Conversion,

Part 1

Using Early

Second-Gen

Sheetmetal

on a ’78

1,200hp 5.3L

Short-Block

Using Early Second-Gen Sheetmetal on a ’78

TOC

TOC

Photo by Tommy Lee Byrd

378 E. Orangethorpe Ave. Placentia, California 92870

#ClassicPerform

Wes Allison, Tommy Lee Byrd, Ron Ceridono, Grant Cox, Dominic Damato, John Gilbert, Tavis Highlander, Jeff Huneycutt, Barry Kluczyk, Scotty Lachenauer, Jason Lubken, Steve Magnante, Ryan Manson, Jason Matthew, Josh Mishler, Evan Perkins, Richard Prince, Todd Ryden, Jason Scudellari, Jeff Smith, Tim Sutton, and Chuck Vranas – Writers and Photographers

AllChevyPerformance.com

ClassicTruckPerformance.com

ModernRodding.com

InTheGarageMedia.com

Travis Weeks Advertising Sales Manager

Mark Dewey National Sales Manager

Patrick Walsh Sales Representative

ads@inthegaragemedia.com

inthegaragemedia.com “Online Store”

For bulk back issues of 10 copies or more, contact store@inthegaragemedia.com

info@inthegaragemedia.com

Copyright (c) 2022 IN THE GARAGE MEDIA.

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

FIRING UP

FIRING UP

BY NICK LICATA

BY NICK LICATA

generally try to stay away from current events when it comes to writing this monthly editorial; as luck would have it, I’d start commenting or complaining about the price or situation of something, and when this magazine issue drops two months later, my point becomes moot due to a change of course in the subject addressed. But with today’s high cost of fuel, I’ll take a chance, as I don’t see change coming anytime soon.

As of now (March 2022), in Orange, California, the price of “the good swill” (the higher-octane stuff) we muscle car people need to quench the thirst of our horsepower-greedy hot rods is between $6.39 and $6.51 per gallon. And to think just a few months ago, I verbally complained to myself (because no one else would listen) when I had to pay around $4.80 per gallon.

Like most of us muscle car folks, I don’t use my Camaro as a daily commuter for a couple of reasons; one being having to worry about someone parking too close to my car only to open their door while fully focused on their phone instead of the ding they are about to put on my quarter-panel. Once in a while, I do get it out for a quick run to the grocery store, but sparingly due to the possibility that the one and only runaway shopping cart will somehow find its way to my driver side door. Vintage muscle cars tend to be magnets to that sort of thing.

Parts Bin

Parts Bin

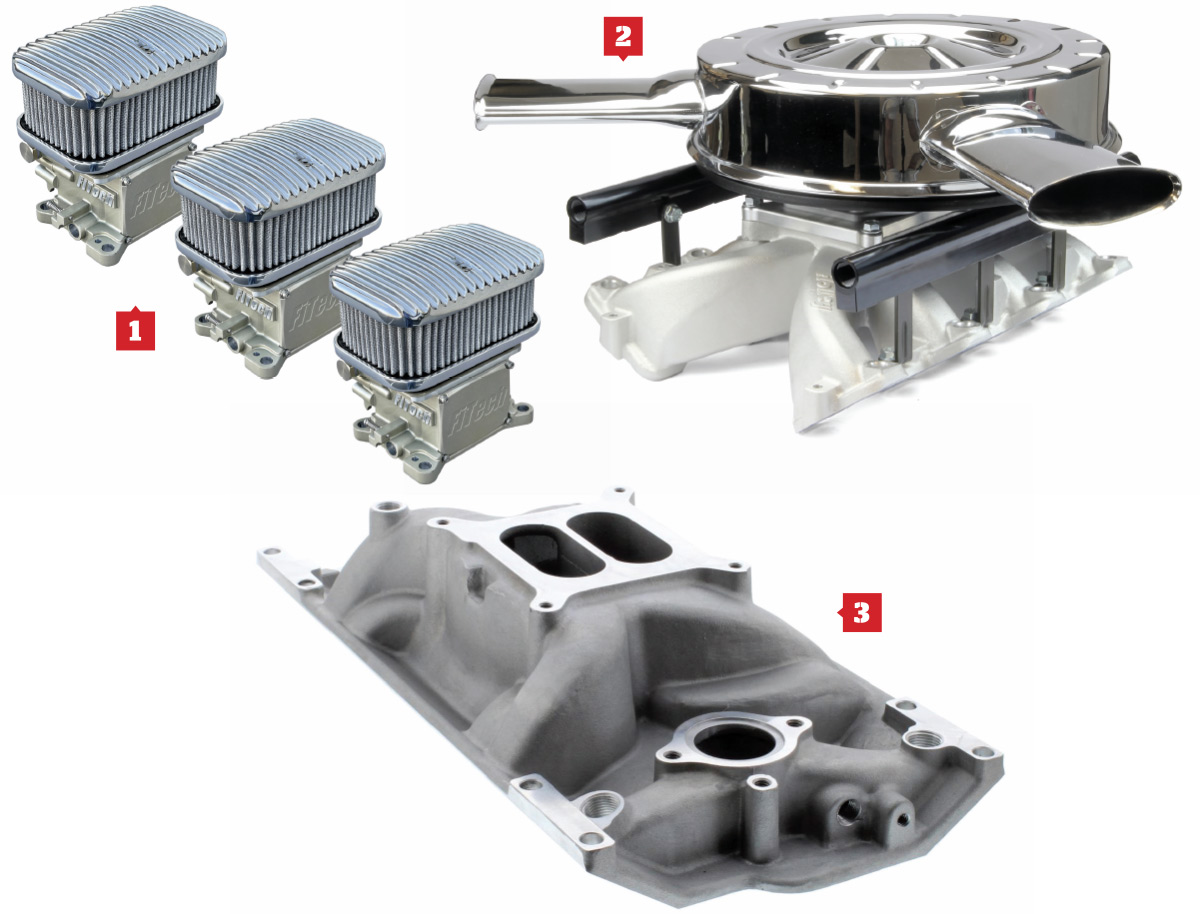

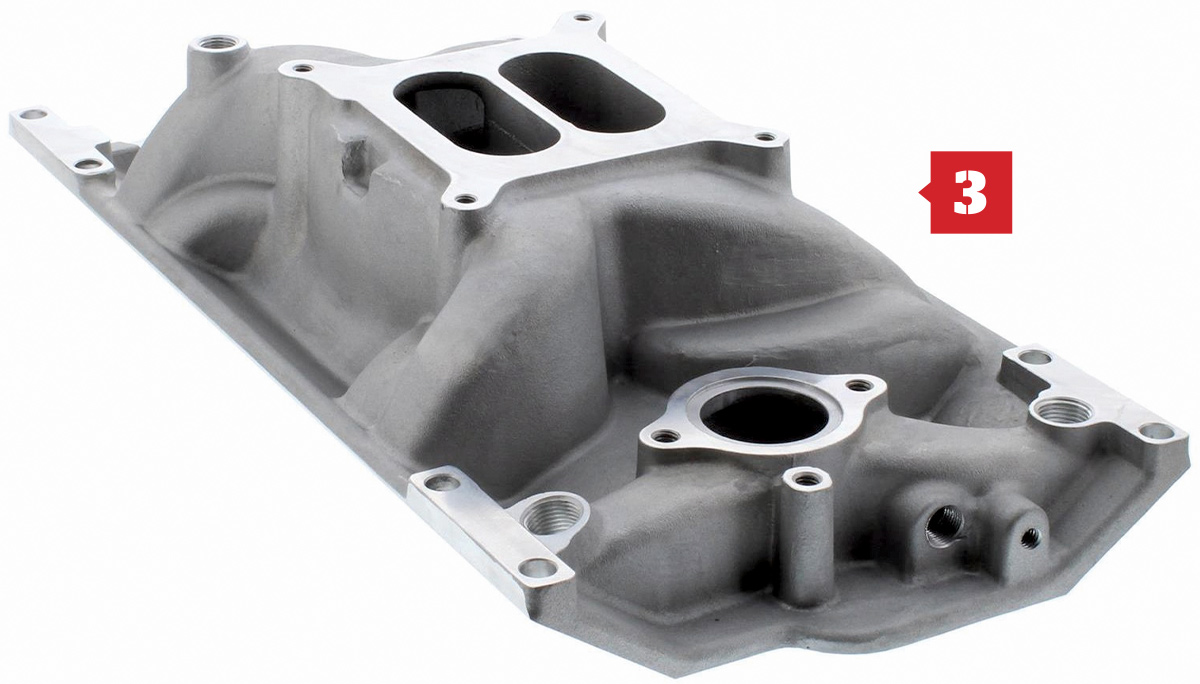

For more information, contact FiTech by calling (951) 340-2624 or visit fitechefi.com.

For more information, contact Lokar by calling (877) 469-7440 or visit lokar.com.

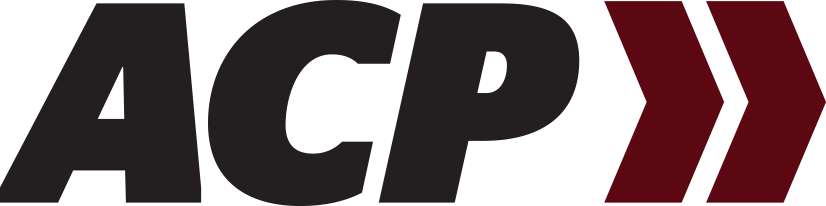

For more information, contact Summit Racing by calling (800) 230-3030 or visit summitracing.com.

CHEVY CONCEPTS

CHEVY CONCEPTS

Text & Rendering by Tavis Highlander

Text & Rendering by Tavis Highlanderhe boys at Born Vintage Hot Rods know how to put their own brand of styling “seasoning” on every build that rolls through their shop. One of the latest projects, a ’69 Camaro, is no exception with just the right amount of spiciness. That attitude comes from many elements, but the custom tube chassis equipped with Heidts IRS is the backbone of the build. A built LS7 backed by a TREMEC six-speed offers up the go while Wilwood brakes bring the slow.

The stance will be nice and low thanks to that tube chassis. A set of Forgeline VX1S monoblocks tuck into the fenders and are finished in a satin charcoal. Custom-machined hood vents now face forward and act as mini scoops. All these subtle little bits add up to another build with substantial character.

Feature

Feature

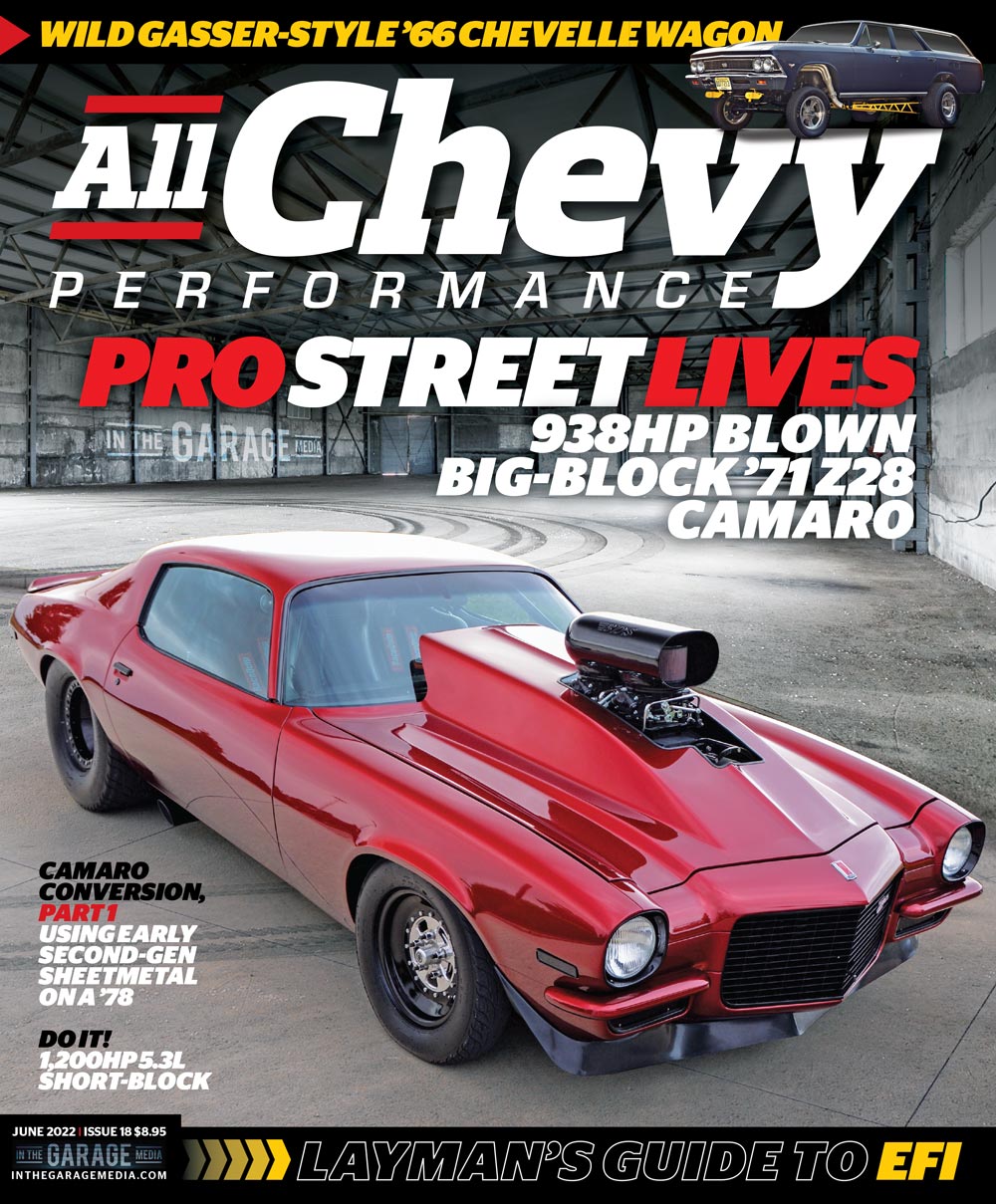

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorro Street got its start with the idea of implementing features from a Pro Stock drag car into a vehicle that could be driven on the street. After about 20 years of evolution and innovation, the Pro Street movement lost a lot of its popularity, largely because of the lack of actual performance associated with these fat-tired freaks of nature. However, a dedicated following has kept Pro Street alive and, if anything, it’s gone back to its radical roots with excessive horsepower and tire-torching capabilities. This incredibly brutal ’71 Camaro Z28 is a fine example of modern Pro Street goodness, as it boasts giant rear tires and four-digit horsepower to match the aggressive drag car appearance.

TECH

TECH BY All Chevy Performance Staff

BY All Chevy Performance Staff

he collector car market continues to grow year after year, making a lot of the cars we know and love harder to obtain. While spit balling one night, The Installation Center owner Craig Hopkins and friend Bill Crabtree were hanging out after a long day’s work and started discussing this very topic. In the background sits a derelict ’78 Chevy Camaro. Hopkins looks at Crabtree and sees the wheels turning. Hopkins asks, “What’s the scheme?” This is where it gets good. Crabtree suggests, “Why can’t we take that old Camaro and turn it into a steel bumper car?” Hopkins, with his vast experience, immediately knew that this had to be done. Why not? The ’74-81 Camaro is vastly more available than that of the ’70-73 cars. Anyone who has restored an early second-gen Camaro knows that the entry point on one of these cars continues to climb. Crabtree continues, “If we can swap the front and rear and turn that car into an earlier version, that opens a whole realm of cars available at a considerable cost reduction.”

FEATURE

FEATURE

Photography BY John Jackson

Photography BY John Jackson TECH

TECHInTheGarageMedia.com

BY Ryan Manson  Photography by The Author

Photography by The Author

Understanding the Terms, Sensors, and Systems

lectronic Fuel Injection (EFI) systems can be a daunting mystery of sensors, wires, and components to those of us with a more “analog” background. Tuning by turning screws or swapping jets might seem second nature to some, but when it comes to fuel maps, electronic sensors, and laptop tuning, it starts to seem more like rocket science. But a familiarity to the science behind how an EFI setup works isn’t completely necessary to understand the gist of such a system. A basic understanding of the sensors involved and what they do and how they communicate with the computer (ECU) to provide the necessary fuel requirements can go a long way to gaining a grasp of how a modern EFI system works.

FEATURE

FEATURE

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Author

utomotive tastes come in various forms and are often influenced by those around us. For many of us, once that interest is ignited, a lifelong journey begins. In Lou Jasper’s case, his late Uncle Joey ignited his passion for all things automotive. He recalls, “When I was about 5 years old, he pulled into our driveway in a ’71 ’Cuda. It had a 440 with a six-pack and I thought it was the greatest car.” By 15 he was wrenching on a 400 small-block to drop into a ’77 Chevelle, however, at that age his mind was set on something smaller and lighter, and he eventually landed a Fathom Green ’69 Camaro. “It looked good from about 20 feet,” he explains. “It had rust in the quarters and floor and the trunk was rusted out.” He eventually put the restomod-flavored Camaro on the road with the 400 and often indulged in some drag racing at Maryland’s 75-80 Dragway. It saw very limited use during his college years, and it wasn’t until his family and career were in place that he was able to get back to it. A new house allowed him to finally store the car, but a month after moving it there, he went for a ride and parked it at a train station–that was the last time he saw it. “I parked it there for the day, when I came back it was gone,” he recalls. That theft was devastating, and as a result his appetite for most things automotive soured.

TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorhe LS engine has long been the king of high-output budget builds. Grab a junkyard truck engine, add a cheap turbo, and make quadruple-digit power. We start our supercharged 1,200hp LS build with a short-block capable of considerable, reliable power on a budget.

There are millions of forum pages dedicated to the topic of LS budget builds, so tread lightly. The sloppy fans will tell you the true budget LS is one that goes straight from the junkyard in between the fenders of your hot rod. There’s some truth to that, as the LS features many architectural improvements over its predecessor, the small-block Chevy. Advancements include a Y-block design with six main bolts (four vertical, two horizontal), extra-long head bolts, a taller deck, better flowing heads, larger cam journals, and a cam centerline that’s higher in the block. “The GM engineers have done a very good job. If you don’t get too far off the map from OE, you shouldn’t have to make many more changes,” Dennis Borem, owner of Pro Motor Engines (PME) says. “These engines are built to last hundreds of thousands of miles.”

Record chasers have made around 1,200 estimated flywheel horsepower with stock bottom ends, and around 1,800 hp with stock blocks. But, we want this engine to remain versatile with the ability to street drive and use for later testing, so we need a better rotating assembly that can reliably handle the abuse. “You can make that kind of power with a stock engine, but it takes a very skilled tuner and an optimized setup,” Tick Performance owner Jonathan Atkins says, who volunteered to build this engine in conjunction with PME. “The better rods and pistons may survive a tuning misstep that stock parts would not, but really they’ll perform better and last much longer.”

It seems 1,200 hp is that rough maximum for the basic aftermarket support. “When you start climbing over that power range, the price of the components goes significantly higher,” Atkins says. Companies like Summit Racing and ARP make bolt-in components to help bring us to that level of reliable power.

FEATURE

FEATURE

InTheGarageMedia.com

By Scotty Lachenauer  Photography by The Author

Photography by The Author

oey Dean has always been a big fan of ’66 Chevelles. In 2009 he came across a rust-free Chevelle wagon from California and he instantly fell in love. It was something different and he knew right away that he had to have it.

Joey has always enjoyed building things that were unique to what the other guys were doing. “I started as a youngster with Legos, erector sets, and model cars. I graduated to garbage picking bikes and rebuilding them and then moved onto go-karts and minibikes. When I went to the 1974 New York Auto Show, it was a big mind-bender. It all was influential and still inspires me when I build my hot rods today,” Joey states.

Like many of us, Joey’s love of all things Chevy commenced at a very young age. “Both my older sister and brother had ’68 and ’69 Camaros as their first cars,” Joey remembers. “That made me want a Camaro of my own.” However, it was another hot ride that finally gripped Joey’s heart and just wouldn’t let go. After spotting his neighbor’s boyfriend rolling up in a sweet ’66 396 SS Chevelle, his love affair with that year and model took off.

Special FEATURE

Special FEATURE

Photography by Tommy Lee Byrd, Grant Cox, Ryan Miller, Scotty Lachenauer, Richard Prince, Chuck Vranas & Todd Ryden

s time moves forward it tends to distance itself from historical accuracy. In the vintage muscle car world [we] have a plethora of documentation through good old-fashioned magazines from the early days of hot rodding, but while the images hold visual truth, the spoken words of those present at the time tend to become a bit distorted as the stories get passed down from generation to generation—not intentional, it’s just a natural progression, or regression in this case.

As the history of vintage muscle cars remain anchored in time, it further distances itself from its origin. This separation can sometimes lend itself to muscle car terminology becoming a bit askew. But let’s keep in mind that while muscle car modifications shift, so should the definitions.

So, we’ve reached out to a few knowledgeable and respected industry gearheads who have been on the editorial side of the car magazine world for decades to get their interpretation of some terminology common with muscle car build styles, and if said terms are subjective, standardized, or simply need a bit of updating.

In part one of our terminology series, we’ll introduce our panel of experienced hot rod types and let them share their interpretation of Day Two Restos and Restomods. As always, we encourage you to chime in with your thoughts, so send an email to: nlicata@inthegaragemedia.com.

TECH

TECHInTheGarageMedia.com

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorrom the day of the first dead car battery 100 years ago, resuscitating a flat battery requires a set of jumper cables, a secondary power source (like another car), and sufficient room to place the cars close enough to connect the cables. Even then, the effort was not always successful. Often, cables were either too short or featured such tiny cables that amperage just didn’t flow, and the inert battery remained flat. Worse yet was the feeling of helplessness when you’re standing there with jumper cables in your hand and no one offers to help.

All of that should now be placed firmly in the past. With the development of powerful lithium-ion batteries, a sharp engineer came up with the idea to build a portable battery pack that could fit in your hand with enough power to crank a near-dead battery even when hooked to a large V-8 engine. When these units first appeared, we were skeptical, but performance has actually proven their worth. We’ll take a look at how these units can deliver tremendous starting power from a small package. We chose one of Antigravity’s XP-10 jump packs from Summit Racing as our test unit.

FEATURE

FEATURE

Photography by Jason Matthew

Photography by Jason Mattheweing an enabler is typically considered a bad thing when it comes to unhealthy addictions, but if it’s your pops and grandpops doing the pushing, it’s likely to be something positive. In the case of John Griffith III, he pretty much had little choice in the matter when it came to the horsepower addiction. “I inherited the affection for power from my father and grandfather,” John admits. “It started with motorcycles in my early teenage years, then naturally grew in the direction of muscle cars soon after.”

That passion gripped John pretty hard, so he aimed that spirit toward building something vintage. He was particularly fond of the attitude associated with a classic Chevelle. “My dad’s friend, Rob Concato, built a ’67 for drag racing back in the early ’00s and he eventually sold it to a guy in Maryland,” John says. “After a few years the guy wasn’t doing much with the car and was willing to sell it to me, so I jumped on it.

“When I got the car it was in fair condition but was bare bones and needed some modern upgrades and a lot of attention cosmetically,” John remembers. “It had a simple interior, poor turning radius, and ill-equipped brakes. Going straight was about the only thing it did well.”

Advertiser

- American Autowire27

- Art Morrison Enterprises59

- Auto Metal Direct41

- Automotive Racing Products45

- Borgeson Universal Co.57

- Bowler Performance Transmissions87

- Classic Industries55

- Classic Instruments75

- Classic Performance Products4-5, 85, 92

- Concept One Pulley Systems85

- Dakota Digital91

- Duralast9

- FiTech EFI75

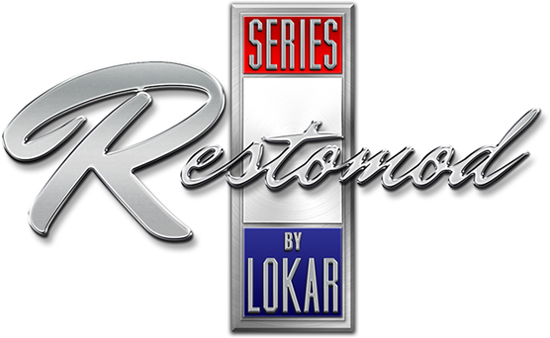

- Golden Star Classic Auto Parts7

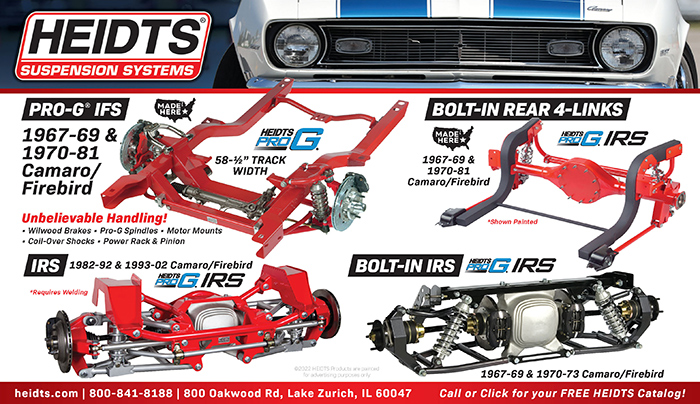

- Heidts Suspension Systems71

- Lokar2

- National Street Rod Association69

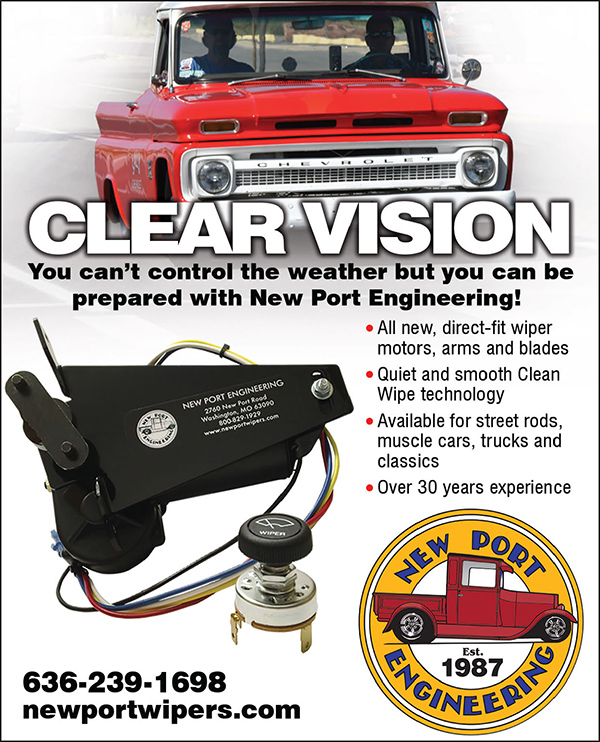

- New Port Engineering87

- Original Parts Group23

- PerTronix29

- Powermaster Performance79

- Roadster Shop43

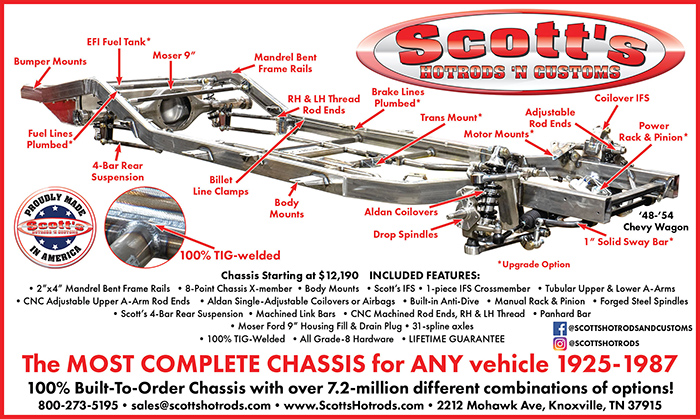

- Scott’s Hotrods79

- Speedway Motors31

- Summit Racing Equipment11

- Thermo-Tec Automotive85

- Vintage Air6

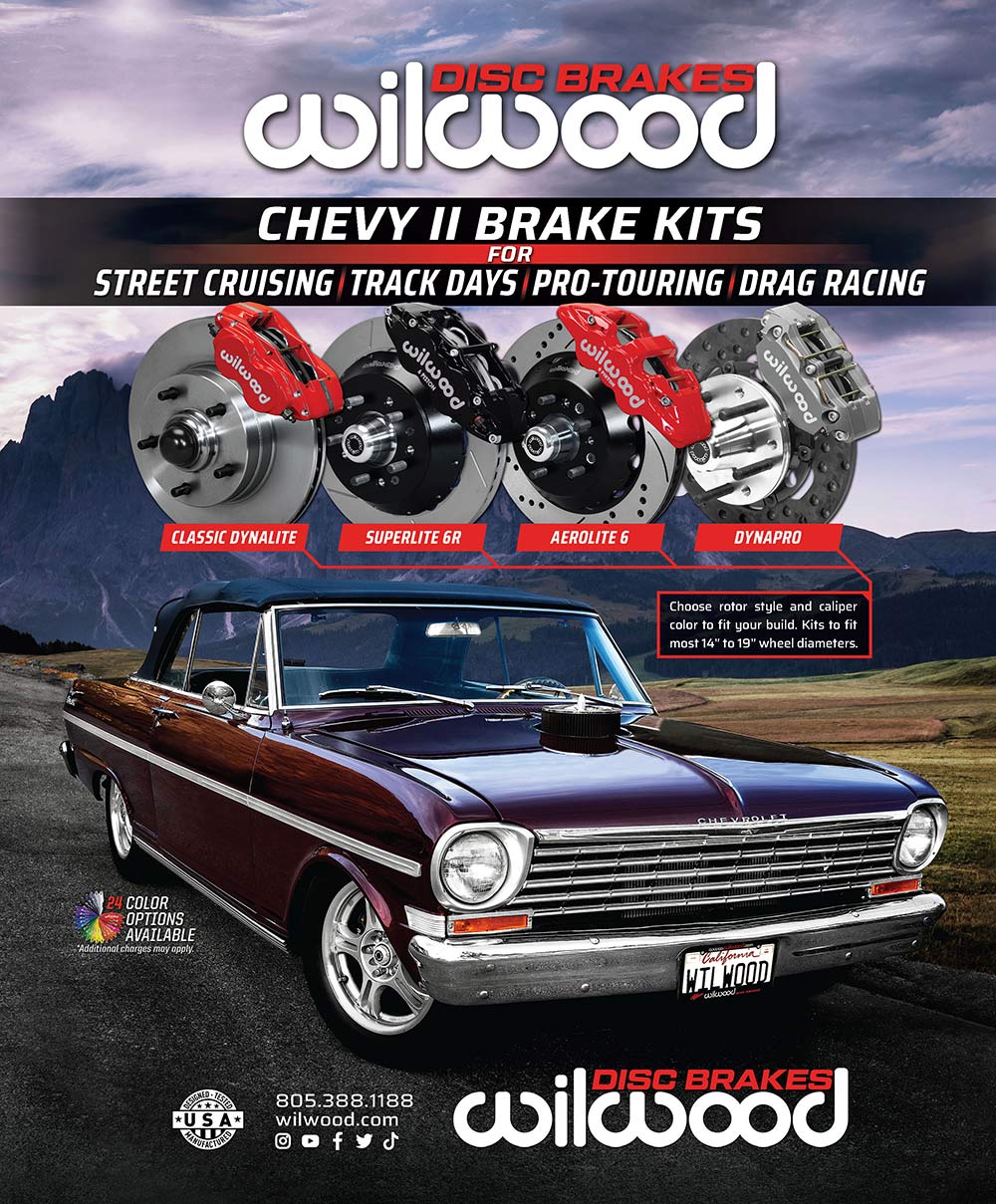

- Wilwood Engineering13

- Year One85

BOWTIE BONEYARD

BOWTIE BONEYARD

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authoreen by many as either a pint-sized Camaro or a grown-up Vega, the Monza was a product of GM’s response to the 1973 OPEC Oil Embargo. When the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries decided to deprive Uncle Sam of oil for mainly political reasons, Americans panicked as the price of gasoline (and all other petroleum-based products, from home-heating oil to plastic spoons) jumped dramatically.

All over America, lightly used SS 396 Chevelles, Z28 Camaros, and virtually every other type of high-performance V-8 machine was rendered nearly worthless. By 1975, tens of thousands of people traded in SS454 Monte Carlos, 409 Impalas, 327 Novas, and the like as partial payment on Honda Civics, Volkswagen Rabbits, Chevy Chevettes, and other compact and subcompact offerings. In most cases, trade-in allowances were well below 20 percent of the new car’s sticker price.

At GM, 1975 brought the Monza (H-body). Offered in coupe, hatchback, and station wagon body styles (all of them two-doors), the Monza was loosely based on the Vega but with many exclusive details. In particular–and of lasting importance to Camaro enthusiasts–the Monza’s rear suspension and rear axle were different than the Vega’s four-link setup.