TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Author

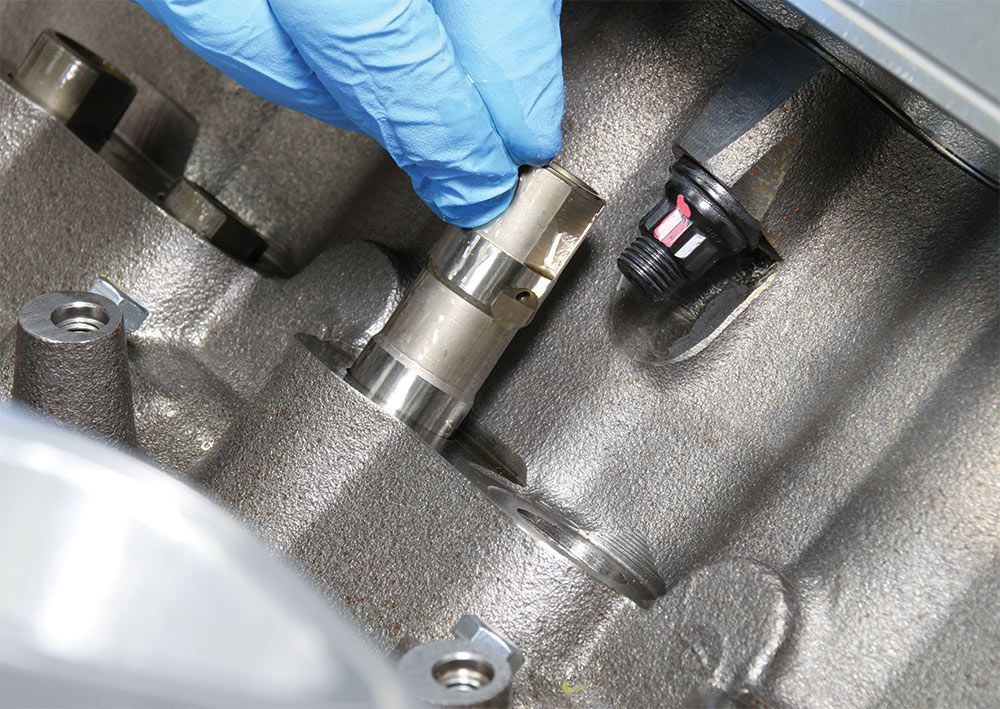

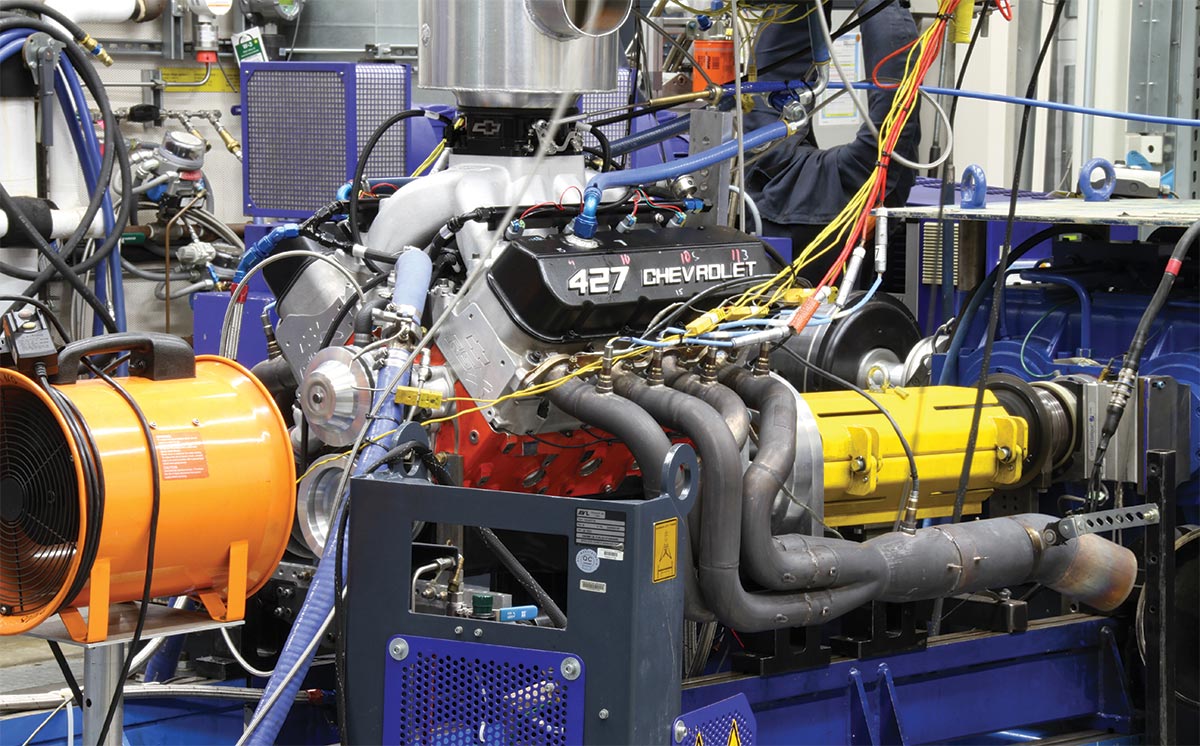

e’re back with the final installment of building Chevrolet Performance’s all-new, 1,004hp ZZ632 crate engine. Previously, we detailed the short-block buildup, including the installation of its hydraulic roller camshaft.

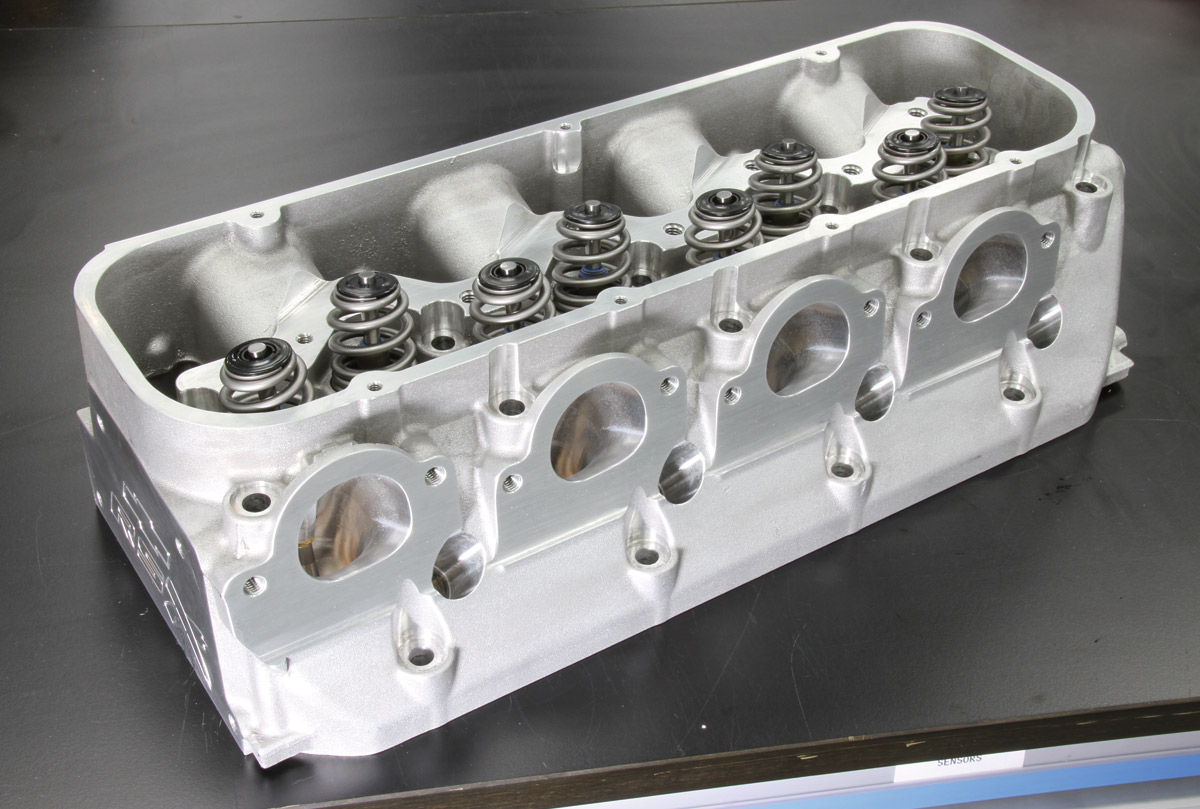

Focus now moves to the top end of the electronically controlled, port-injected, crank-triggered monster big-block, starting with the heads. For that step forward with our story, however, we need to step back in time to the mid ’80s.

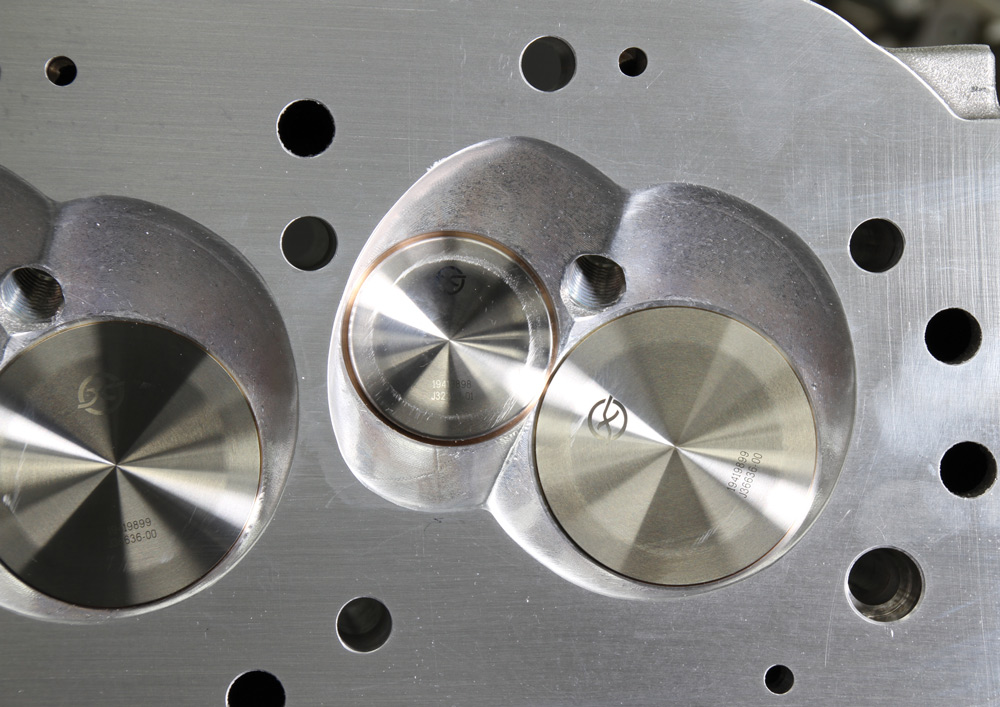

That’s when GM engineer Ron Sperry pushed up the sleeves on his Members Only jacket and got to work on a unique spread-port, straight-flow cylinder head that was intended for the Pro Stock wars. The design was a winner, with off-the-chart airflow capabilities, but by the time the first few sets of heads were cast and offered to racers, in 1988, NHRA had changed the class rules and Sperry’s head was effectively dead.

Yes, the head was offered in the performance parts catalog for a while but it faded away in the early ’90s, like a set of fuchsia heartbeat stripes on the rear window of a Beretta. But time didn’t change the viability of his design.

In the approximately 35 years since Sperry developed his distinctive spread-port design, plenty of big-block cylinder heads have come and gone, but almost all of them have featured variations on the conventional port layout, regardless of whether they were oval- or rectangular-port designs. A great many of them, through the sheer volume of their ports, worked very well at processing tremendous amounts of air.

Chevrolet Performance engineers knew this because they experimented with several of them during the development of the ZZ632 crate engine and other projects over the years. Some were better than others in their evaluations, but more than airflow capacity they were looking for a dual-range solution in the ZZ632 that would enable the sort of high-rpm horsepower that big-volume heads offered, but also with low-speed capability that would make the engine suitable for regular street driving.

“We looked at many aftermarket options but came back to the Chevrolet design that was known to work but never got a chance to really prove itself,” Alin Dragoiu, Chevrolet’s design release engineer for the engine, says. “We challenged ourselves with the ZZ632 to deliver at least 1,000 hp on pump gas and this head design would help us achieve that. It was the perfect base to build on.”

So, the engineering team pulled Sperry briefly out of retirement and enlisted his assistance in optimizing the design for the new, 632-cube crate engine (the original Pro Stock engine was limited to 500 ci). Chevrolet rewarded Sperry’s consultancy by naming the heads for him: RS-X.

They’re unquestionably the heart of the ZZ632 but delivering the air to them falls on an equally capable induction system featuring an all-new, high-rise single-plane intake manifold and the biggest EFI throttle body Wilson Manifolds had to offer.

When it comes to the spark part of the equation, there’s a crank-trigger ignition system that, along with LS/LT-style individual coils, enables the sort of timing control that allows this 12.0:1-compression big-block to make its 1,004 horses on 93-octane pump gas.

“We couldn’t get away with such high compression without these features,” Dragoiu says. “They enable the balance we’re able to strike between low-speed streetability and the high-rpm performance of a racing engine.”

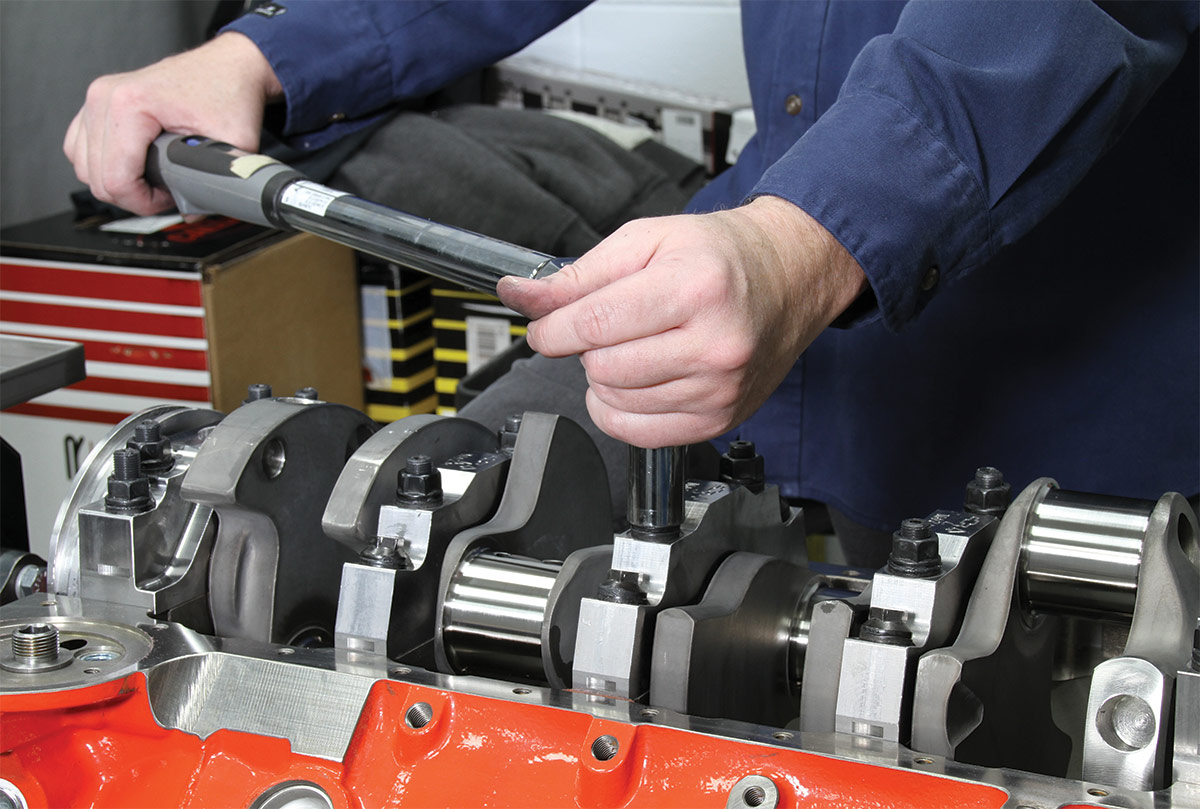

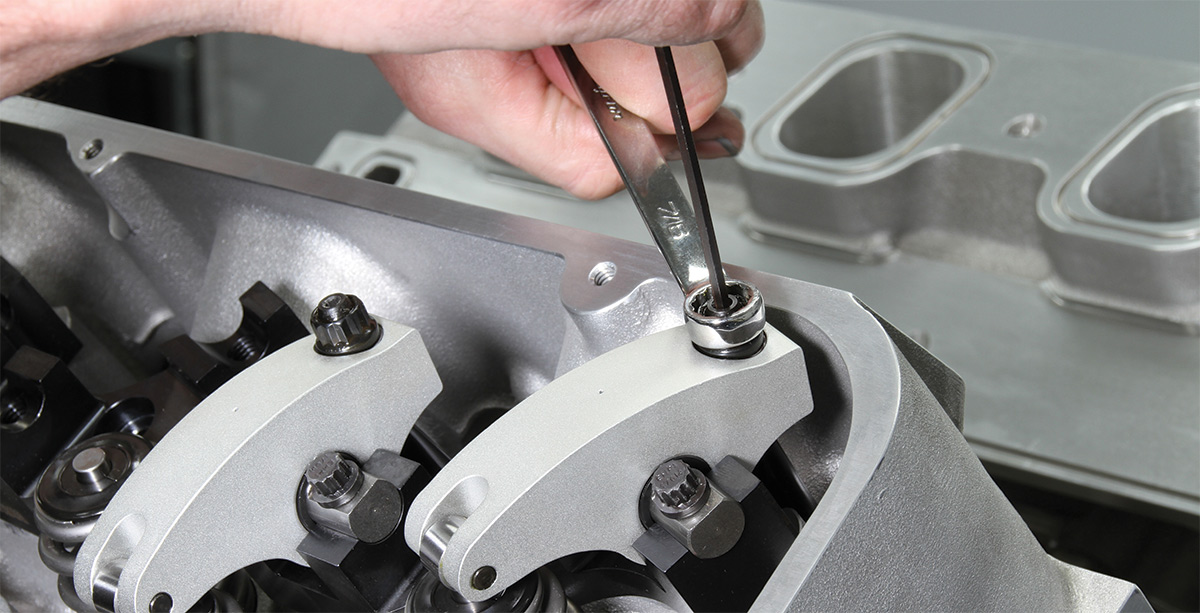

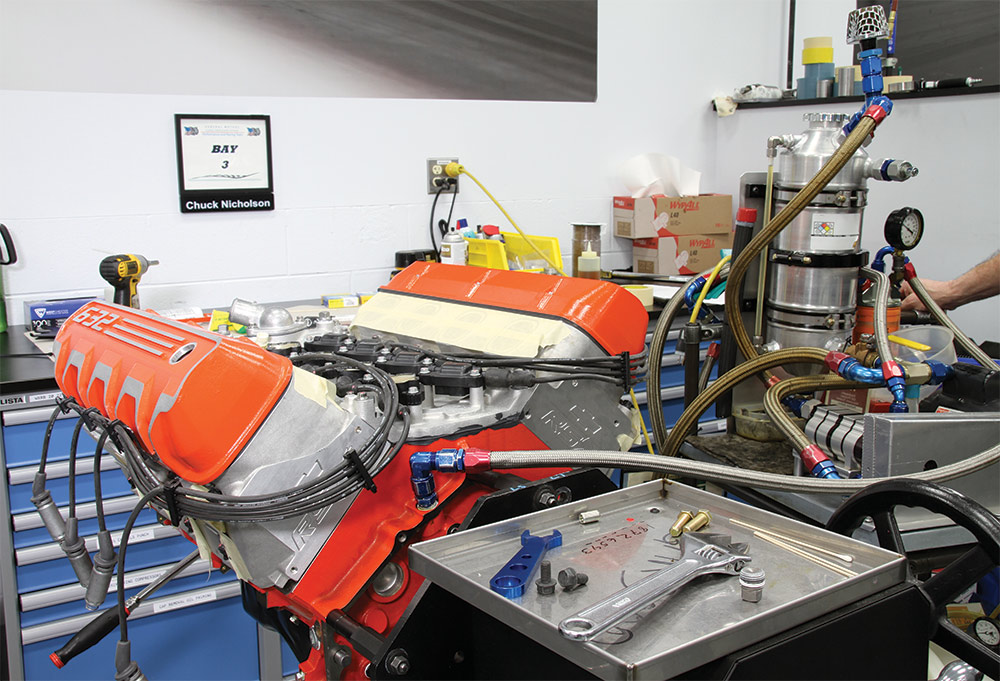

In fact, as we mentioned in the first installment, Chevrolet treats the ZZ632’s assembly very much like a racing engine. It is built by the same technicians as other racing engines, such as the COPO program, the Corvette Racing program, and more, with hand assembly from start to finish by a single builder—a process that doesn’t happen with other production-based crate engines.

“This is a very unique crate engine for Chevrolet Performance, with performance capability unlike anything else in the portfolio,” Dragoiu says. “So, we take extra care to ensure every last detail on the assembly.”

The ZZ632 blends the big-block’s incomparable and time-honored displacement advantages with contemporary technologies to take crate-engine performance to a new threshold.

Follow the photos as we wrap up the assembly with heads that have finally gotten their due, after more than 30 years.