Two Trouble-Makin’

Tri-Fives

The Benefits of a Coilover Suspension

Prepping the Block

TOC

TOC

ROB MUNOZ

Wes Allison, Tommy Lee Byrd, Ron Ceridono, Grant Cox, Dominic Damato, Tavis Highlander, Jeff Huneycutt, Barry Kluczyk, Scotty Lachenauer, Jason Lubken, Steve Magnante, Ryan Manson, Jason Matthew, Josh Mishler, Evan Perkins, Richard Prince, Todd Ryden, Jason Scudellari, Jeff Smith, Tim Sutton, and Chuck Vranas – Writers and Photographers

AllChevyPerformance.com

ClassicTruckPerformance.com

ModernRodding.com

InTheGarageMedia.com

subscriptions@inthegaragemedia.com

Mark Dewey National Sales Manager

Patrick Walsh Sales Representative

Travis Weeks Sales Representative

ads@inthegaragemedia.com

inthegaragemedia.com “Online Store”

info@inthegaragemedia.com

Copyright (c) 2021 IN THE GARAGE MEDIA.

PRINTED IN U.S.A

FIRING UP

FIRING UP

BY NICK LICATA

BY NICK LICATA

Such is the case with my 1971 Camaro. It looks and runs great but I’ve been procrastinating on dialing in a few issues because of the fact that it’s 100 percent driveable. But a couple things still need to be addressed. To start with, the side glass is misaligned, so the windows don’t roll all the way up, and they aren’t exactly straight, either. It’s kind of annoying, but I continue to put off doing anything about it. If you’ve ever messed with the window regulators on an early second-gen Camaro, then you know bloody knuckles and a clinched fist of frustration are part of the drill, which is why I’ve been postponing that whole process. I’ve already been in there changing the door locks and have the scars to prove it. It’s just not fun.

A while back I put in a TREMEC Magnum transmission. This meant the trans tunnel had to be cut and massaged here and there to make room for the six-speed to fit. Well, we put the carpet back down and have yet to weld in some sheetmetal necessary to bolt in the shifter boot ring. Lame, I know—and it looks tacky. But it’s another part of the procrastination process that I choose to blame on not having enough time due to my day job (this one) or addressing stuff that needs to be done around the house, instead.

Parts bin

Parts bin By Nick Licata

By Nick Licata

CHEVY CONCEPTS

CHEVY CONCEPTS

@TavisHighlander

@TavisHighlander ![]() TavisHighlander.com

TavisHighlander.com

Vehicle Build by: Big Oak Garage • Hokes Bluff, Alabama

Text and Rendering by Tavis Highlander

Text and Rendering by Tavis Highlander

Text and Rendering by Tavis Highlander

Text and Rendering by Tavis Highlanderven though it has a stock body, this Nomad will be all sorts of wild in many aspects. The first thing to hit your eyes will be the two-tone black and root beer flipping to copper paintjob. Wheel centers and some bits of trim will be treated to some Axalta paint in addition to the main body. Once your eyes process the slick paint, you’ll see the aired-out stance that almost puts the rockers on the ground. RideTech components combined with an Art Morrison Enterprises chassis accomplish the tasks of handling at ride height and looking good while parked.

Backing up all the appearance items is a stout drivetrain. There’s an LT5 crate engine barking out its 755hp exhaust note through a Borla exhaust. Backing up the LT5 is a 10L90-E 10-speed automatic transmission. Combine all this with the craftsmanship of Big Oak Garage and you’ve got one incredible Nomad ready for the show circuit as well as the street.

FEATURE

FEATURE Photography by Wes Allison

Photography by Wes Allison

That’s how Jason Blain describes his 1968 Camaro when his dad brought it home from a Jonesboro, Arkansas, used car lot back in 1987. “My dad paid $2,650 for the car, which was actually in decent shape,” Jason recalls. “The body wasn’t perfect, but there were no major issues and the car actually ran OK. The paint was passable, and if you looked close enough in certain areas, you could see the original Rally Green paint and some sort of red color underneath that.”

TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

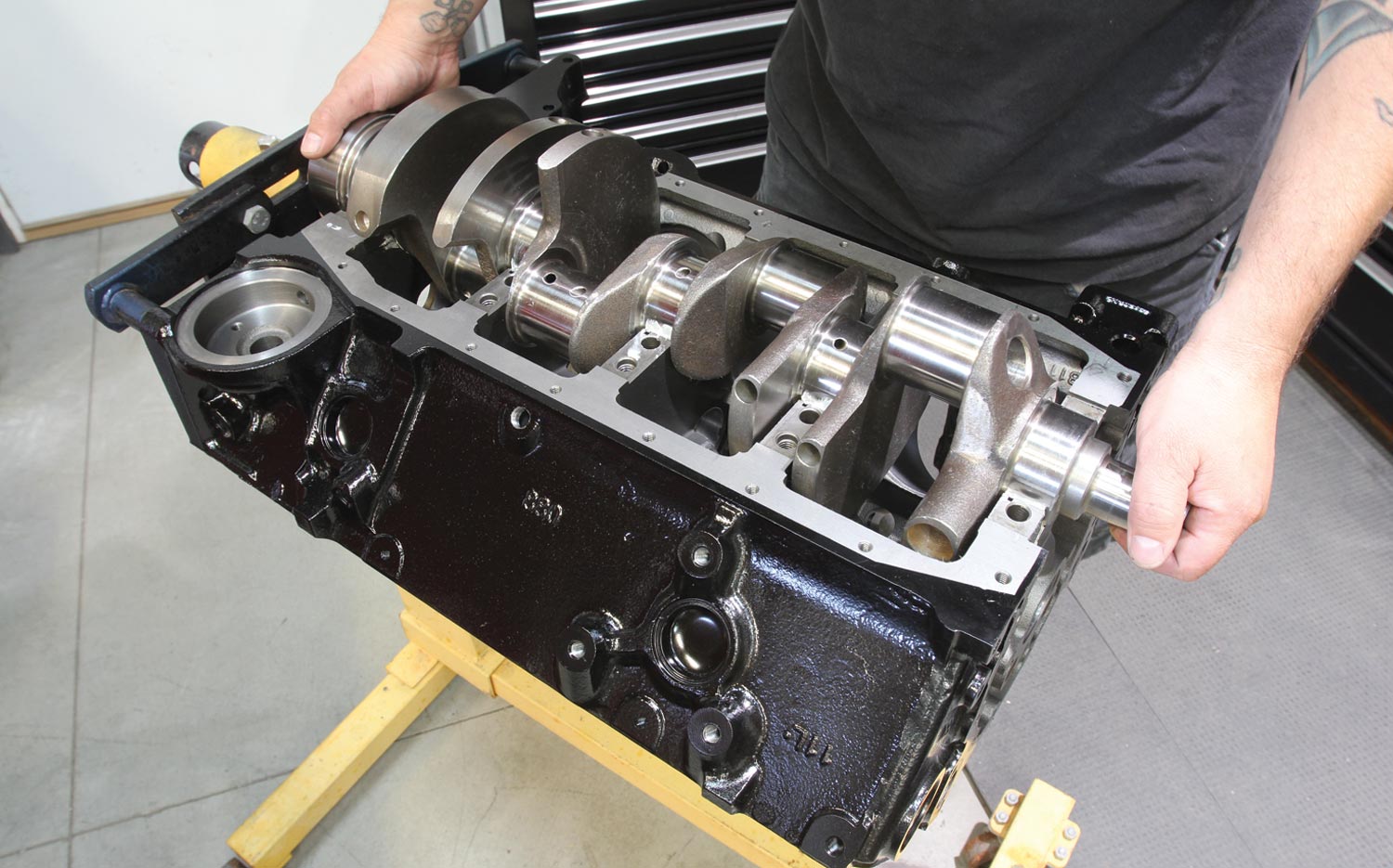

Photography by The Authorith the propagation of crate engines over the last 30 or so years, it’s hard to believe that anyone would bother building a mild street engine from the ground up. Yet here we are, doing exactly that. Why, you may ask? Simply put, we find it to be both rewarding and challenging—two traits not typically associated with a crate engine build (unless you count the unboxing portion!). For those of us wealthy in the time department, taking a couple days (OK, weeks) to build an engine might make sense. Those of us with only a couple hours a week to spare on our project might look at the crate option with a little more regard. Either way, there is no wrong or right, just what works for you.

Something that has gained in popularity thanks to suppliers like Summit Racing stocking a myriad of options is to build an engine from the ground up using an aftermarket block, machined and ready to go. We’ve done a couple builds in the past based around these blocks with great results. Machined to a finished bore, these blocks can be mated with turnkey components without any further machine work.

During a recent conversation with our buddy Zane Cullen at Cotati Speed Shop, the discussion turned to the built-not-bought crate engine topic. We both agreed that in a shop setting, it makes perfect sense to drop a crate engine in a project vehicle when time and labor is such a precious commodity. But given the opportunity, it would be fun to build an engine from the ground up, selecting the components and fitting things together. It was decided to shift gears on one of his current projects, setting aside the GM 350/350 crate engine he’d procured, instead having us build a stroked 350 based on a Chevrolet Performance bare engine block and components from Summit Racing, with the purpose being a budget-friendly, naturally aspirated, mild street engine, in the 400hp neighborhood, similar to that 350/350 combo that Cullen had his eye on originally.

FEATURE

FEATURE Photography BY The Author

Photography BY The Author

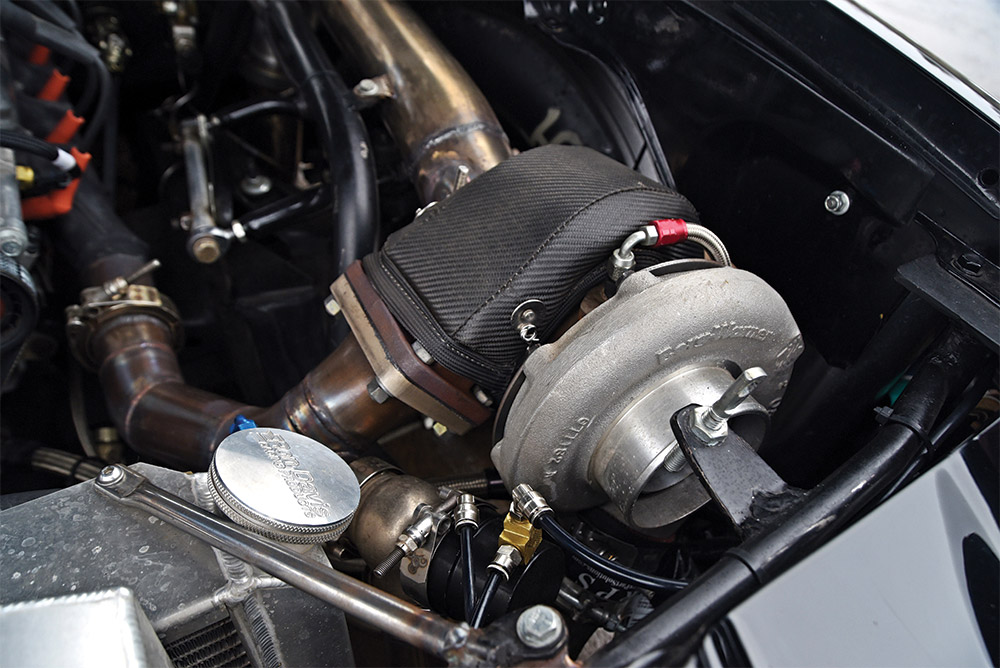

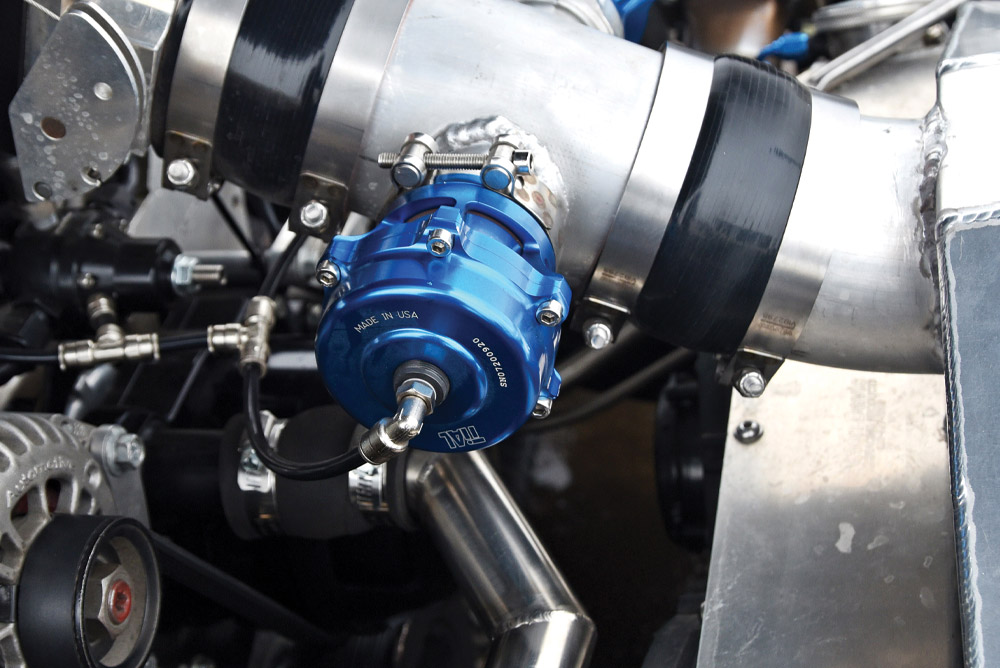

ome married couples work out together, some take cooking courses, and some enjoy wine tasting at the local country club. But for Justin and Jenny Moses of Braselton, Georgia, marital bliss comes in the form of a screaming Chevrolet engine and a four-speed manual transmission. The couple campaigns two cars in the Southeast Gassers Association, which is a growing organization that focuses on reliving the glory days of drag racing with period-correct, heads-up racing. With authentic pound-per-cubic-inch classifications and a very strict rules package that applies to both the appearance and performance of the vehicles, this group races hard and thrills spectators all over the Southeast.

With wild paint schemes, and even wilder antics on the track, the two cars might seem like the stars of their racing program, but Justin and Jenny are the real highlights, always providing a helping hand or a good laugh when fellow competitors need it most. The camaraderie and fellowship within the Southeast Gassers Association is second to none, and that’s why it’s one of the fastest-growing organizations in all of drag racing. Justin and Jenny became involved in this gasser group nearly 10 years ago, and their racing crew includes family and friends who pitch in to keep the operation rolling from race to race.

TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author and General Motors

Photography by The Author and General Motorsard as it is to believe, we’re quickly approaching the 25th anniversary of the LS engine and the cultural phenomenon it established within the automotive world.

It started with the 5.7L LS1, but the architecture expanded to include a range of displacements, from 4.8L (293 ci) to 7.0L (427 ci). Most of the variants were used in trucks, with some featuring E85 capability and cylinder-deactivation technology. All told, there were more than two dozen production versions, along with even more crate engine options from Chevrolet Performance—including those built with the racing-bred, cast-iron LSX Bowtie Block.

From the lowest-output base truck engine to the supercharged LS9, each shared the core design elements that made the LS a revolution when new and continue to prove its relevancy two-and-a-half decades later. It’s been an admirably robust and durable engine, but more importantly, its capability to process air greatly expanded its performance range. It makes good torque in truck applications, but from a high-performance standpoint the LS’s airflow capability enables it to rev like no other pushrod engine before it, giving more complex multi-cam engines a run for their money on the dyno.

FEATURE

FEATURE

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authoratt Cirocco, of Massapequa, New York, found himself with a daunting dilemma on his hands. “I found out about a good builder 1972 Chevelle for sale locally. When I got there I saw an equally cool 1969 Camaro the seller was willing to unload.” After much deliberation, a decision was made to grab the Chevelle for his new project. You never know how lady luck is going to treat you on any given day, but luckily for this guy he slept well knowing he made the right choice that day.

TECH

TECH Photography by The Author and John Baechtel/Hot Rod Engine Tech

Photography by The Author and John Baechtel/Hot Rod Engine Techhe big-block Chevy as we know it today was big news in 1965. The Corvette and fullsize cars debuted a replacement for the antiquated 343/409 W engines with some ancestral connections, like the crankshaft. But for the techno-engine geeks, the Rat was noteworthy for the odd valve angle cylinder heads. The 427 and its smaller-inch brother 396 both sported a set of “porcupine” heads, no-doubt offered by some journalist who made the connection between the big-block’s bizarre valve angles and that rodent with its protruding quills.

If you didn’t catch our Part I story on small-block valve angles (July ’21 issue), we’ll step back a moment to define our use of the term valve angle. This is a valve angle measured in degrees that references off of the centerline of the cylinder bore. So if we were to measure the angle of an OE big-block iron or aluminum head, we’d see there is a 26-degree angle to the intake valve from the bore centerline reference point. The stock exhaust angle is a much more vertical 17 degrees. Both valves are canted by 4 degrees in opposite directions.

Oddly, you would think that the big-block might have benefited from additional research and perhaps have utilized a taller intake valve angle, but in fact that angle is actually greater than the small-block 26 degrees versus the small-block’s 23 degrees, but the Rat sports a 4-degree tilt of both the intake and exhaust valves. In a typical wedge combustion chamber cylinder head like the small-block Chevy, the valves are arranged in a single file. But big-block cylinder head designers departed from that concept by tilting the intake valve 4 degrees toward the center of the cylinder. Actually, both the intake and exhaust valves are tilted 4 degrees but in opposite directions to enhance flow.

he big-block Chevy as we know it today was big news in 1965. The Corvette and fullsize cars debuted a replacement for the antiquated 343/409 W engines with some ancestral connections, like the crankshaft. But for the techno-engine geeks, the Rat was noteworthy for the odd valve angle cylinder heads. The 427 and its smaller-inch brother 396 both sported a set of “porcupine” heads, no-doubt offered by some journalist who made the connection between the big-block’s bizarre valve angles and that rodent with its protruding quills.

If you didn’t catch our Part I story on small-block valve angles (July ’21 issue), we’ll step back a moment to define our use of the term valve angle. This is a valve angle measured in degrees that references off of the centerline of the cylinder bore. So if we were to measure the angle of an OE big-block iron or aluminum head, we’d see there is a 26-degree angle to the intake valve from the bore centerline reference point. The stock exhaust angle is a much more vertical 17 degrees. Both valves are canted by 4 degrees in opposite directions.

Oddly, you would think that the big-block might have benefited from additional research and perhaps have utilized a taller intake valve angle, but in fact that angle is actually greater than the small-block 26 degrees versus the small-block’s 23 degrees, but the Rat sports a 4-degree tilt of both the intake and exhaust valves. In a typical wedge combustion chamber cylinder head like the small-block Chevy, the valves are arranged in a single file. But big-block cylinder head designers departed from that concept by tilting the intake valve 4 degrees toward the center of the cylinder. Actually, both the intake and exhaust valves are tilted 4 degrees but in opposite directions to enhance flow.

FEATURE

FEATURE

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorn a time of national pandemic, most of our hobby’s typical car shows, cruise-ins, and get-togethers have been canceled or postponed. Thus, finding new and interesting rides to brag about in this here magazine has become a little more difficult. However, we here at All Chevy Performance have learned to adapt to these trying times and some of us (including myself) have earnestly taken to the world of social media to find our next big feature car.

TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorot rodding is a complicated, nuanced hobby, but part of its appeal is its science. Bench racing new techniques and analyzing successes and failures make it exciting. The car community is filled with us nerds trying to find our cars’ hidden, untapped potentials.

Suspension is the occasionally overlooked area that can garner huge improvements with your worn-out muscle car, and coilovers are a modern solution to vintage problems. They replace heavy springs and shocks with a package that’s easy to install, tune, and is significantly lighter. They can make drastic changes to your car’s driving characteristics.

Coilovers are a nicely packaged piece of performance goodness, but what should you consider when purchasing, how do you adjust them, and what are their differences? We break it down from a hot-rodding perspective—a degree in fluid dynamics not necessary.

TECH

TECH

VIDEOGRAPHY BY Ryan Foss Productions

VIDEOGRAPHY BY Ryan Foss Productionsuring the ’60s Chevrolet had endured a barrage of negative publicity surrounding the Corvair (primarily due to Ralph Nader and his book Unsafe At Any Speed), but their reputation would soon be salvaged as they had decided to enter the ponycar wars. The all-new Camaro was introduced in September of 1966 to compete with Ford’s Mustang that had been introduced in April of 1964, and the 1964 Plymouth Barracuda, which debuted roughly two weeks earlier than Ford’s new offering.

The first-generation of Camaros were produced for the 1967-1969 model years and were based on GM’s F-body, rear-wheel-drive platform. For the 1967-1968 model year, the sheetmetal was unchanged, for the most part, but there were a few minor exceptions. The most obvious differences for 1968 were the new front and rear marker lights and the elimination of vent windows in the doors. Then, in 1969, a new body was introduced that looked longer and lower but still retained the appeal that had made the Camaro such a success.

While all Camaros are popular, the first-gen series remained one of the most sought-after cars in the ranks of Chevrolet fans, and every once in a while a solid original example is discovered like the one we have here. This 1969 coupe came from Texas where it had been sitting in a private collection for what was estimated to be 10-15 years. The owner didn’t know much about the car, but the body was surprisingly nice, the engine had a fresh coat of paint, but its condition was unknown (the owner couldn’t verify if it had been rebuilt) and there were a few new parts, like the A/C compressor and hoses.

BOWTIE BONEYARD

BOWTIE BONEYARD

Photography BY The Author

Photography BY The Authorn 1969, Chevrolet built and sold 243,085 Camaros. It was the final year for the first-generation (1967-1969) of GM’s reply to the Ford Mustang–inspired ponycar craze. While any Camaro today is prized, adored, and kept in pristine condition as a favorite toy and investment (in equal parts), it wasn’t always that way.

This writer was hatched in 1964 and though not old enough to have driven first-gen Camaros as new cars, I painfully recall being 10 years old and seeing fleets of rusty, crusty, neglected Camaros rattling along the New England streets of my youth. Thanks (?) to the prodigious amount of road salt used in the wintertime, even GM’s best zinc-chromate body dip was no match for the dreaded tin worm. By 1974, Camaros that saw year-round use displayed deep scars and gashes. My then 10-year-old mind watched countless Camaros wither into dust.

In this sampling, let’s explore a pair of 1969s that succumbed to the rust monster but somehow managed to hold on as relics of bygone days. In both cases, their owners “have plans” but since brand-new 1969 Camaro body shells are readily available from Dynacorn and similar outfits, perhaps the best route might be to let them sit as warnings to never, ever expose your favorite car to the hazards of road salt!

Advertiser

- ACES Fuel Injection89

- American Autowire7

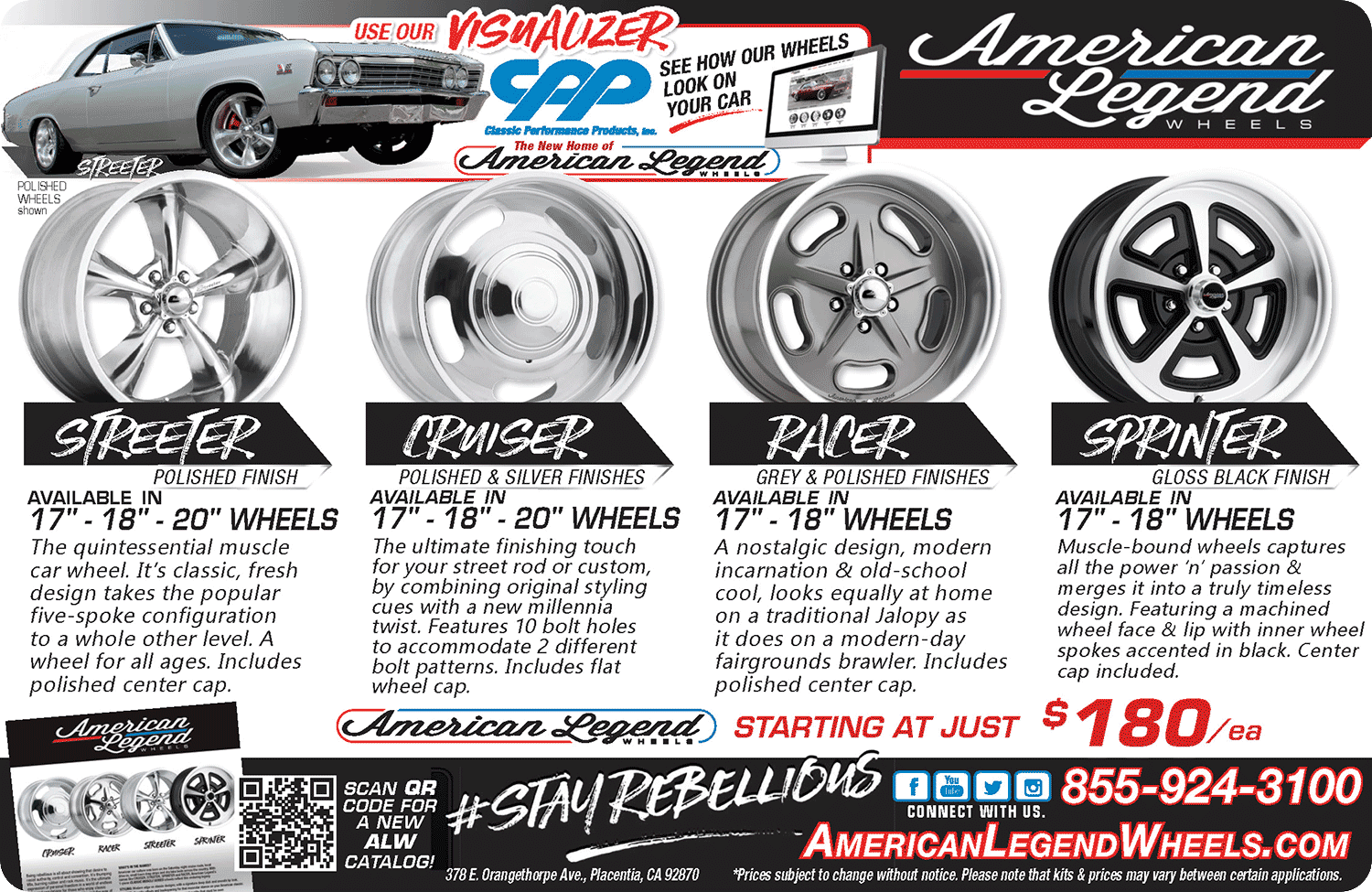

- American Legend Wheels65

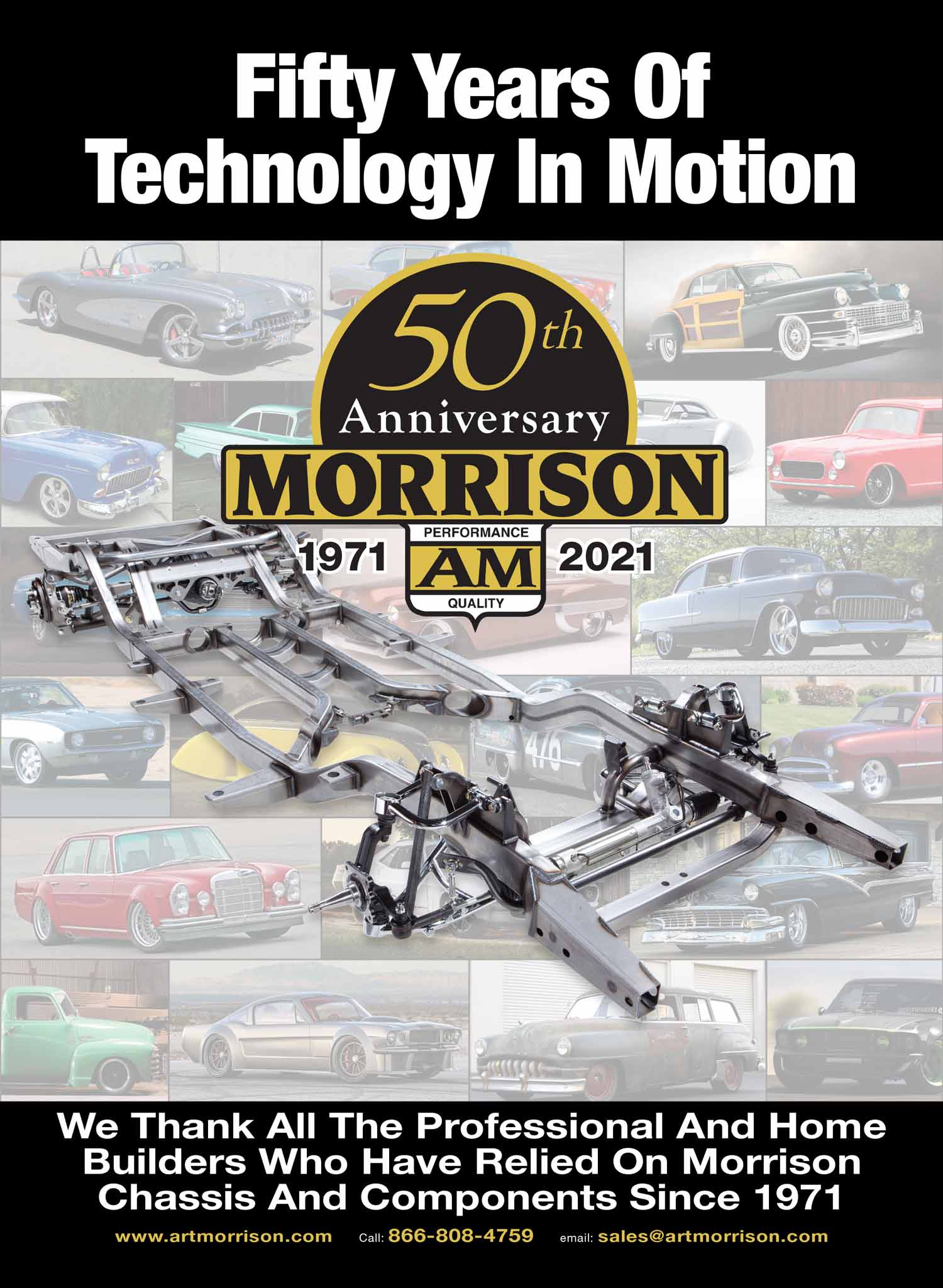

- Art Morrison Enterprises39

- Auto Metal Direct49

- Borgeson Universal Co.51

- Bowler Performance Transmissions85

- Classic Industries41

- Classic Instruments9

- Classic Performance Products4-5, 85, 92

- Concept One Pulley Systems85

- Dakota Digital91

- Danchuk USA13

- Duralast29

- FiTech EFI75

- Gandrud Chevrolet77

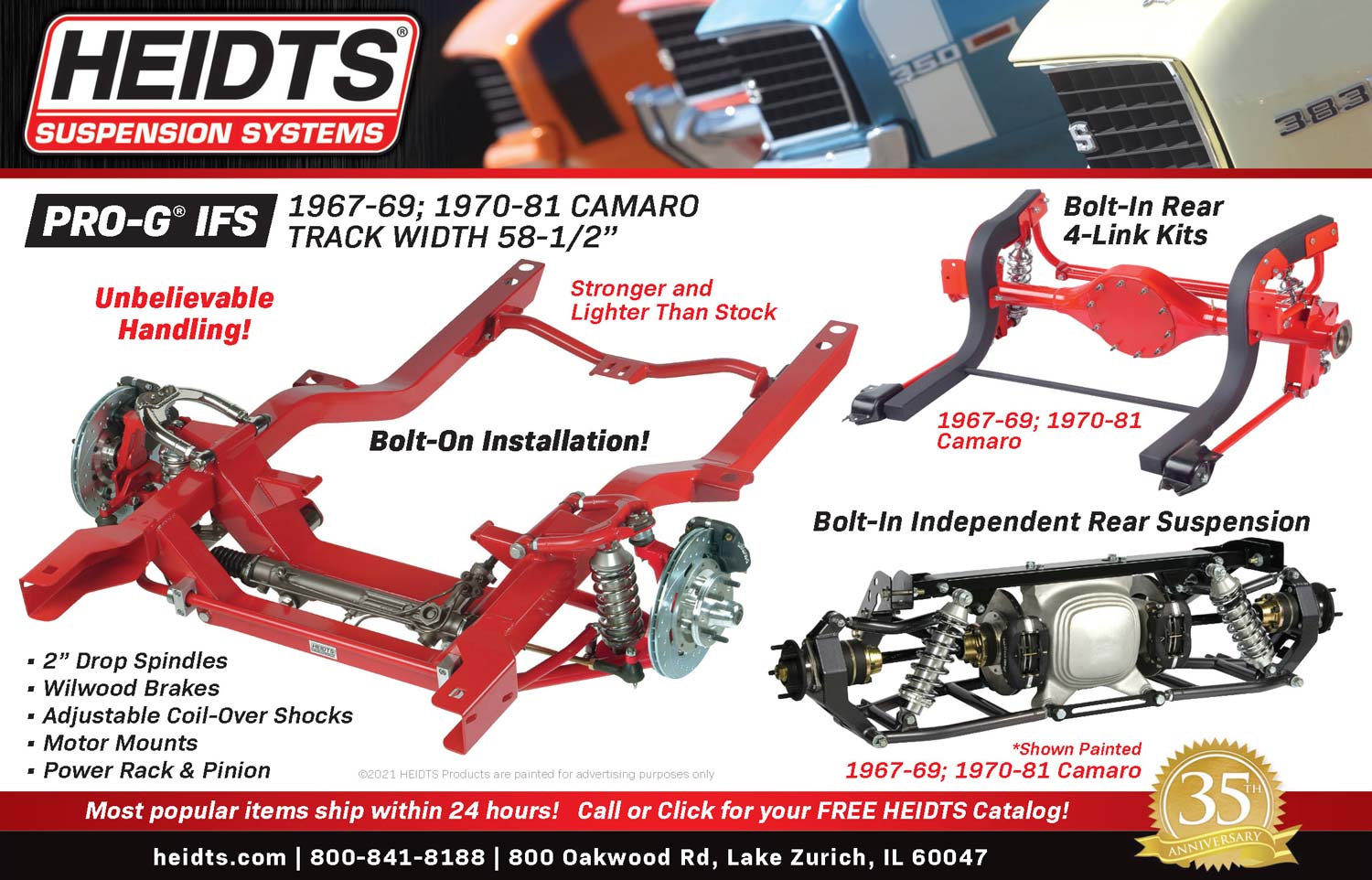

- Heidts Suspension Systems65

- HushMat89

- John’s Industries89

- Lokar2

- National Street Rod Association63

- Optima Batteries11

- Original Parts Group85

- Performance Online27

- Roadster Shop47

- Scott’s Hotrods77

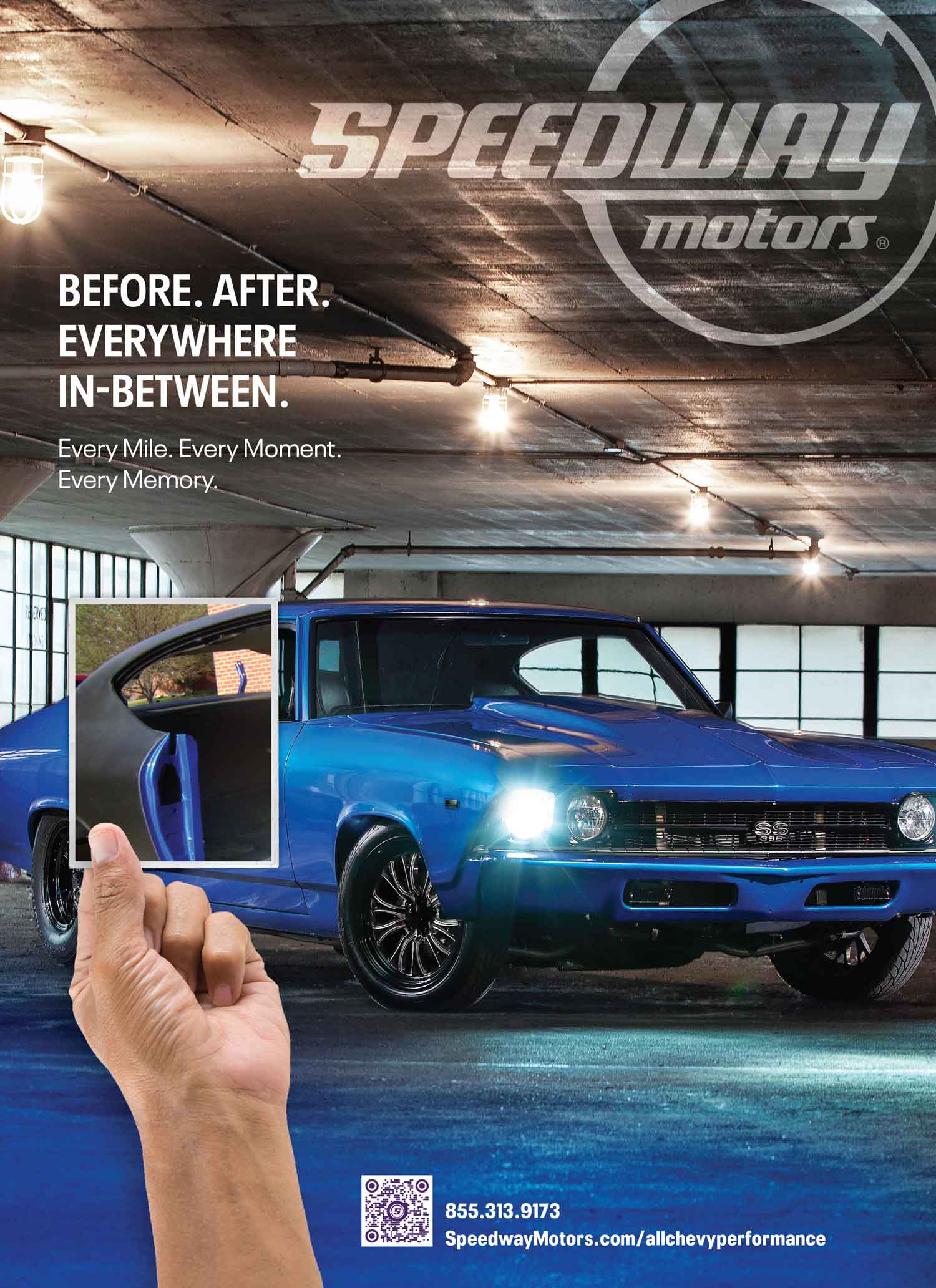

- Speedway Motors61

- Tuff Stuff Performance Accessories75

- Vintage Air6

- Wilwood Engineering43

- Year One77