TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Author

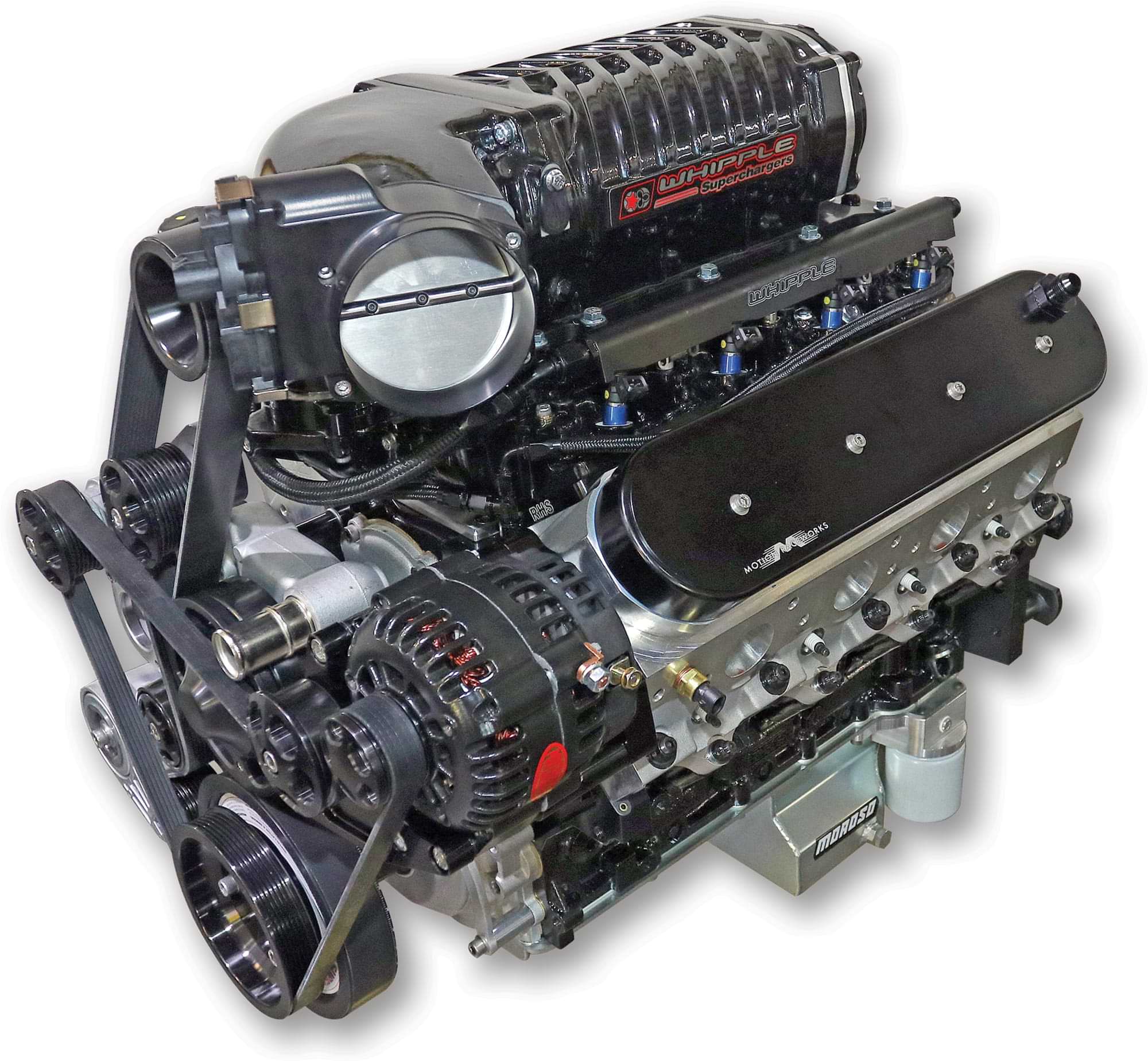

hipple superchargers have been a popular option when it comes to making horsepower for years because their screw-blower designs are proven to make great power in a compact package. A twin-screw supercharger has an advantage over the roots supercharger because its design allows it to move air more efficiently.

The old-school roots supercharger uses the spinning lobes to move air along either side of the case and into the intake plenum. The air exits the supercharger at atmospheric pressure, so boost has to be built up inside the intake plenum.

Meanwhile, a twin-screw supercharger moves air in a cavity created between the screws. As the screws rotate, the cavity moves from the opening in the supercharger case directly to the exit. Meanwhile, the shape of the lobes on the screws also means the cavity gets smaller as the air moves closer to the exit, compressing it. That means the air is already under pressure as soon as it enters the engine.

But that’s not what matters. Here’s what really matters: When comparing a roots supercharger to a twin screw running at the same rpm, the twin screw will almost always provide more boost, provide boost at a cooler temperature, and have less drag on the engine.

Good stuff all around

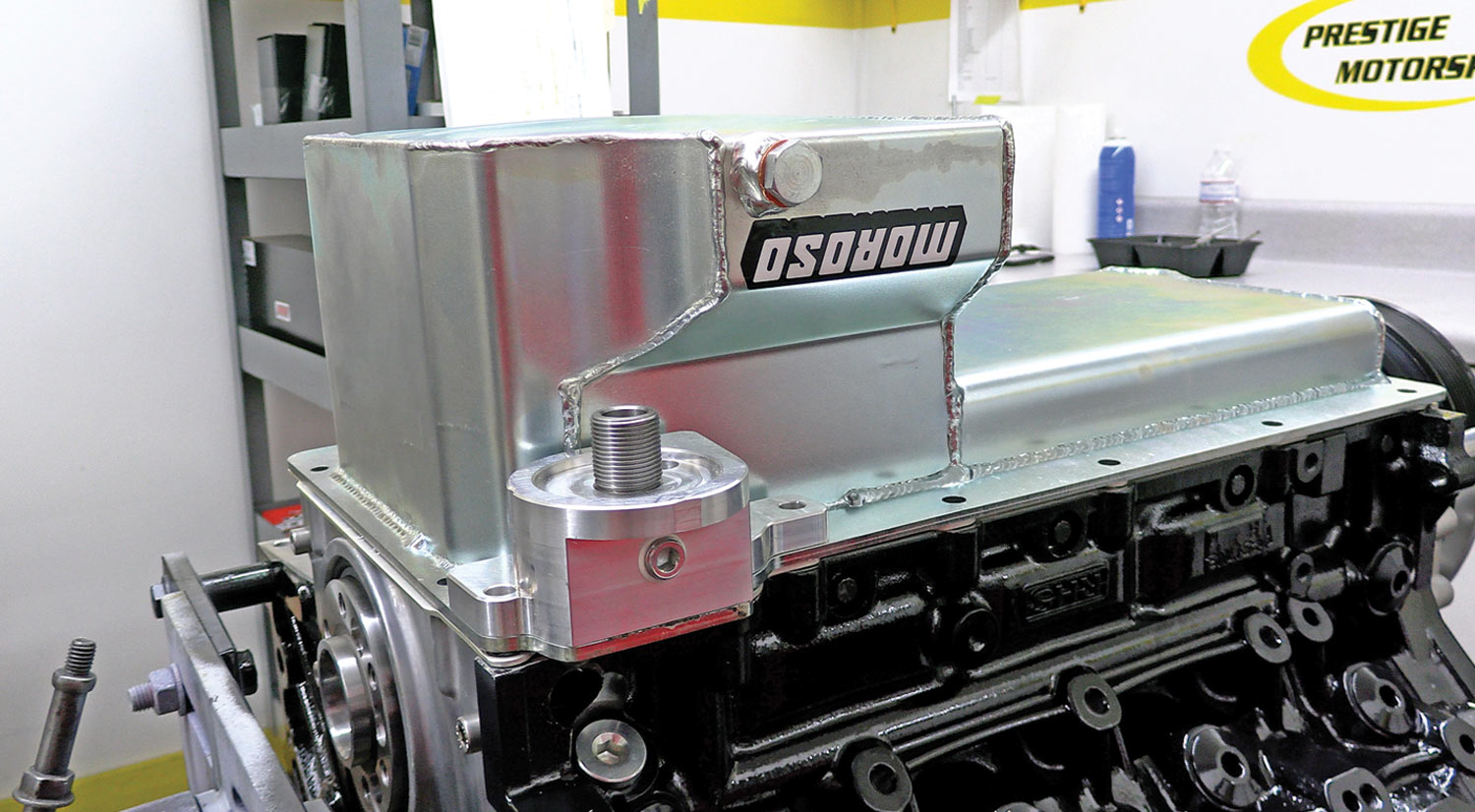

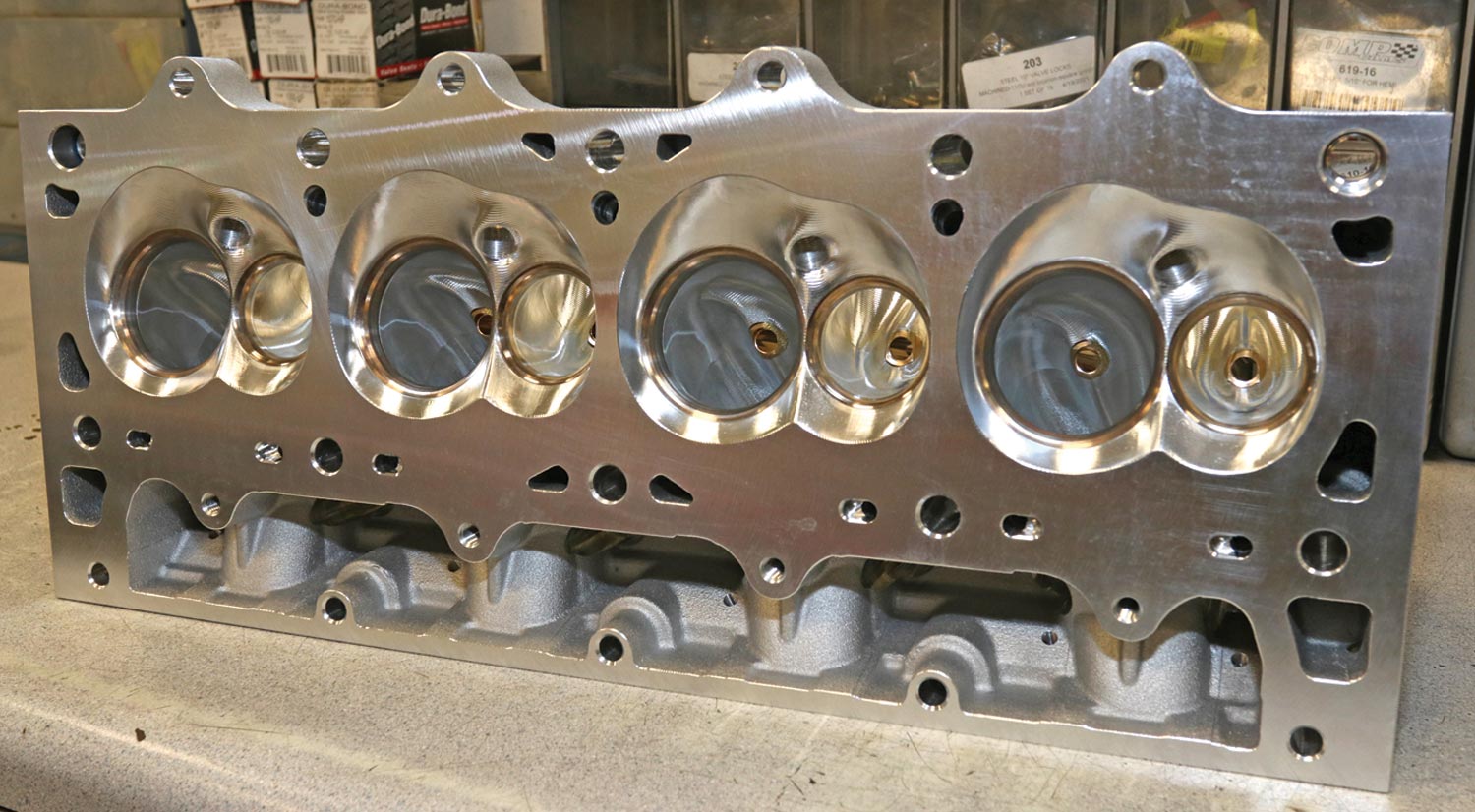

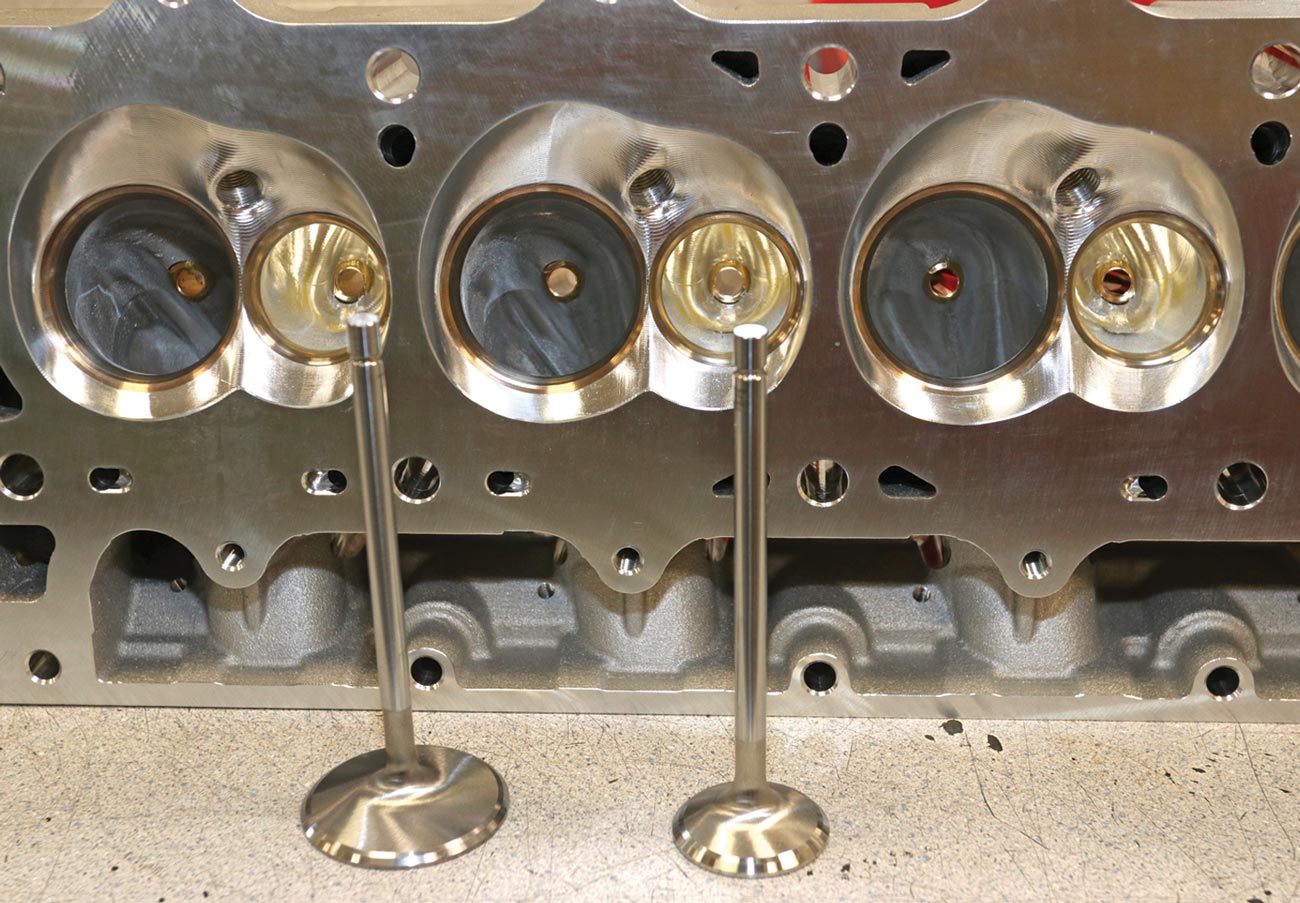

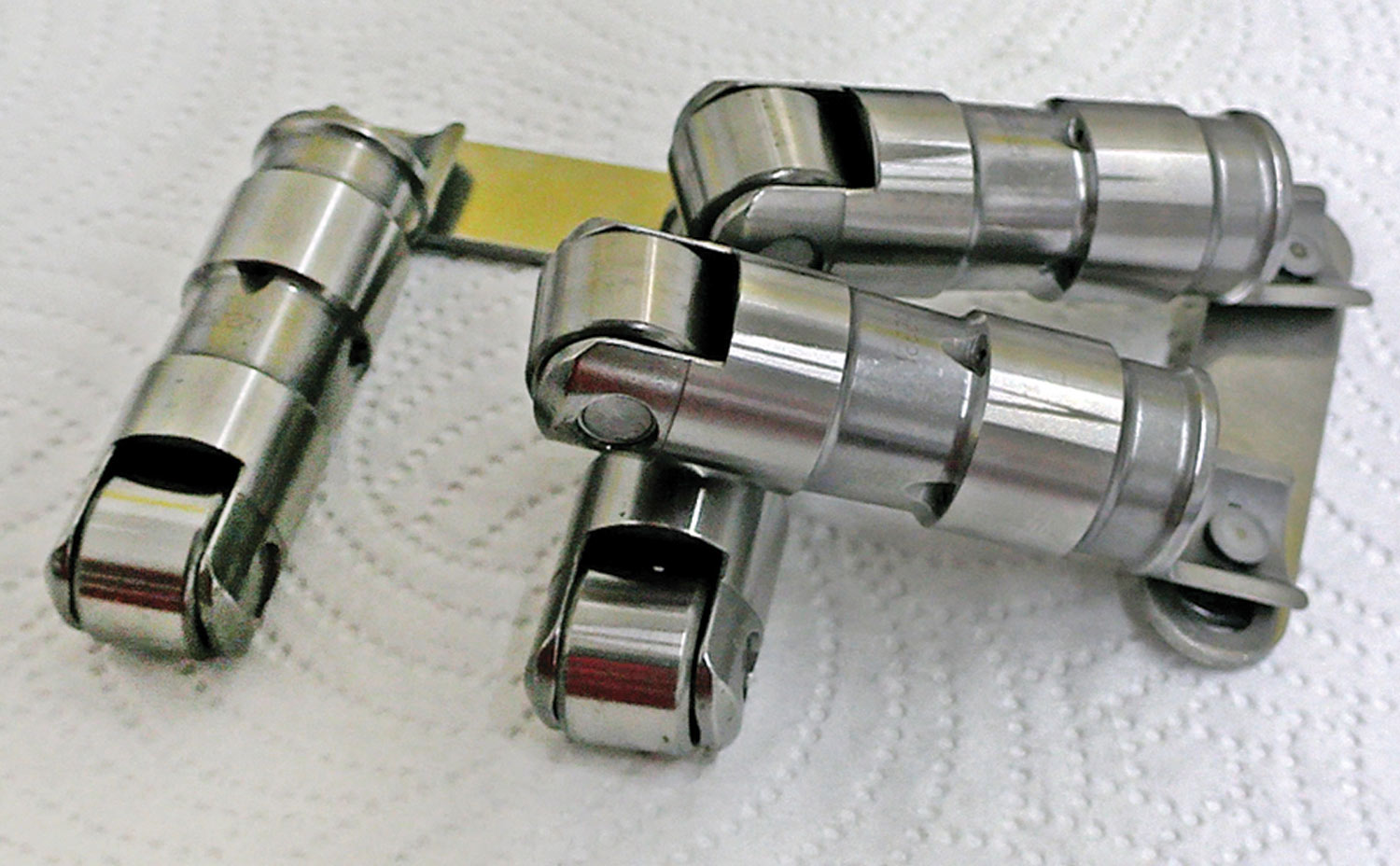

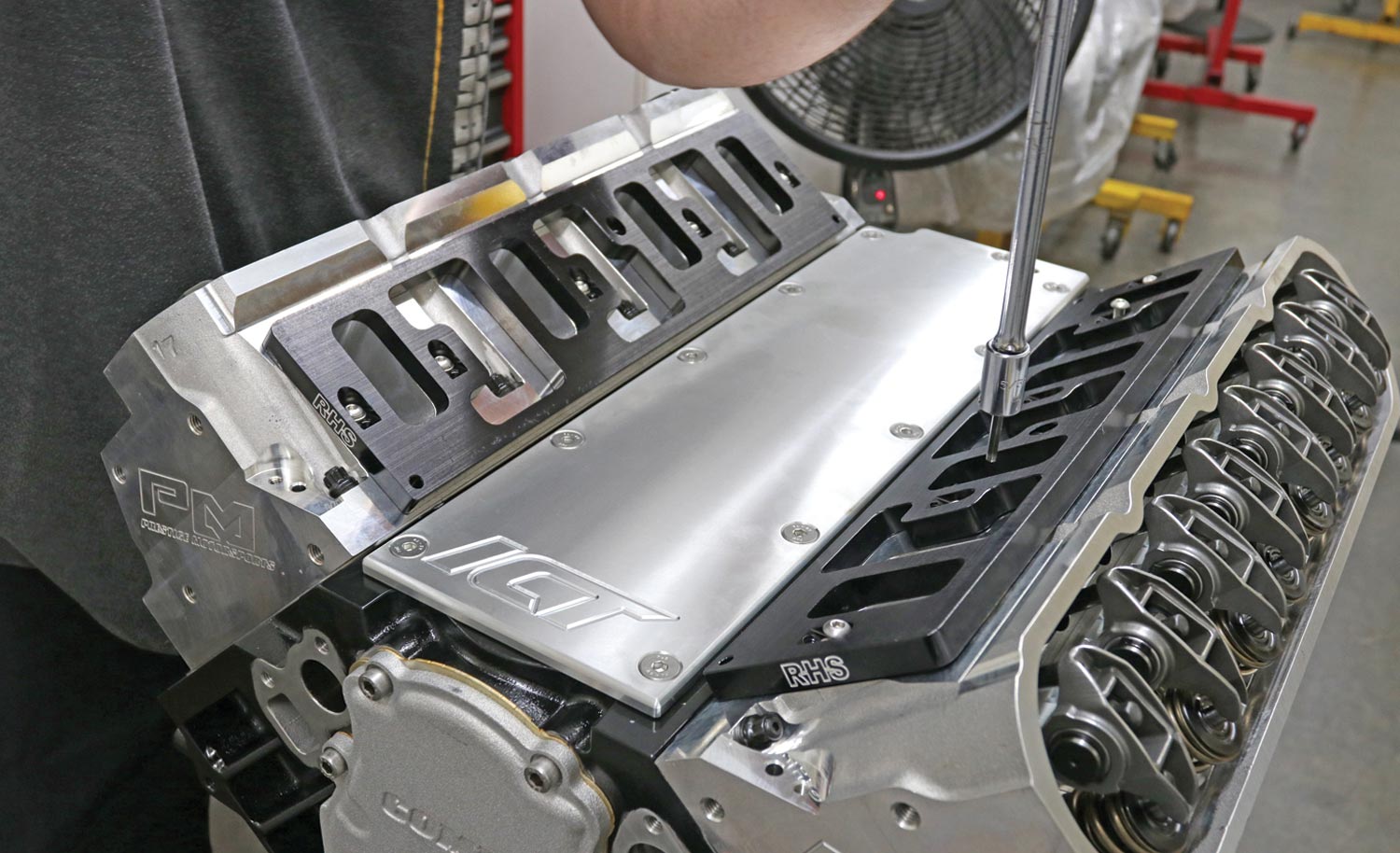

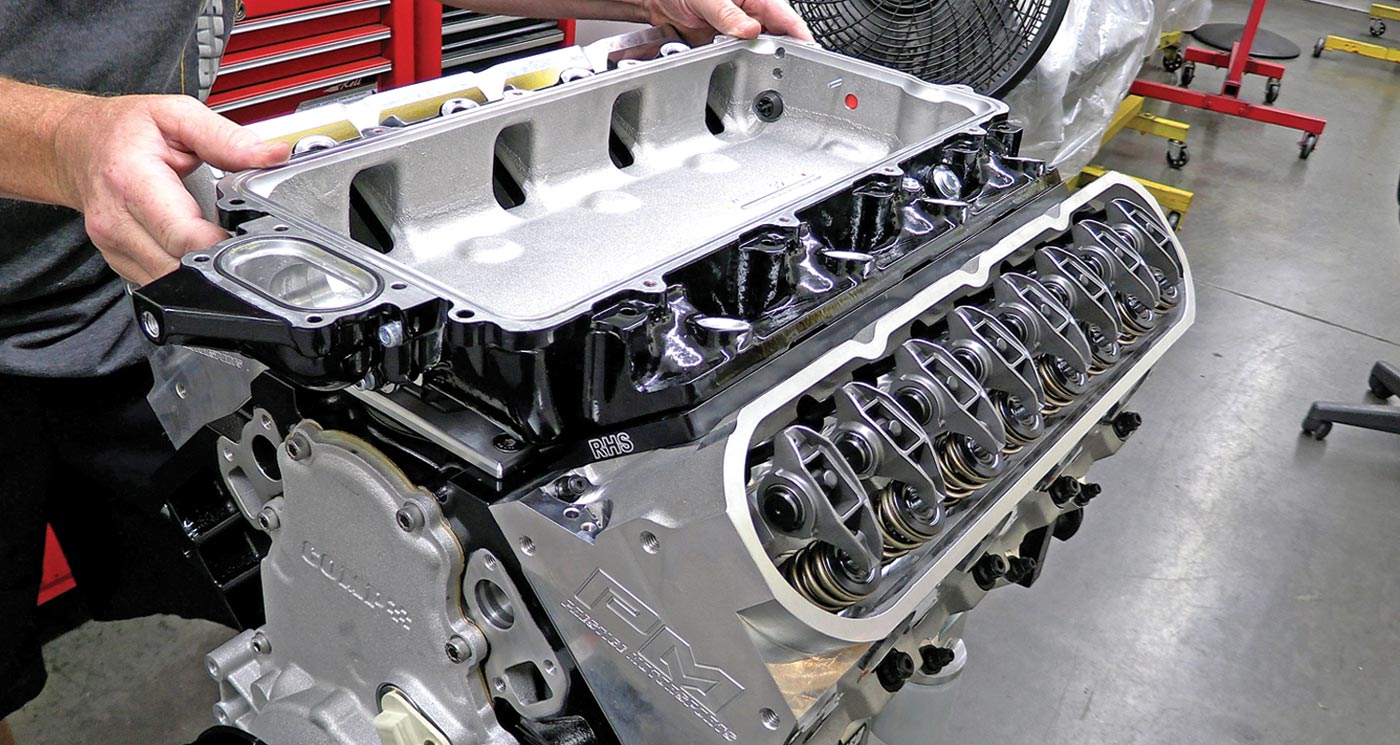

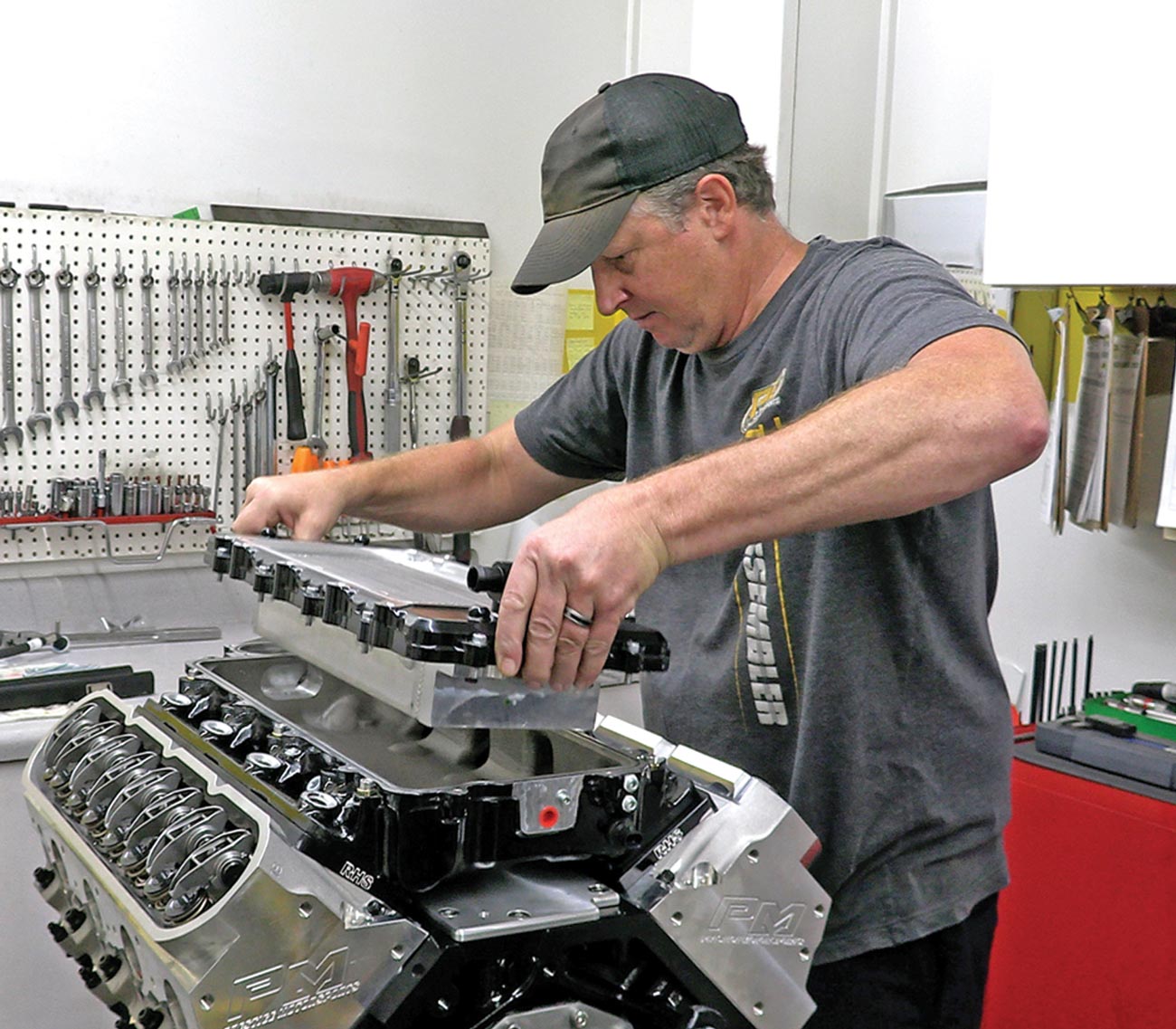

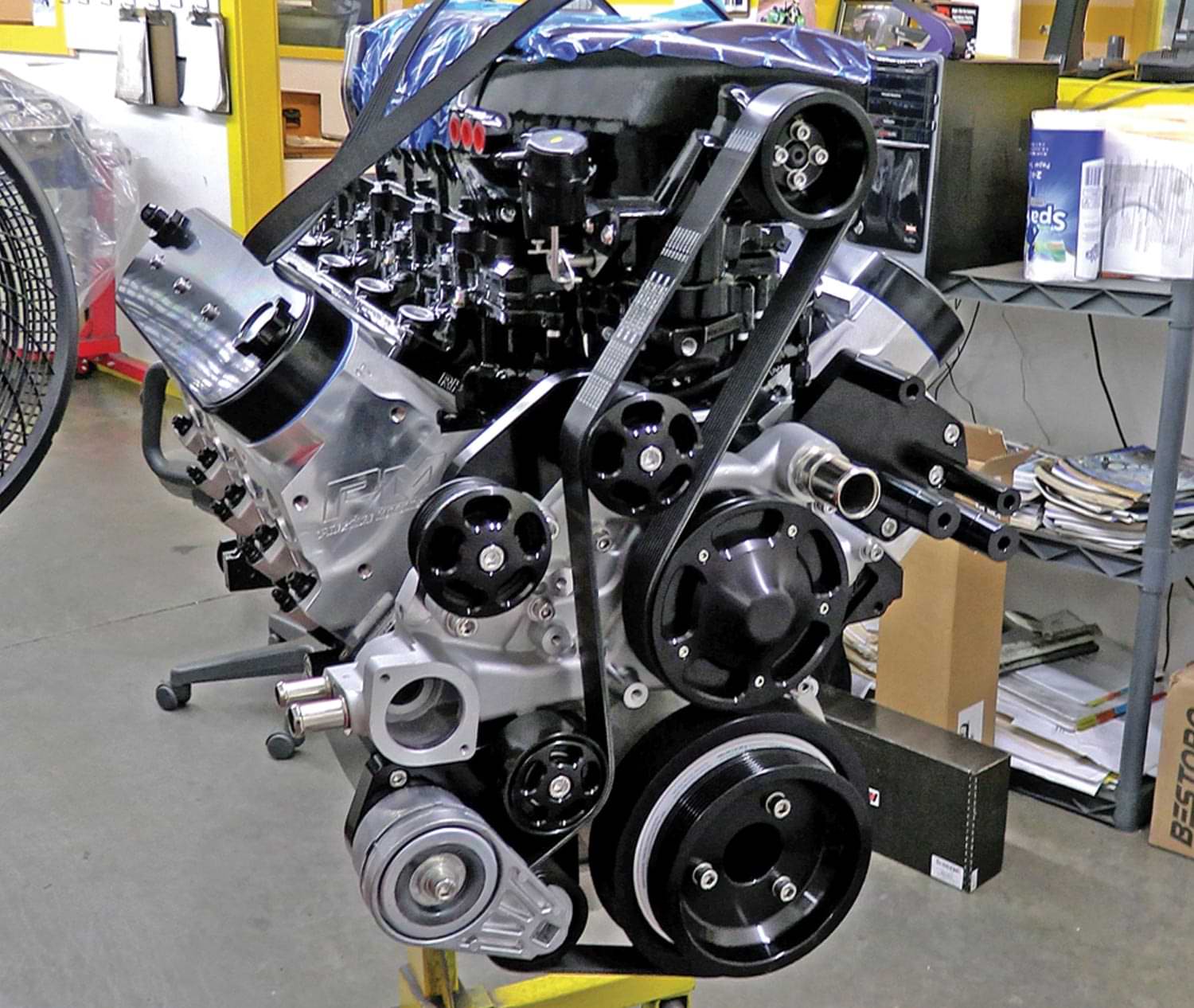

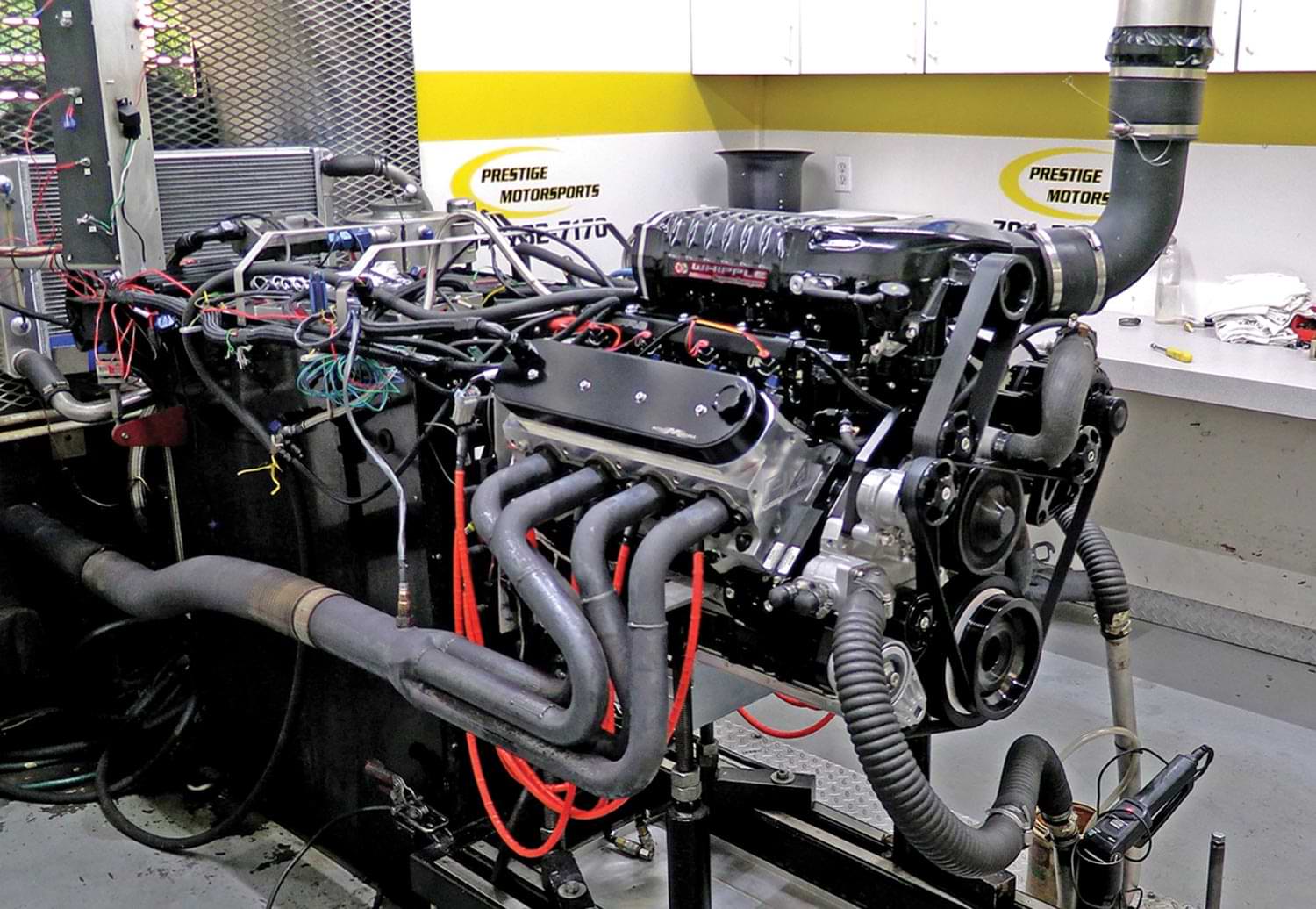

As this went to press, Whipple’s new 3.0L screw-blower was still so new that they didn’t even have any information about it up on their website. But our friends at Prestige Motorsports in Concord, North Carolina, managed to get their hands on one of the first units for a big-inch LS3-based build and they invited us to check out their build featuring one.

Prestige’s engine build is a 454ci LS3 that will be going into a beautiful—and well-built—Pro Street ’69 Camaro. Owner Bryan Lefebvre and his dad have already installed Chris Alston’s Chassisworks suspension, big tubs, and mile-wide rear meats, so it is ready to handle big power. That’s what the big-inch LS and Whipple blower are for.

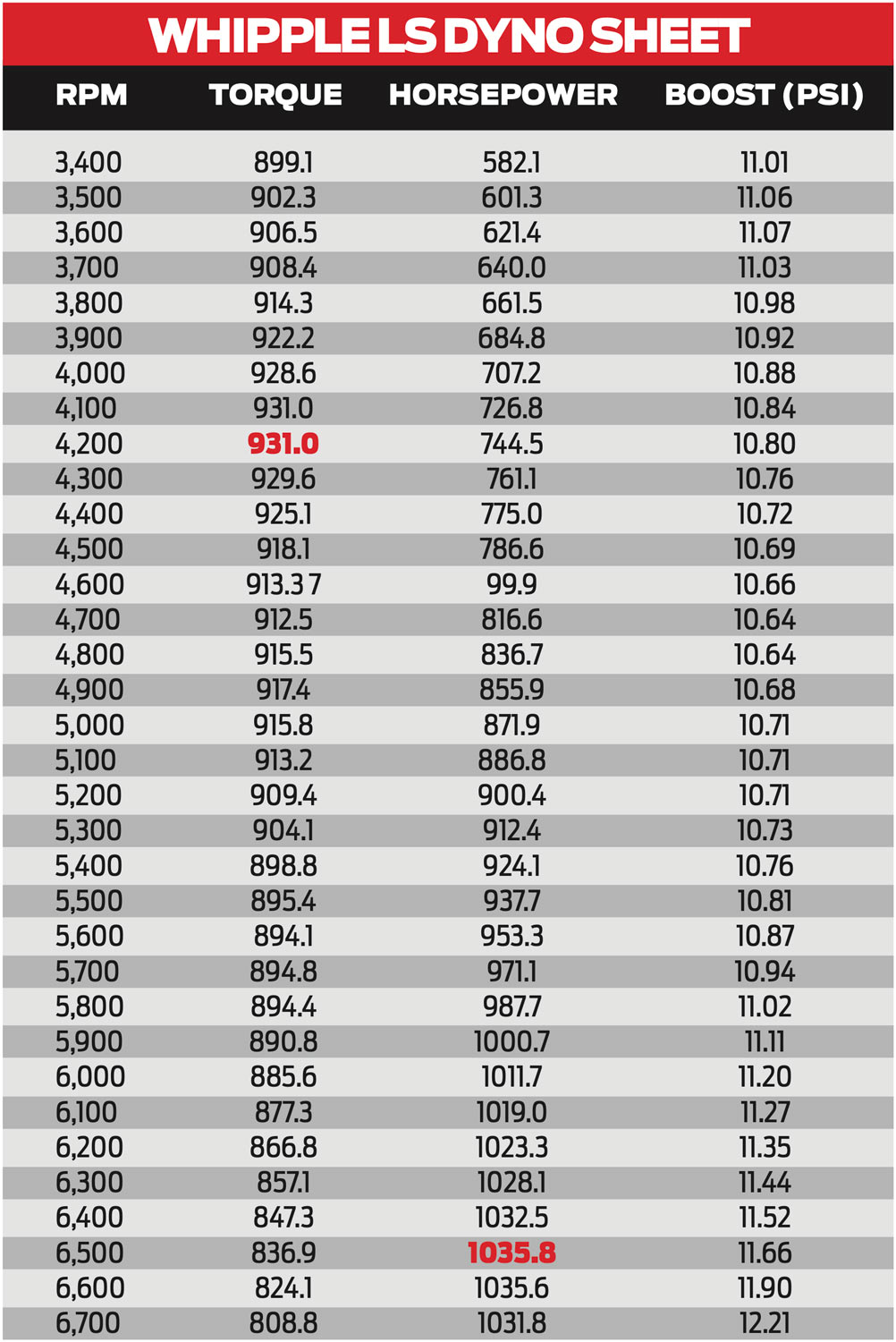

So, let’s quit wasting time. We’ll get onto the build, and best of all, judgment on the overall package with a little dyno time.

SOURCE

SOURCE