Wiring Upgrade

Old-School Build, Part 2

Wiring Upgrade

Old-School Build, Part 2

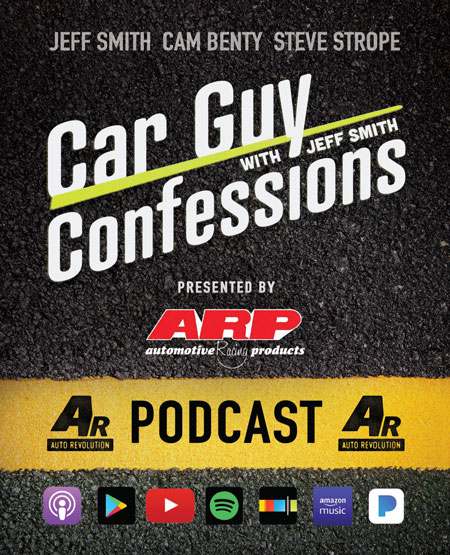

TOC

TOC

Photography by Wes Allison

Wes Allison, Tommy Lee Byrd, Ron Ceridono, Grant Cox, Dominic Damato, Tavis Highlander, Jeff Huneycutt, Barry Kluczyk, Scotty Lachenauer, Jason Lubken, Steve Magnante, Ryan Manson, Jason Matthew, Josh Mishler, Evan Perkins, Richard Prince, Todd Ryden, Jason Scudellari, Jeff Smith, Tim Sutton, and Chuck Vranas – Writers and Photographers

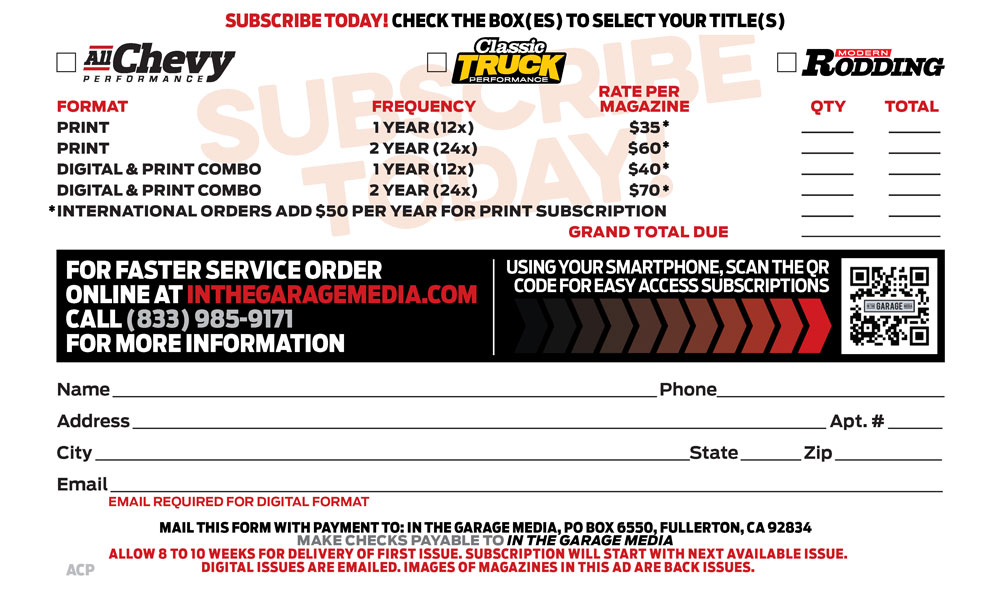

AllChevyPerformance.com

ClassicTruckPerformance.com

ModernRodding.com

InTheGarageMedia.com

subscriptions@inthegaragemedia.com

Mark Dewey National Sales Manager

Patrick Walsh Sales Representative

Travis Weeks Sales Representative

ads@inthegaragemedia.com

inthegaragemedia.com “Online Store”

info@inthegaragemedia.com

Copyright (c) 2022 IN THE GARAGE MEDIA.

PRINTED IN U.S.A.

FIRING UP

FIRING UP

BY NICK LICATA

BY NICK LICATA

pparently, that reoccurring subject of electric-powered muscle cars is a hot topic these days. Case in point was at the 2021 SEMA Show in Las Vegas, a certain high-profile yellow ’57 Chevy showed up with an electric motor underhood. Needless to say, that didn’t go over very well with the majority of muscle car enthusiasts who have been following that magazine project car for decades, as they voiced their displeasure rather loudly on social media. Many of the comments were brutally honest and even more were just plain brutal. Most were upset to see an iconic muscle car known for having robust power surprisingly morph into a spokesmodel for EV power—and not much at that.

For those who have been playing with cars and reading automotive magazines for years might remember the early to mid ’70s when the sky fell on everything muscle car related due to the gas crunch of the era, which sent fuel prices to the moon. So, how did the magazines respond? By doing articles on how to get more horsepower from your ’70s-era Vega or Pinto. Suddenly there was a plethora of information on how to get more horsepower out of your four-banger, including head-porting and just about every bolt-on you could imagine.

Most readers just glazed over those articles and did what any red-blooded hot rodder would do: Move forward with V-8 swapping their econobox. It didn’t really matter that the magazines continued to cover how to get more ponies from their half-sized engines, these guys were more interested in shoehorning bigger cubic inches where smaller cubic inches once resided.

Parts Bin

Parts Bin

For more information, contact Scotts Hotrods ‘N Customs by calling (856) 951-2081 or visit scottshotrods.com.

For more information, contact Wilwood Disc Brakes by calling (805) 388-1188 or visit wilwood.com.

For more information, contact Summit Racing by calling (800) 230-3030 or visit summitracing.com.

CHEVY CONCEPTS

CHEVY CONCEPTS

Text and Rendering by Tavis Highlander

Text and Rendering by Tavis Highlander

n 2003, Chris McClintock started this Nova project with the intention of using it as a rolling business card to promote his new upholstery shop Bux Customs. Like many projects, elements were finished as time was available and the car ended up at the 90 percent mark years later. With the upholstery business flourishing, the little Nova was sidelined, but its time has come for a thorough refresh.

A 6.0L backed by a T56 had been installed early on and remained while many other pieces were updated. A new Scott’s Hotrods frontend, Schott wheels, and Clayton pedals are some of the upgraded parts that are now being installed on the wagon. Some metal and mechanical work is being performed by Steel Town Garage in Birdsboro, Pennsylvania, for extra safety. Vaughn’s Restoration in Norristown, Pennsylvania, will handle the paint and body.

Which color combo should Chris go with? We’ve narrowed it down to three, and the toughest choice is now picking the final one!

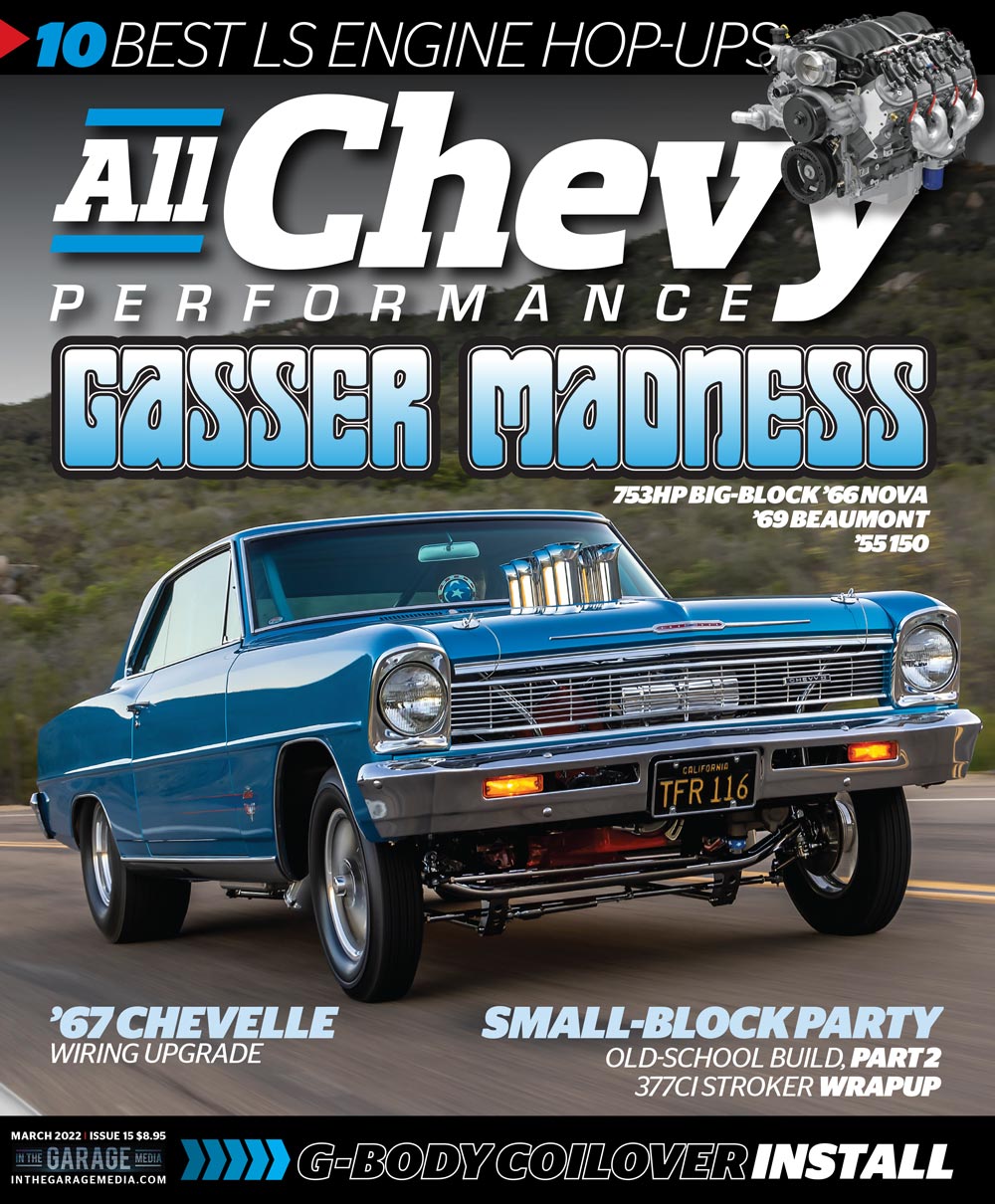

FEATURE

FEATUREhere seems to be a bit of a resurgence in what is commonly referred to as the “gasser style”—cars built with a straight-axle or dropped-axle frontend, aiming the nose sky high to replicate the look of the AF/X and Gasser drag racing class cars of the ’60s, and we absolutely dig it. The look is totally old school and cars built with this personality are rewarded with tons of attention wherever they are spotted.

Photography by Wes Allison

Photography by Wes Allison

TECH

TECH Photography by The Author

Photography by The Author

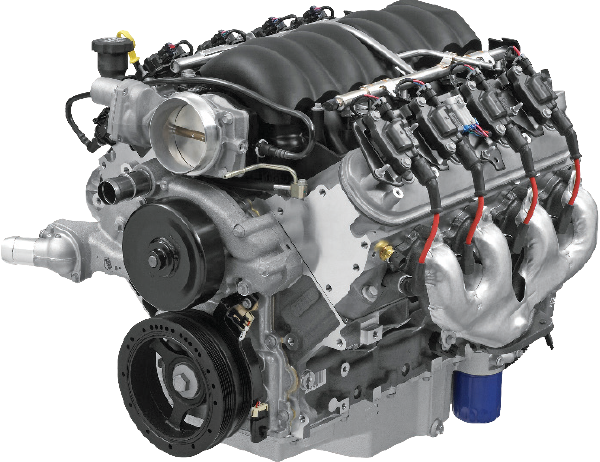

Smart Spending Strategies for Building Your Next LS Engine

Smart Spending Strategies for Building Your Next LS Engine Photography by The Author

Photography by The Author Smart Spending Strategies for Building Your Next LS Engine

Smart Spending Strategies for Building Your Next LS Enginefew years ago, a colleague of ours spent more than a few bucks to elevate the performance of his LS1-powered fourth-gen Camaro SS. It was a bolt-on extravaganza, with long-tube headers, a snazzy-looking intake manifold upgrade, and a larger throttle body, along with a cold-air intake and more. The engine looked great under the hood and sounded even better through the headers.

On the chassis dyno and with proper tuning, power to the tires definitely increased, but the gain wasn’t dramatic. Worse, the car’s crisp street performance was dulled like your mom’s old caravan down a cylinder or two. To put it nicely, it was a dog, particularly at low rpm, where what little torque the LS1 made down there all but evaporated.

It’s all because our buddy took the traditional bolt-on approach to building horsepower—the things we all grew up reading about when people were trying to coax an extra 25 hp out of a smog-laden two-barrel small-block. Opening up the restrictive intake and exhaust systems were the keys to make 275 hp back then, but it’s the total opposite with an LS engine.

FEATURE

FEATURE Photography by John Jackson

Photography by John Jackson

M’s first outing with the stylized and sporty F-body was just the beginning of what was to become arguably the most popular muscle car of all time: the ’69 Camaro. Not to take away from the ’67 though, which has a strong following of windwing fanatics who praise this incarnation of the first-gen Camaro. There’s no doubt GM came out swinging into the ponycar wars, as it was an absolute hit with young drivers of the late ’60s. The marketing worked and the car worked even better. In no way could the designers of this car imagine it would remain so popular well over 50 years later, but here we are.

Jim Vogel had always had a hankerin’ for a first-gen Camaro, but never pulled the trigger. That was until he spotted a promising ’67 at a used car dealership in Detroit. The body style was the main attraction but at some point he wanted a vintage car with all the modern accoutrement to make it run and handle like a late-model hot rod similar to his ’15 ZL1 Camaro.

Jim finally pulled the trigger on the Camaro and drove it for a while until the newness wore off, which happened rather quickly. It didn’t handle well, stop well, and its ability to accelerate left him kinda flat, too. But he wasn’t totally caught off guard as he had low expectations for the vintage ride’s performance, or lack of it. Knowing full well at some point the car would go through a complete resto, it wasn’t long before he wheeled it from his home about 7 miles down the road to Automotion Design and Fabrication in Obetz, Ohio, for a body-off restoration and a Pro Touring treatment. He needed his new pride and joy to become the car he’d always wanted.

TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

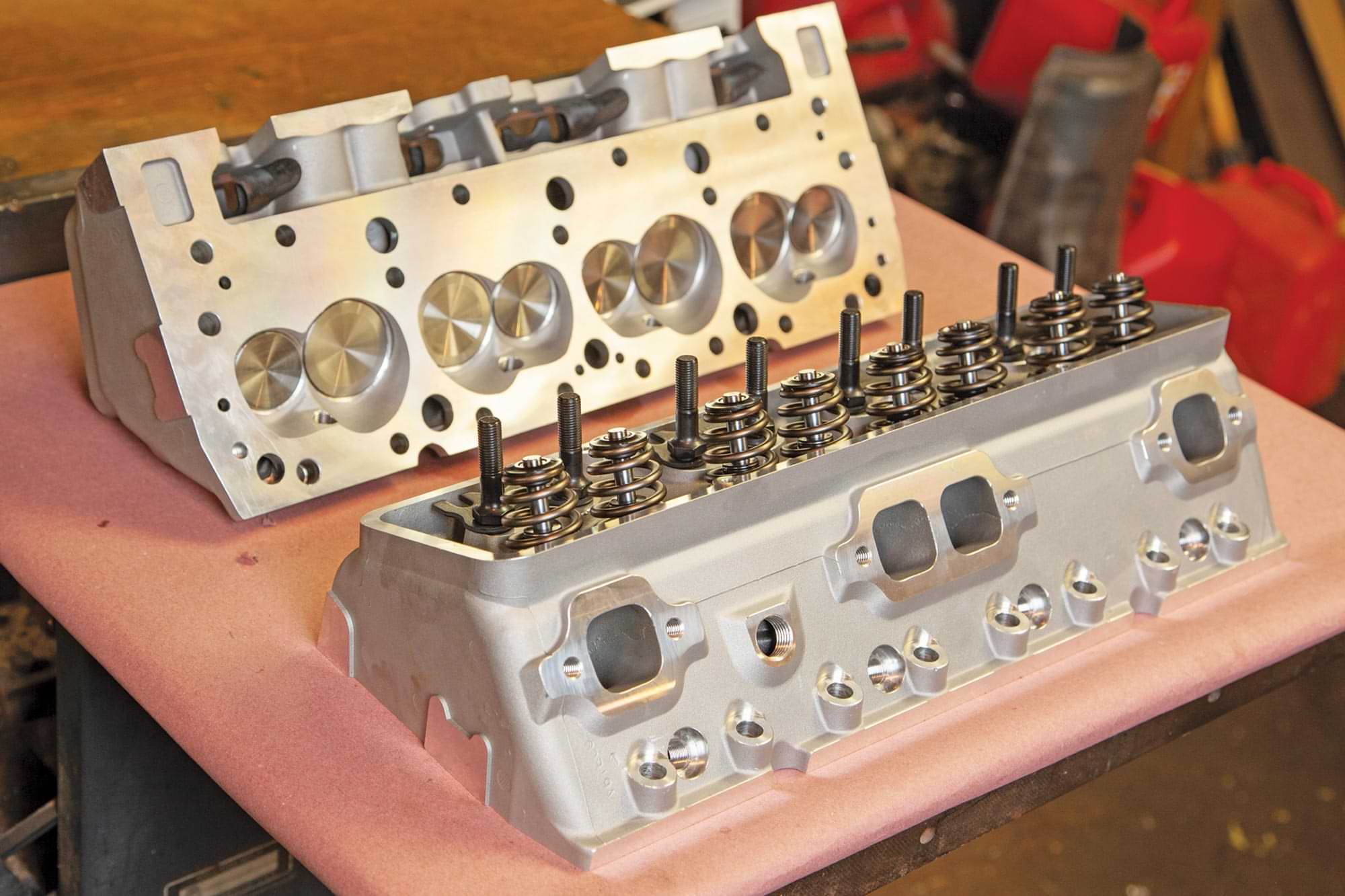

Photography by The Authorf you have been following along, in last month’s issue we gave you the rundown on how we assembled the bottom end in our little homebuilt small-block Chevy. Now comes the fun part—heads, valvetrain, and the finishing touches. Working with a basically stock rotating assembly, it’s still very feasible to squeeze out some extra power. The next big priority was bolting on a great set of heads. It’s a practice hot rodders have played with for over a century, and the concept is simple: higher compression plus better airflow equal more power. But we also wanted to be careful not to sacrifice reliability and driveability.

The horsepower per dollar scale is always tough when you’re on a budget. You want that best-bang-for-your-buck type of thing. Reliability and longevity are worth something, too. I was looking for the best of both worlds when it came to the engine—that perfect mix of driveability but with an old-school muscle vibe.

When you dive into it, it’s not hard to find a great set aftermarket heads, or even factory options when budget is a high priority. A set of iron Vortecs (L31 ’96-00 truck and SUV) could work for some applications, but with higher-lift cams they require additional machine work at additional expense. After some cost analysis and shopping around, I looked to Speedway Motors for help.

FEATURE

FEATURE Photography by The Author

Photography by The Author

rag racing has changed a lot since the gasser wars of the ’60s. The basic principles are still the same, but the manner in which they’re accomplished is wildly different. This is the case at the majority of dragstrips across the country, where modern marvels impress the masses with seemingly effortless quarter-mile passes.

Meanwhile, Terry Housley, a 45-year drag racing veteran from Lenoir City, Tennessee, took a few steps back from the modern approach of drag racing, having spent a couple decades behind the wheel of various drag cars. Terry strapped himself into a car that requires max effort and commands the attention of everyone in the stands when he pulls to the line. This ’55 Chevrolet is purpose-built to replicate a car that would’ve competed in NHRA’s Gas Coupe and Sedan class during the mid-to-late ’60s. Terry and his son, Blake, built this car to compete in the Southeast Gassers Association, which is a group of dedicated racers who believe in paying tribute to the pioneers of the sport.

TECH

TECHTested, Tuned & Torque for Days

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authoruilding an engine from scratch isn’t a relatively difficult thing to do so long as one is fastidious and pays attention to all the details. It’s also very rewarding (albeit stressful) when that handbuilt engine is fired for the first time and put through its paces on the engine dyno. There’s a bit of a pucker factor to be sure, but the satisfaction of a job well done is much more gratifying than dropping that credit card on a crate engine. Building an engine from the ground up also gives one a better idea of what’s going on inside the engine, making diagnosis and repair easier. And for some of us, just getting our hands dirty and spending the time in the shop building something is better therapy than any fancy spa can provide!

We wrapped up the build side of the engine in our previous story, but that doesn’t mean that things were complete. As it were, we still had to add the induction and ignition components before our date with the guys at Westech Performance Group in Mira Loma, California, arrived. Which brings us to the importance of utilizing an engine dyno when building custom engines. Installing an engine in a vehicle and getting things in running order is no small feat. There are a myriad of electrical and plumbing connections that need to be made, fluids added, exhaust built and installed, torque converters, bellhousings, and so on. Going through all that work just to find something in need of repair that requires the removal of that new engine can be frustrating, to say the least. But by running the engine beforehand on an engine dyno, any little finicky issue can be addressed beforehand and in a situation that makes doing so much easier. It also presents a convenient environment for initial break-in, saving your neighbor’s nerves to be tested another day.

FEATURE

FEATURE

Photography BY The Author

Photography BY The Authorh Canada! How we love your majestic mountains, ice-cold brewskis, and gooey maple syrup. Your polite citizens make us feel right at home when we cross the border, and the country’s spotless cities and raucous hockey arenas make us want to go through customs time and time again.

Though Canada is clearly a worldwide leader in many of the things stated above, we can still find most of them (to some extent) right here in the good ol’ USA.

However, there are a few things that rarely cross the Canadian border into the lower 48. And I’m not talkin’ Wayne Gretsky or even Tim Hortons badass cup o’ joe. I’m speaking automobiles—the special models built by GM Canada back in the heyday of muscle rides—the sporty Acadian, and the car at the top of the muscle car food chain, the A-body–based Beaumont.

Albert Galdi of Somerset, New Jersey, is a muscle car aficionado and GM addict who just can’t get enough of the company’s A-body platform. Over the years, he’s tended to quite a few top-notch restorations on models from the ’60s and ’70s and has wrenched these rides into award-winning examples.

TECH

TECH BY Jesse Kiser

BY Jesse Kiser  Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorince its completion, our ’82 Malibu Wagon hasn’t experienced a significant breakdown … yet. A fun, reliable street cruiser, it wasn’t until our first autocross at UMI Motorsports Park that we discovered its performance shortcomings. We spun out in clouds of smoke, murdered some cones, and went home with a lackluster finish. The combination of the wagon’s parts—750-rwhp LS1, built 4L80E, Strange Engineering 9-inch, and UMI Stage 3.5 tubular suspension—is unrealized. Our wagon has untapped potential. Luckily, that’s what an East Coast winter is for: more projects.

The wagon is a family hauler, burnout monster, and great street car, but we want to turn up the heat: A T56 six-speed manual swap so we’re always in the right gear, a Holley Terminator X for better tuning, and Aldan coilovers for better road response and adjustability. We’re starting with possibly the easiest of them all: coilovers, so we installed Aldan American coilovers on our Chevy G-body.

FEATURE

FEATURE

Photography BY Jason Matthew

Photography BY Jason Matthewtarting a vintage muscle car build from the ground up is a tall order—doing it for a second time is a next-level time suck that no one cares to deal with, but Lou Baltrusaitis did just that. With his ’69 Camaro ready to hit the body shop for final sanding and paint, Hurricane Sandy hit Lou’s place and filled the car with water. “Sadly, we had to take the car apart and completely redo it,” Lou states. “There was water throughout the whole house and unfortunately the car got it, too.”

TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

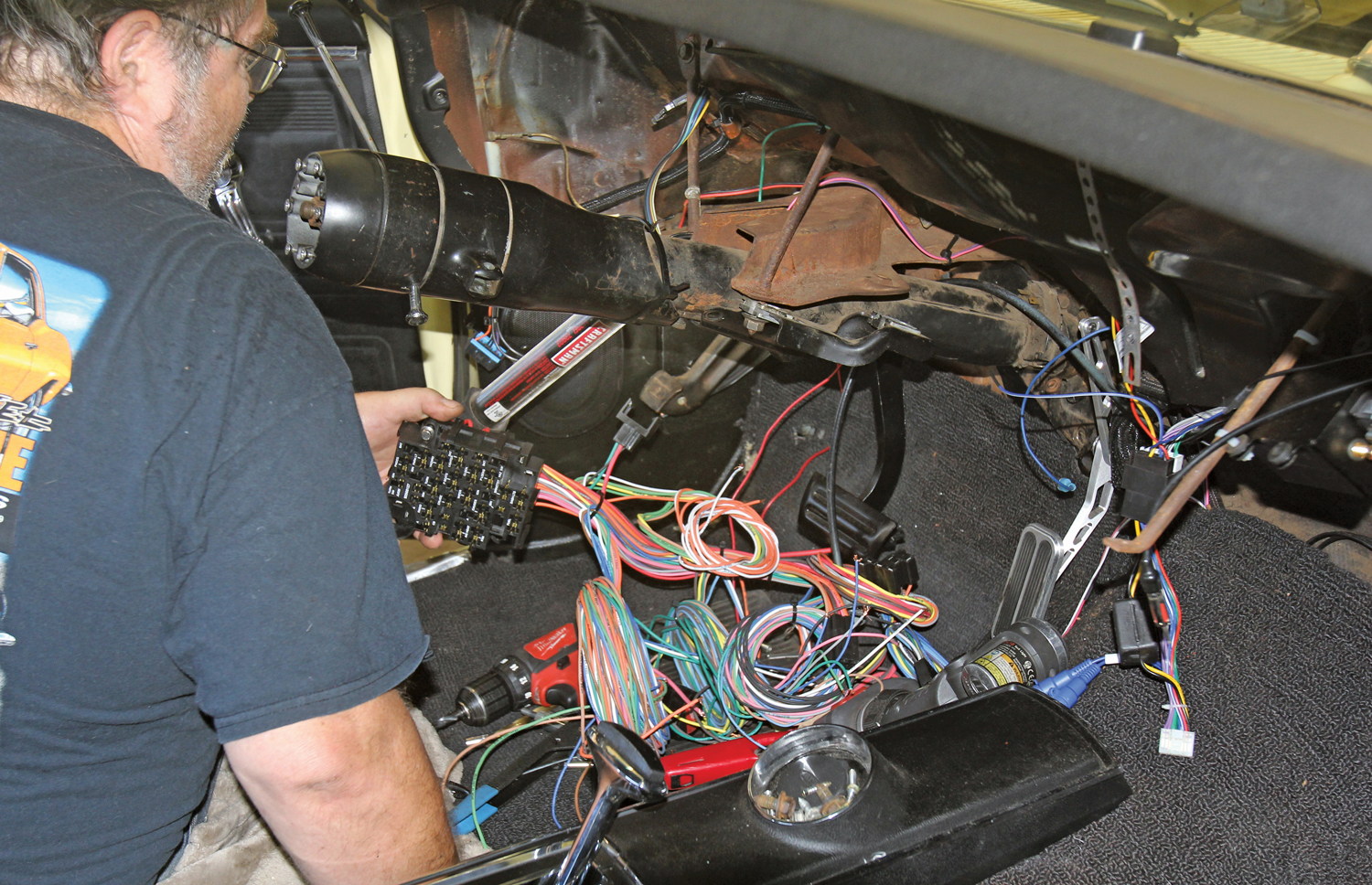

Photography by The Authort’s an unavoidable fact of life. The object of our ’60s and ’70s Bowtie muscle car affections are well past long in the tooth. They are well past silver anniversaries and are sneaking up on 60 years of extended service. Time tends to take its toll on items that we often take for granted—like the electrical system.

Another fact of muscle car life is that electrical systems also suffer some of the greatest abuses. Electrical hacks, botched wiring attempts, cheesy add-on mistreatment, and a host of other sticky black electrical tape exploitation over decades of modifications have left these machines often in need of attention.

Advertiser

- Aces Fuel Injection87

- Aldan American79

- American Autowire57

- Art Morrison Enterprises27

- Auto Metal Direct7

- Auto Revolution Online85

- Automotive Racing Products23

- Borgeson Universal Co.55

- Bowler Performance Transmissions85

- Classic Instruments13

- Classic Industries37

- Classic Performance Products4-5, 83, 92

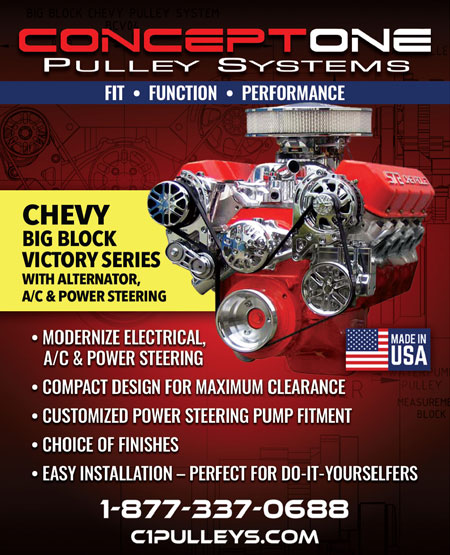

- Concept One Pulley Systems85

- Custom Autosound67

- Dakota Digital91

- Danchuk USA11

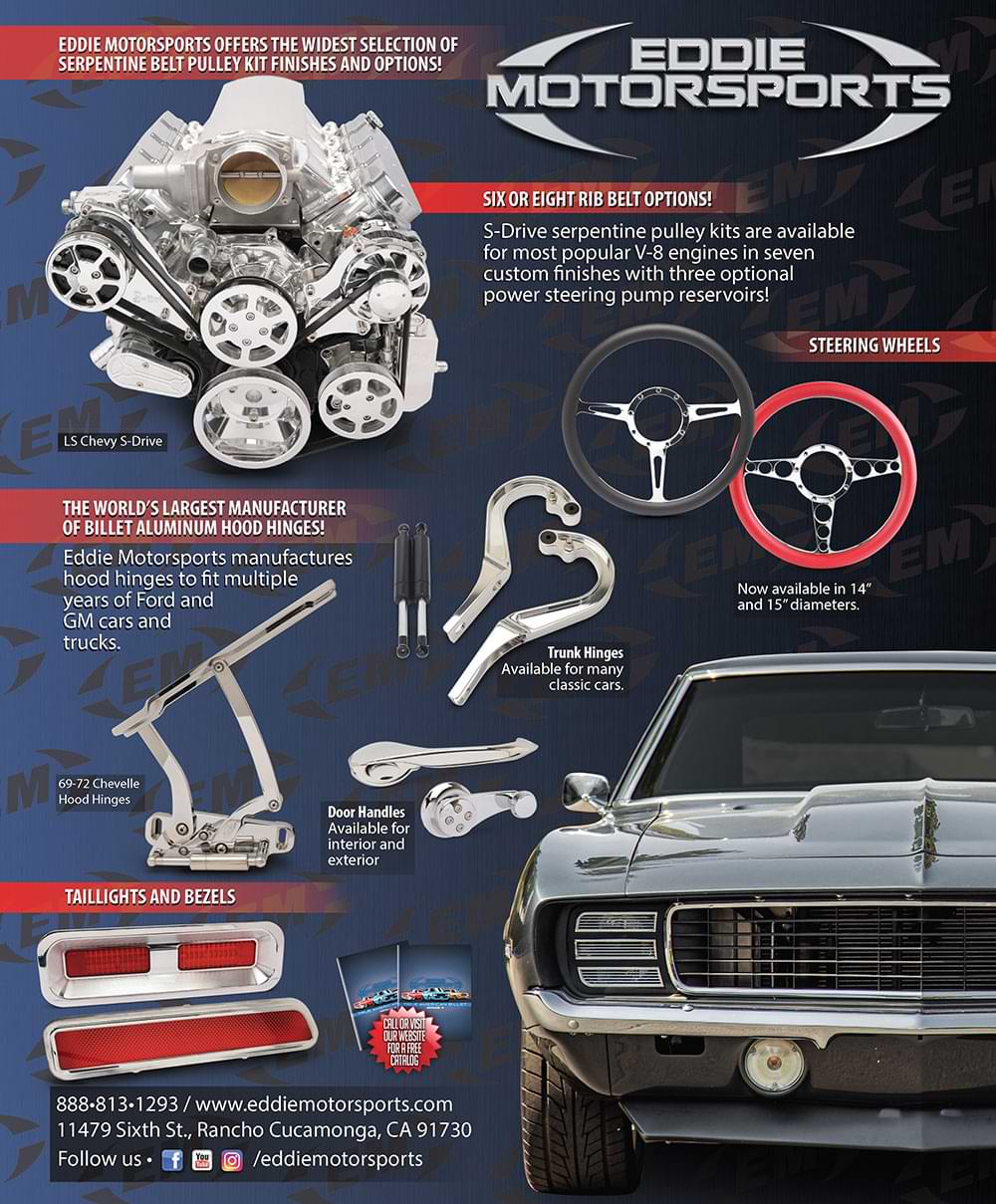

- Eddie Motorsports51

- FiTech EFI45

- Flaming River Industries41

- Granatelli Motor Sports71

- Heidts Suspension Systems65

- Holley12

- HushMat87

- John’s Industries85

- Lokar2

- National Street Rod Association59

- New Port Engineering83

- Original Parts Group29

- PerTronix9

- Powermaster Performance73

- Scott’s Hotrods ’N Customs73

- Speedway Motors35

- Strange Engineering67

- Summit Racing Equipment21

- Thermo-Tec Automotive83

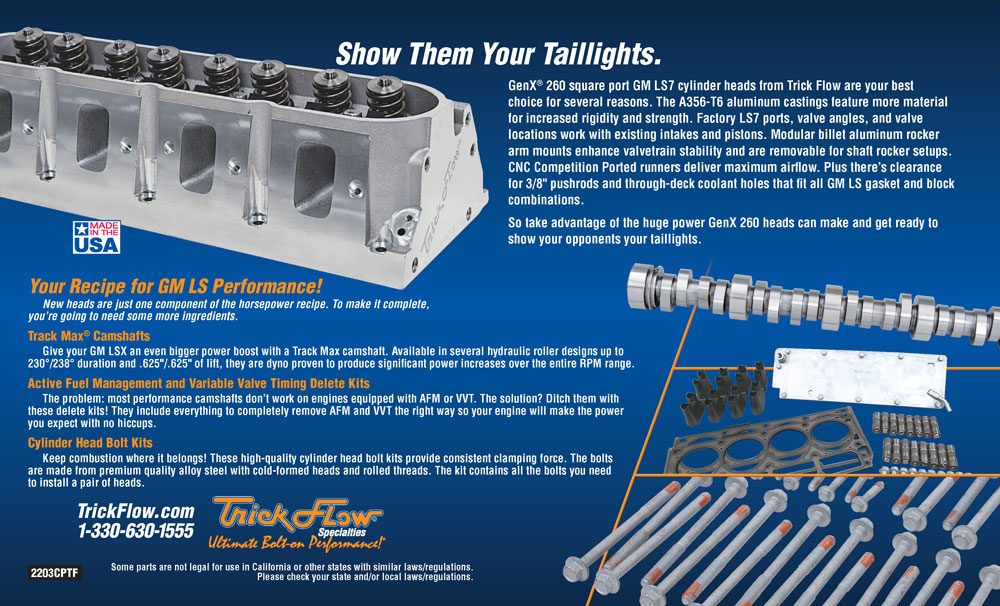

- Trick Flow Specialties65

- Tuff Stuff Performance Accessories71

- Vintage Air6

- Wilwood Engineering43

- Year One83

Bowtie Boneyard

Bowtie Boneyard

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorhe year 1929 was a big one for Chevrolet. That’s when the 194ci overhead valve (OHV) six-cylinder engine arrived as standard equipment in all Chevrolet passenger cars. This new six was just about as big a piece of news for Chevrolet–and its customers—as the small-block V-8 of 1955. Chevrolet marketed the new engine as “a Six at the price of a Four,” instantly rendering Ford’s existing flathead four obsolete. Better still, even though the 194-cube Chevy OHV six was 6 ci smaller than Ford’s 200-cube four-banger, it was 6hp stronger (46 hp versus Ford’s 40 hp).

Oddly, Chevrolet didn’t assign a spiffy, whizbang marketing name to the 194 six until 1934 when a revised cylinder head with canted exhaust valves and modified burn characteristics earned it the official title: Blue Flame Six. But among the general public, the rather generic-looking pan head fasteners securing the camshaft cover plate to the side of the engine block earned the title “Stovebolt Six.” These “Stovebolt Sixes” became so prevalent in the following decades that Chevrolets became known generically as “Stovebolts” among those of us with greasy fingernails, a term used well into the ’70s.