something very expensive just failed. No tach, no voltage, no oil pressure, not even as an option. This is why hot rodders have always hung a few gauges under the dash.

FEATURE

FEATURE Photography BY Dominick Damato AND Matt Landford

Photography BY Dominick Damato AND Matt Landford

ony Certoma was on the hunt for a rust-free 1970 Chevelle. Not an easy task, today, especially if you live in Melbourne, Australia, as Tony does. It’s not like he can just wing over on a whim to scour America for the perfect specimen. That sort of thing takes time and you have to know the right people. This is where Jeff Schwartz comes in. Schwartz has been in the chassis and muscle car building biz for over 20 years, so he’s connected—he’s got juice. Schwartz put out an APB to his muscle car network for a rust-free 1970 Chevelle—preferably one with lineage to California. He was soon introduced to a ripe example found in Wisconsin—not too far from Schwartz Performance in Woodstock, Illinois. Somewhat leery on the car’s condition due to its location, Schwartz did some research and found the car to have spent a majority of its life in California—a stark contrast to the rough metal-eating conditions the car would have endured living in the Midwest. Schwartz informed Tony of the find and sent him a few photos for reference. Tony approved. A fan of vintage muscle cars, but not the temperamental aspects that sometimes accompany owning a classic, Tony and Schwartz put a plan together to build a stout and reliable street machine. Unforeseen budget constraints prolonged the build, which took almost 10 years, and by 2020 the car was ready. Tony was champing at the bit to get behind the wheel and tour America in his vintage ride, but with the arrival of COVID-19 so did a travel ban that left Tony stranded in the land Down Under. The cruise across America would have to wait. But Schwartz, armed with motivation, the ultimate set of tools, and years of experience, kept busy setting up the Chevelle with all modern bits to ensure Tony can twist the key and motor down the road with no issues.

TECH

TECH BY ACP STAFF

BY ACP STAFFhere’s nothing more rewarding than bringing a cool car out of mothballs and putting it back on the road. Ironically, one of the temptations that we enthusiasts have to fight off is the urge to tear such a garage queen apart and rebuild it from the ground up. That often ends up with the car sitting for an even longer period of time in project jail. A better option is to make that rediscovered gem reliable so it can be driven and enjoyed first, then make updates as time and your budget allows.

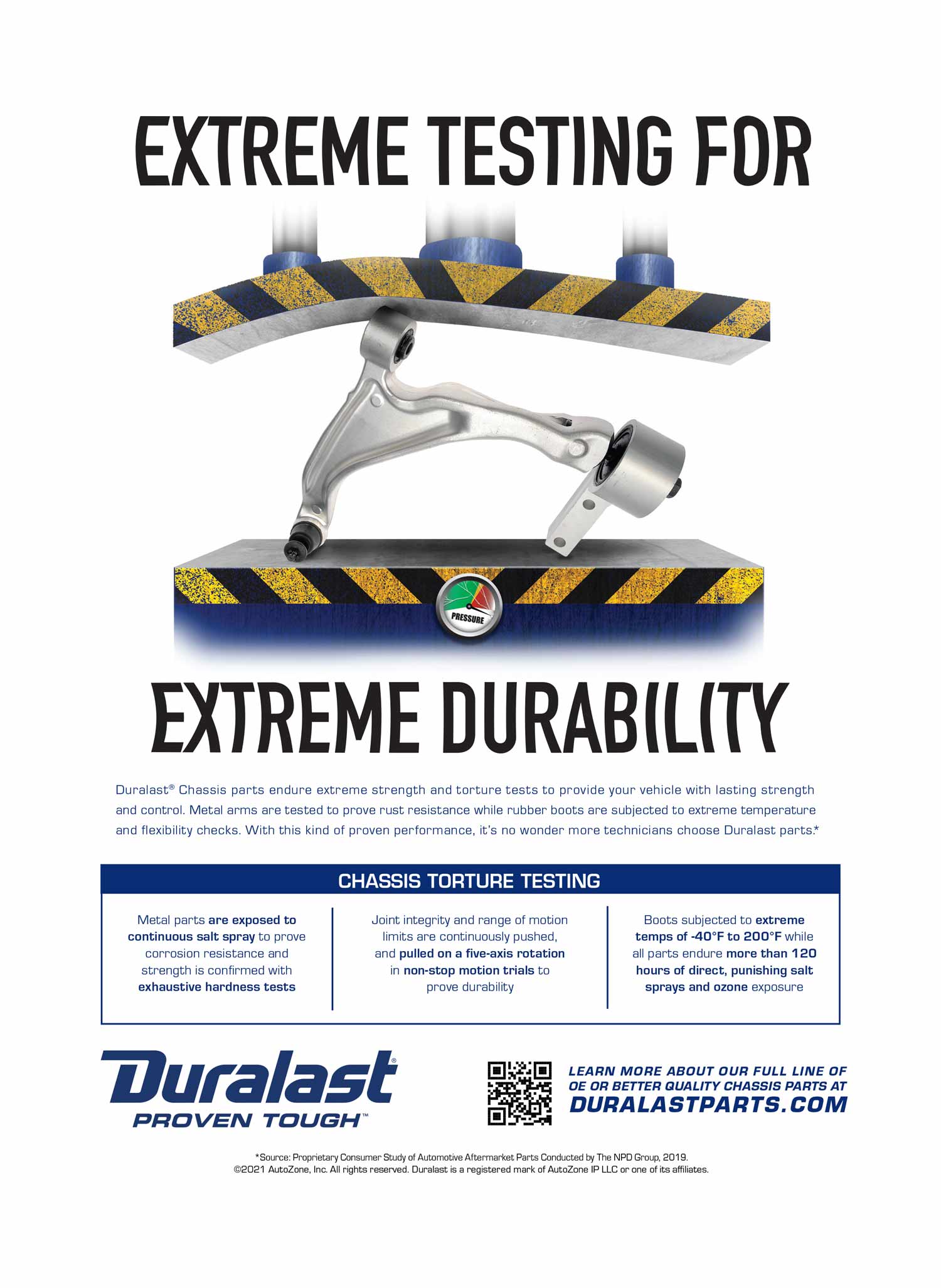

Like most cars that have been sitting for an extended period, time had not been particularly kind to the 1964 Chevelle shown here. A number of critical components have deteriorated over the years and will have to be replaced to ensure reliability. Typically, those parts are starting, ignition, and cooling system related. Fortunately, installing any of those items isn’t difficult to do and they are readily available from Duralast.

FEATURE

FEATURE Photography by Jason Matthew

Photography by Jason Matthew W

We found a great-looking 1970 Rally Sport in Citrus Green with black SS stripes on eBay. It had a 350 small-block with World heads, a Demon carb, and headers, along with some other work done. The seller attached a video showing the car running and sounding strong, so we decided to buy it. When the car was delivered from Michigan, we pulled it off the trailer and tried to start the car. It just backfired and wouldn’t start.”

These are the words from Anna-Maria Parinello. We’ve heard similar stories on more than one occasion, and we’ve even been victim to a similar ordeal. It’s the same old thing, someone on the Internet is selling a car they no longer want to mess with and advertise it as better-looking, better-running, and just plain better overall than it really is.

W

We found a great-looking 1970 Rally Sport in Citrus Green with black SS stripes on eBay. It had a 350 small-block with World heads, a Demon carb, and headers, along with some other work done. The seller attached a video showing the car running and sounding strong, so we decided to buy it. When the car was delivered from Michigan, we pulled it off the trailer and tried to start the car. It just backfired and wouldn’t start.”

These are the words from Anna-Maria Parinello. We’ve heard similar stories on more than one occasion, and we’ve even been victim to a similar ordeal. It’s the same old thing, someone on the Internet is selling a car they no longer want to mess with and advertise it as better-looking, better-running, and just plain better overall than it really is.

TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

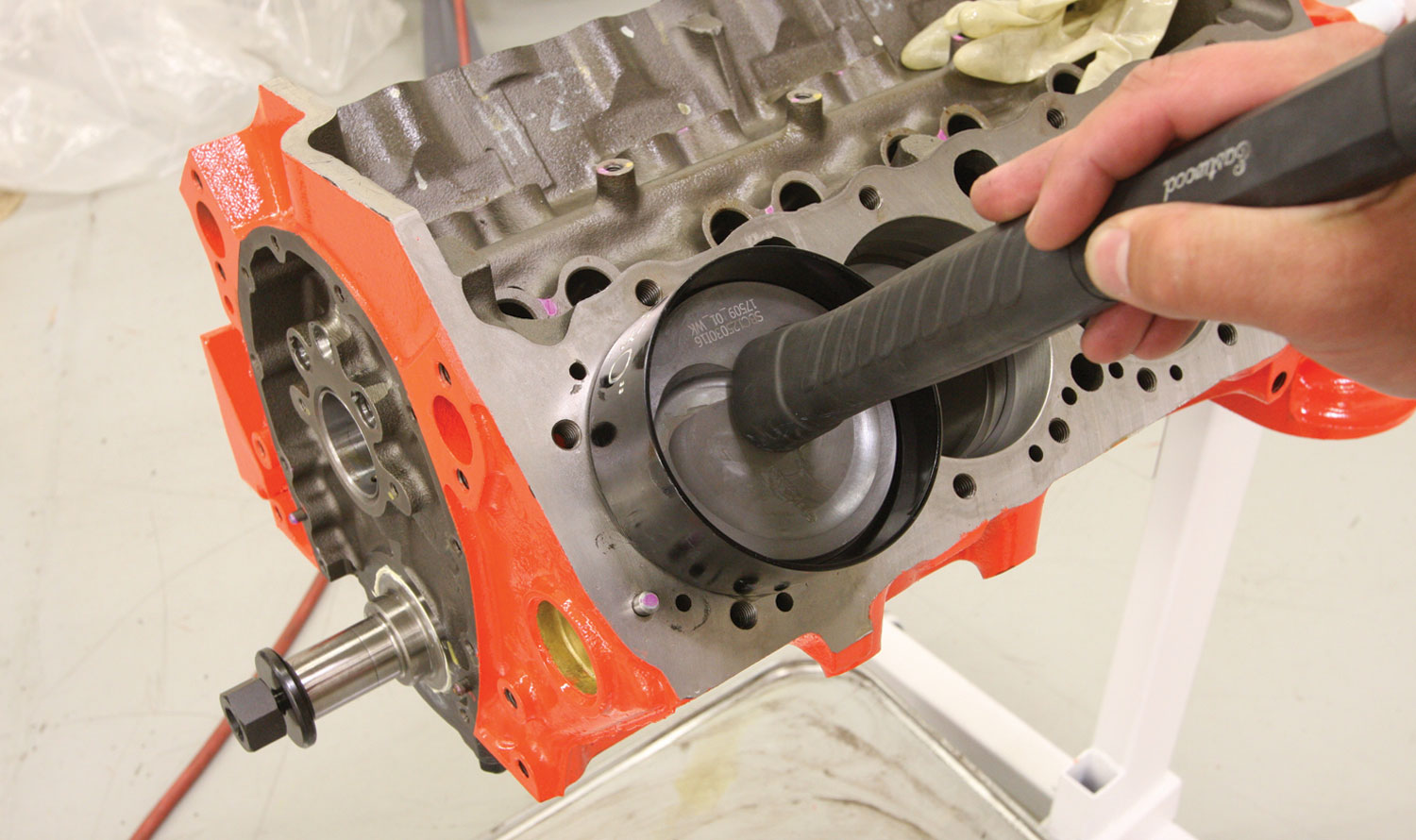

Photography by The Authorhen it comes to assembling an engine, it’s not uncommon to find yourself mixing and matching components of unknown origin. Perhaps it starts with a junkyard engine that’s been torn down to the bare block, or maybe it’s a half-finished engine build inherited from a friend. The specifics are supposed to be XYZ, but what are they in reality?

Without properly measuring everything, it’s nearly impossible to guarantee that the components will work together or are even what they’re supposed to be. The block could have been bored or honed, the pistons ordered oversized or otherwise incompatible. It’s not uncommon to pick up a set of decent pistons from a swap meet that seem like the perfect forgings for that low-buck 350 build, but if they won’t fit your block you could be looking at spending more money to get those “sweet deal” parts to actually work together. In all of these cases, your best bet is to measure twice and purchase once.

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorhen it comes to assembling an engine, it’s not uncommon to find yourself mixing and matching components of unknown origin. Perhaps it starts with a junkyard engine that’s been torn down to the bare block, or maybe it’s a half-finished engine build inherited from a friend. The specifics are supposed to be XYZ, but what are they in reality?

Without properly measuring everything, it’s nearly impossible to guarantee that the components will work together or are even what they’re supposed to be. The block could have been bored or honed, the pistons ordered oversized or otherwise incompatible. It’s not uncommon to pick up a set of decent pistons from a swap meet that seem like the perfect forgings for that low-buck 350 build, but if they won’t fit your block you could be looking at spending more money to get those “sweet deal” parts to actually work together. In all of these cases, your best bet is to measure twice and purchase once.

Feature

Feature PHOTOGRAPHY BY THE AUTHOR

PHOTOGRAPHY BY THE AUTHOR

t’s common for a car guy to seek a change of pace at some point in his life, and we’ve seen that go both ways—some want to go faster and some want to slow down. Others, like Dave Kaveshan, simply want to try something different. He drag raced for many years, and he must’ve gotten tired of doing wheelies in his supercharged 1965 El Camino because that project was sidelined in favor of the corner-carving 1962 Chevy II seen here. As it turns out, the wheelstands and wild rides were pretty rough on the bank account, so Dave jumped full force into a car that would be a little easier on parts but still put a smile on his face. The important part of this equation is that he could now enjoy car crazy adventures with his wife, Crystal, alongside in the passenger seat.

TECH

TECH Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorob Dylan once wrote “… the times they are a-changin’.” He probably didn’t have electronic fuel injection in mind when he wrote those words, but it is certainly true that there’s been a rich mixture of changes with aftermarket electronic fuel injection in the last 10 to 15 years. It wasn’t all that long ago that most car guys steered clear of electronic control over fuel and spark but with a tremendous variety of high-quality systems on the market and the opportunities they offer have made believers out of at least a few serious doubters.

But we have to admit that this conversion to electronic control has not been easy. There has also been a smattering of challenges to make these systems operate smoothly. It doesn’t take much effort to find negative comments about every system out there. While it’s easy to blame the manufacturers, our experience with many of these systems is that there are often simple solutions to many of these difficulties. We’re not going to blow smoke in your face and claim that all these systems work flawlessly. That’s just not true.

However, we will stand firm on the belief that many of these systems will operate well and offer respectable returns on the investment as long as certain rules are followed and an effort to undo these difficulties is attempted. In our experience, it’s often simple installation errors or an occasional failed sensor that is to blame. But if you follow the instructions—yes you must read the instructions carefully—likely you can avoid many of the pitfalls that plague those installers who just don’t make the effort to do the job correctly.

Feature

Feature Photography BY The Author

Photography BY The Authoro hard-core vintage muscle car freaks, the name Brian Henderson should pop a light bulb off in your Chevy-crazed cranium. Brian is a well-known muscle car historian and co-owner of Super Car Workshop (SCW) in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, a restoration shop that specializes in restoring big-money muscle rides from GM’s glory days of the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Working along with partner Joe Swezey, the twosome has kept up the search for Chevy’s big-powered rides of the first muscle car era, hunting down, verifying, and restoring those rare Bowties. To date, the twosome doesn’t have a precise count on how many Chevys they’ve recovered and restored, as the boys have run out of digits to count on. “All we can say is that we’ve been very prolific,” Brian quips.

TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

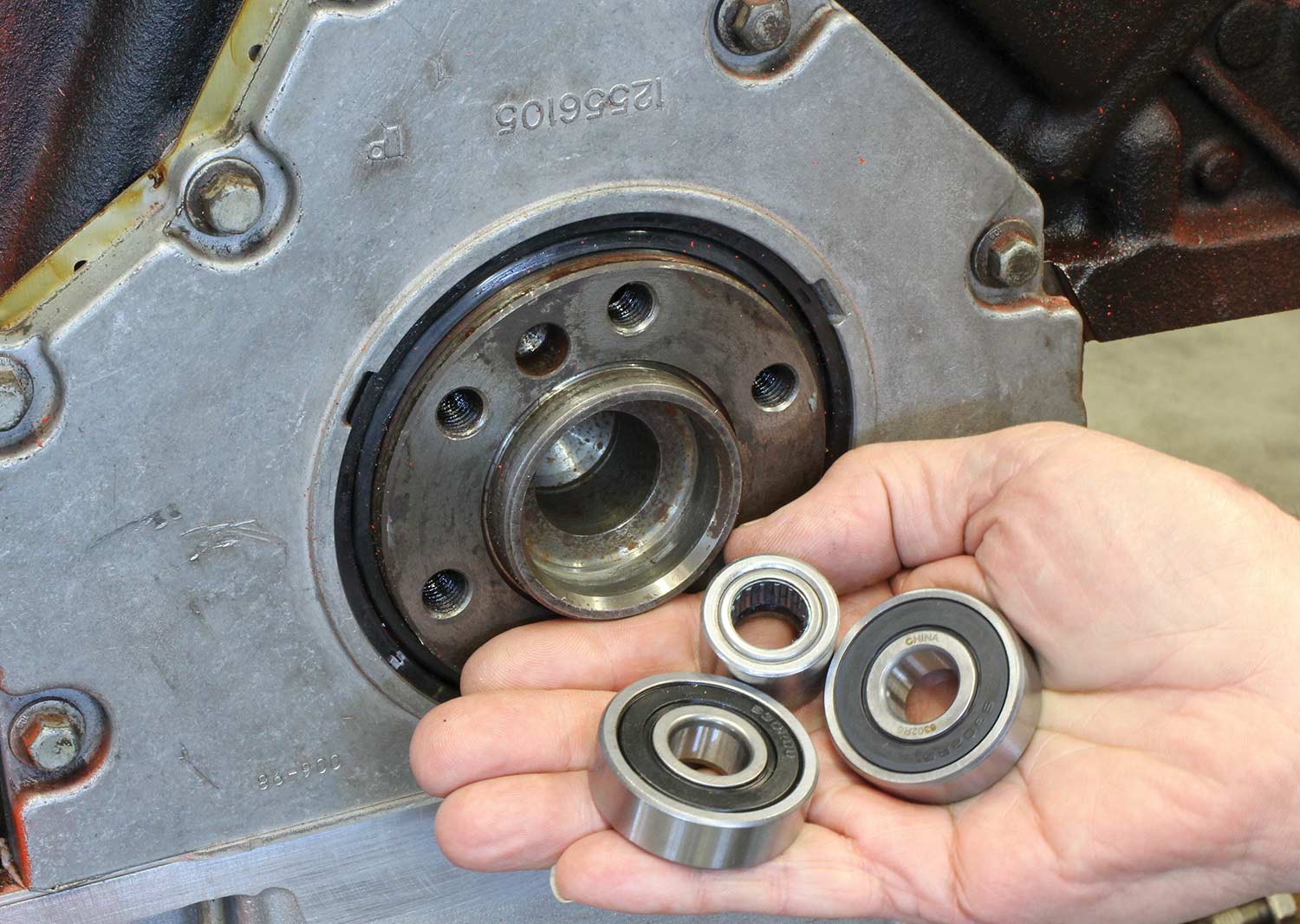

Photography by The Authorhe devil is in the details may be an over-used cliché, but it nevertheless has a very practical side to it. Car builders since the beginning of automotive time have been the innovators who prefer to build their machines in much the same way that Dr. Frankenstein built his monster—using parts from departed souls.

In this particular case, we’re talking about combining manual transmissions between the original Gen I small- and big-block Chevys and its Gen III/IV LS cousin. Everyone knows that the LS bellhousing bolt pattern is the same (with one relocated bolthole). That makes adding a manual transmission a simple, bolt-in deal, yes?

The devil of it is, it’s not that simple.

Our friends at TREMEC, Bowler Transmissions, and Centerforce have teamed up to create a roadmap for engine swappers because there are some serious misapplication errors that can occur that carry with them dire consequences if the important details are not given their due. All this revolves around the proper placement of the LS pilot bearing. Centerforce’s Will Baty informed us that there are actually three different pilot bearings for the LS engine and each one must be properly matched with the correct transmission. That’s what this story is all about.

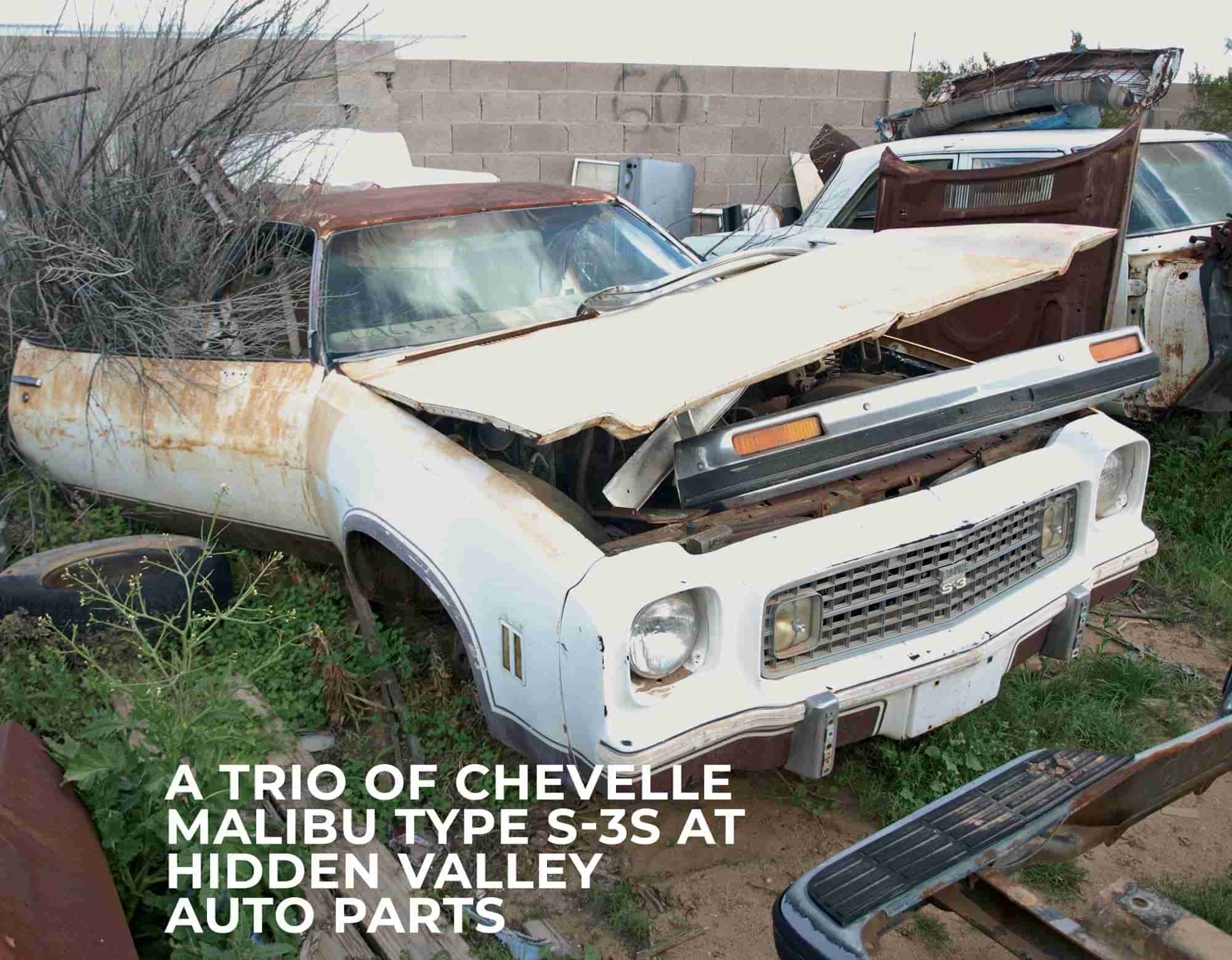

BOWTIE BONEYARD

BOWTIE BONEYARD

Photography BY THE AUTHOR

Photography BY THE AUTHORhen they first appeared with their squared-off lines and chunky energy-absorbing bumpers, the 1973 Chevelle line was a radical departure from the more rounded 1968-1972s. Built to appease federal safety zealots, GM designed the all-new midsize A-body platform with an eye toward accident protection. As such, all roof pillars grew in thickness, fabric-topped convertibles were eliminated, and hydraulic rams allowed the aforementioned energy-absorbing bumpers to slowly return to pre-impact condition within 24 hours (as long as the impact was 5 mph or less).

At the top in 1973 was the so-called Laguna, which showcased GM’s growing interest in molded urethane endcaps for the front end of the body. While lesser Deluxe and Malibu models got massive chrome front bumpers and somewhat conventional metal grille openings, the Laguna (which was offered on all body styles, including station wagons in 1973) came with one-piece, body-colored fascias that integrated the bumper and shrunk the grille into a pouting orifice containing the turn signals. The effect was slick and looked like it was pulled from a mold—which it was.

While the SS option (RPO Z15, $242.75) could be had one last time in 1973 (including station wagons!) with any V-8 engine, 1974 brought something familiar, yet new—the Laguna Type S-3. Offered only on two-door Laguna coupes, the Type S-3’s metal identification emblems used fonts and colors that emulated the classic SS badges of previous years. In fact, from a distance, the S-3 and SS emblems look nearly identical. Chevrolet never revealed what exactly “Type S-3” meant, but no doubt took inspiration from Jaguar’s “E-Type” nomenclature to capture a European flair.