TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author

Photography by The Authorhen it comes to big-blocks, sightings of Chevrolet’s W-series engines are getting more and more rare out in the wild. But historically, they are incredibly important.

The W-series marked the first big-block offering for Chevrolet, which needed more power and torque for the increasingly heavy cars and trucks it was producing. The 348ci version came first and started showing up in 1958.

But that was the 348. Nobody sings great songs about the 348. The engine that everyone cares about when you’re talking about W-series engines is the famous 409. You know, the one that the Beach Boys sang about in the song … uh … “409.”

Yeah, it’s catchy, but it ain’t deep.

Anyhow, the 409 was the real performer. Although it didn’t have a long production life—appearing in ’61-64 model years—the 409 was one of the first American-made engines to break the 1 horsepower per cubic inch barrier when it was rated at 409 hp and 420 lb-ft of torque in 1962 thanks to dual Carter four-barrel carbs.

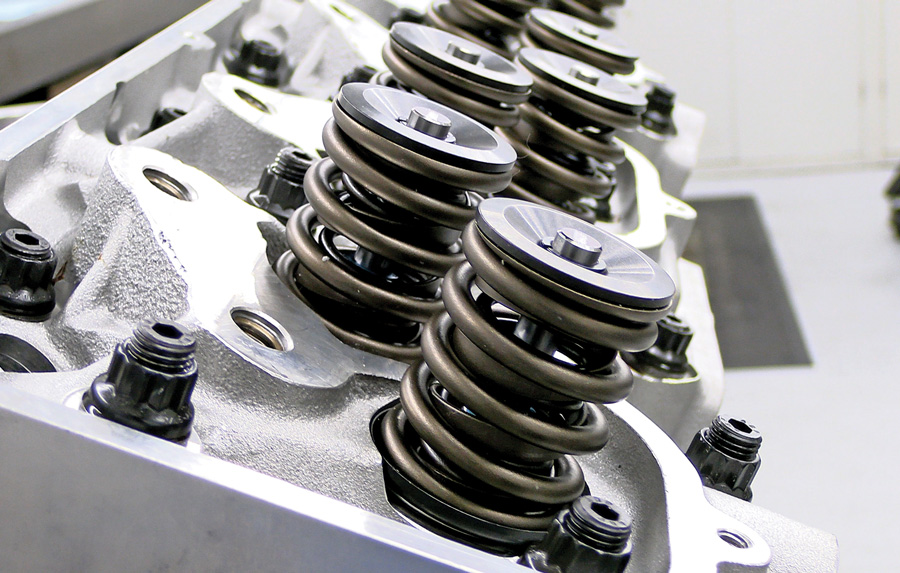

By 1963 that number improved to 425 and 425 with a solid flat tappet valvetrain. And that’s not even counting the infamous Z11 variant that was punched out to 427 ci with 14:1 compression and was rumored to produce nearly 500 hp. Of course that was simply a homologated drag race engine and only a tad more than 50 were ever sold to the public.

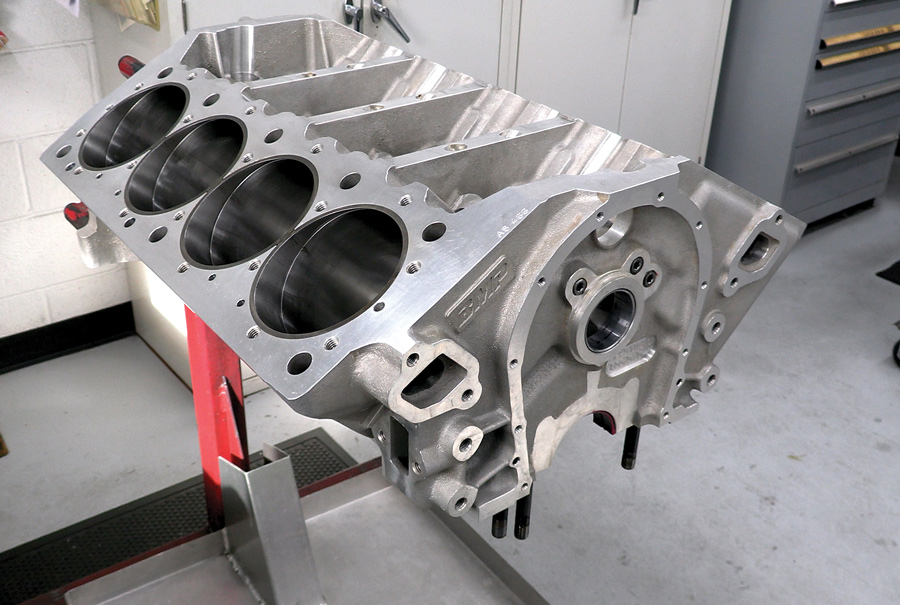

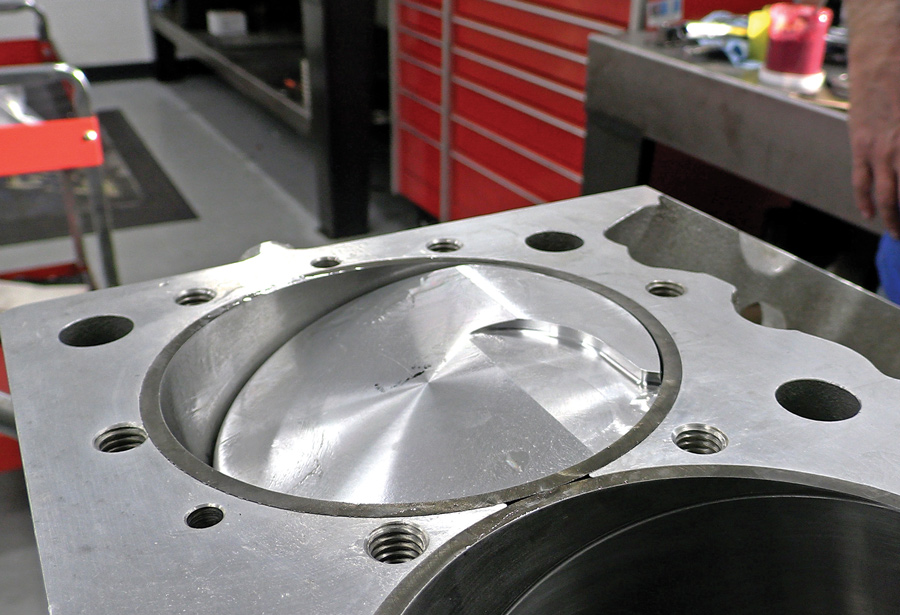

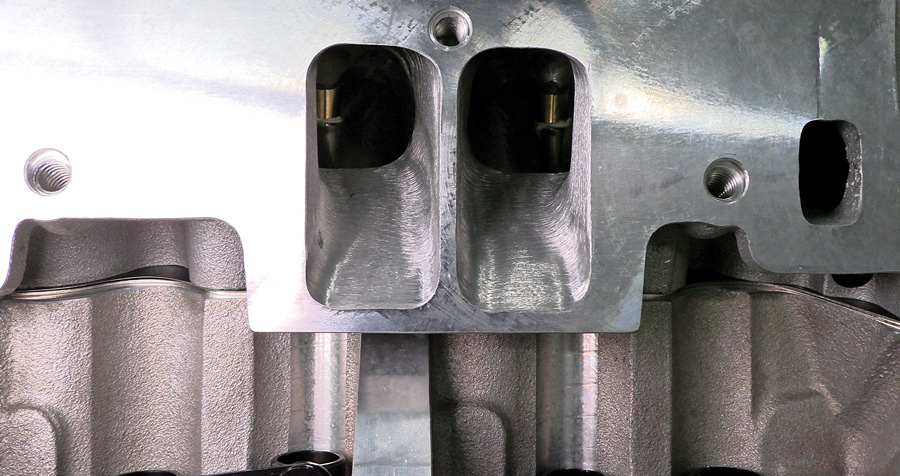

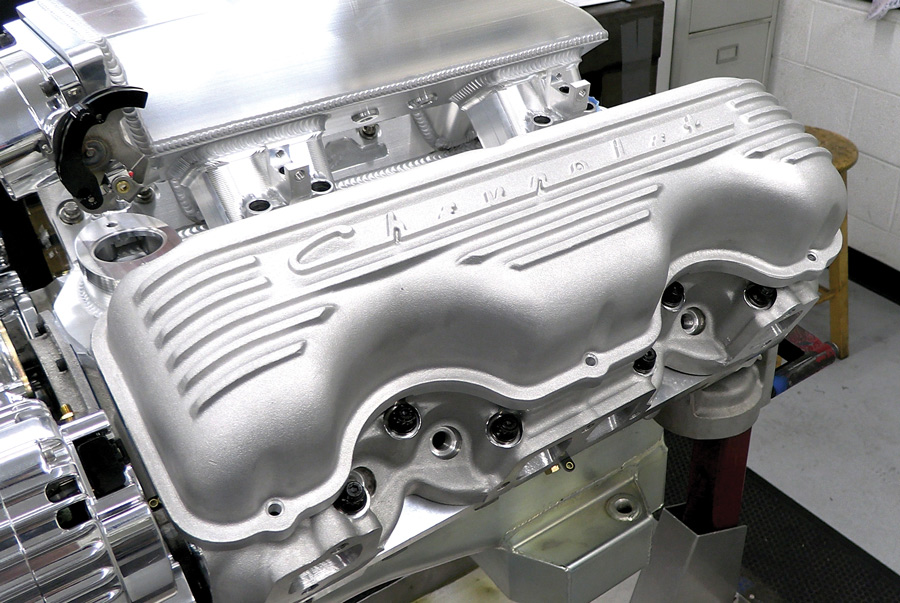

The 409 and 348 are quirky engines because the combustion chamber isn’t in the cylinder head but is in the block. The deck of the block is 74 degrees to the centerline of the crankshaft where almost all other engines are 90 degrees. That creates a wedge-shaped void between the top of the piston and the deck of the cylinder head for a combustion chamber.

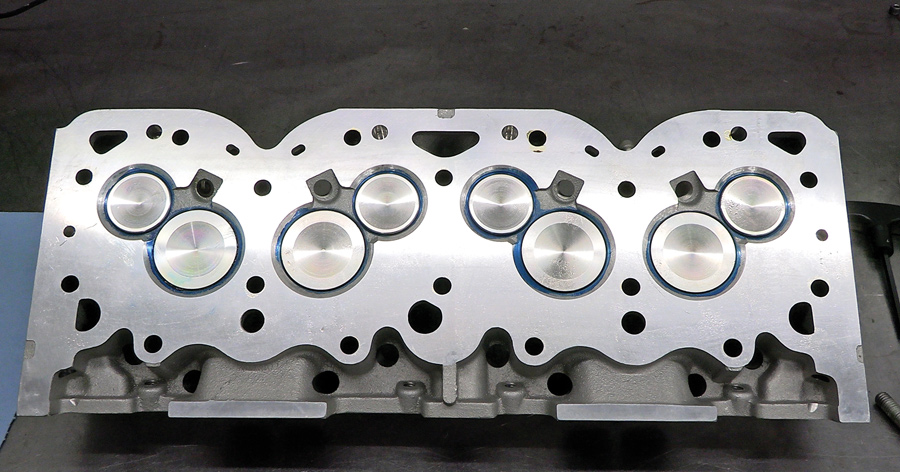

Chevrolet’s engineers apparently knew early on that they were at a disadvantage against the Mopar Hemi and Ford’s big FEs, and the Mark IV big-block first appeared on ’65 model year vehicles. The Mark IV big-blocks kept the 409’s 4.84-inch bore spacing but otherwise it went with a more conventional 90-degree deck and combustion chambers in the cylinder heads.

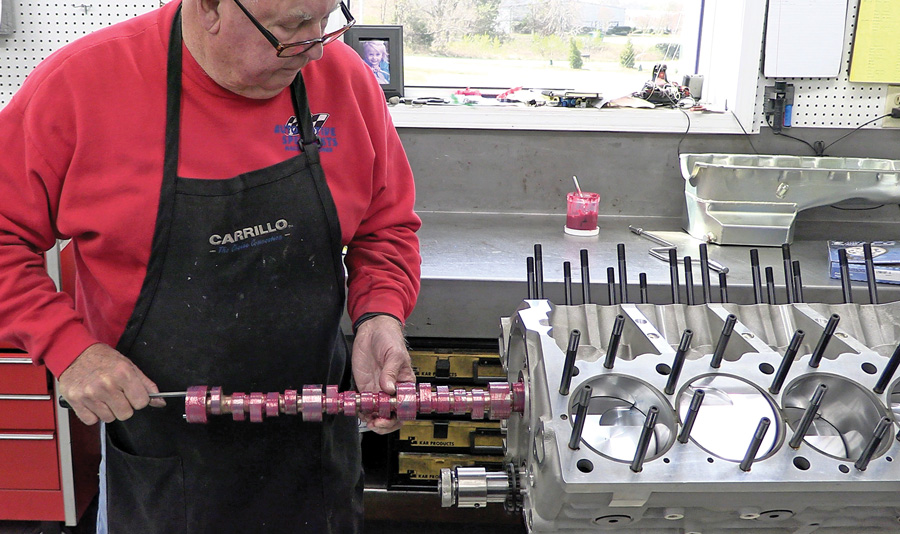

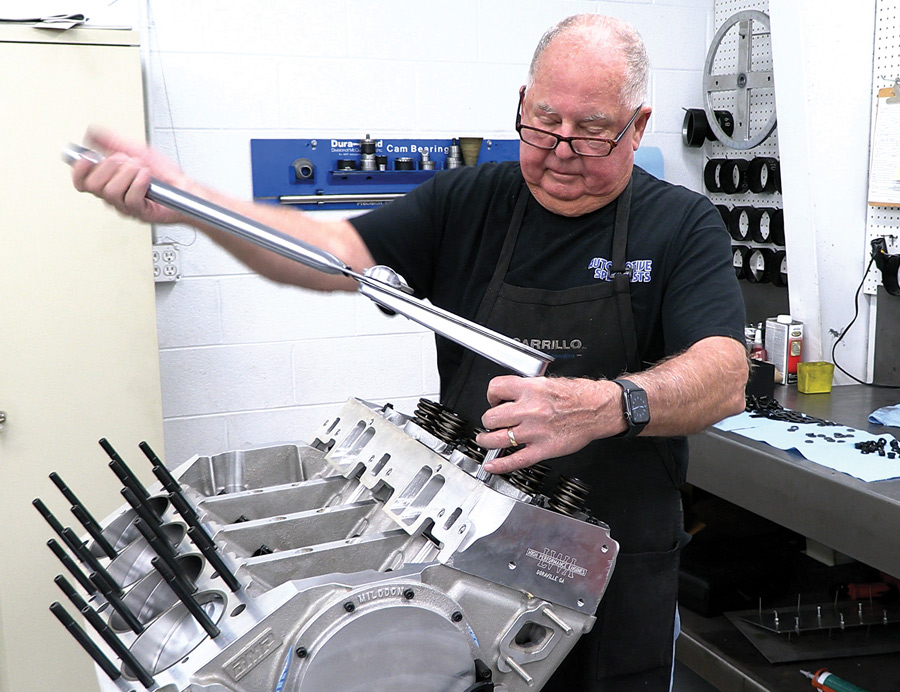

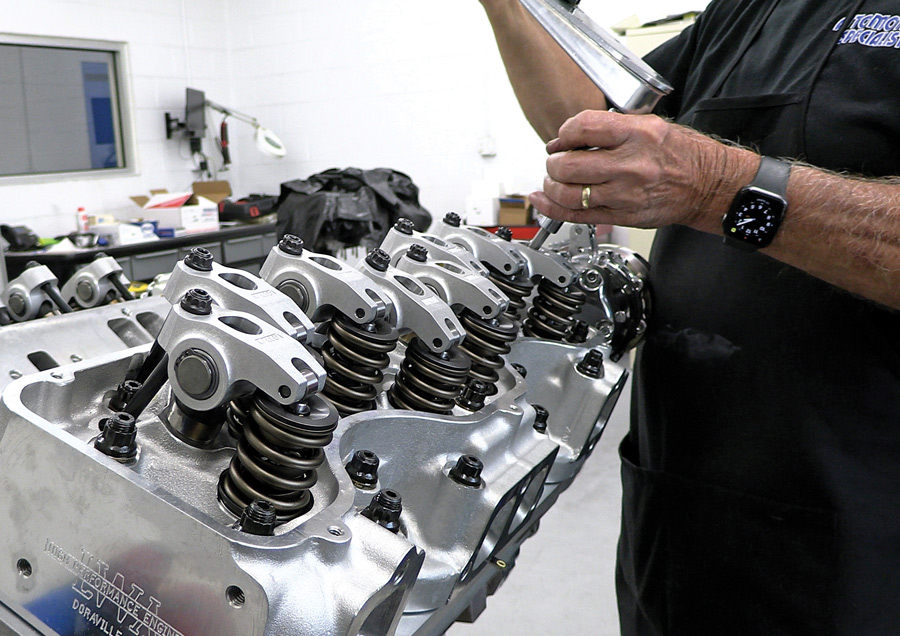

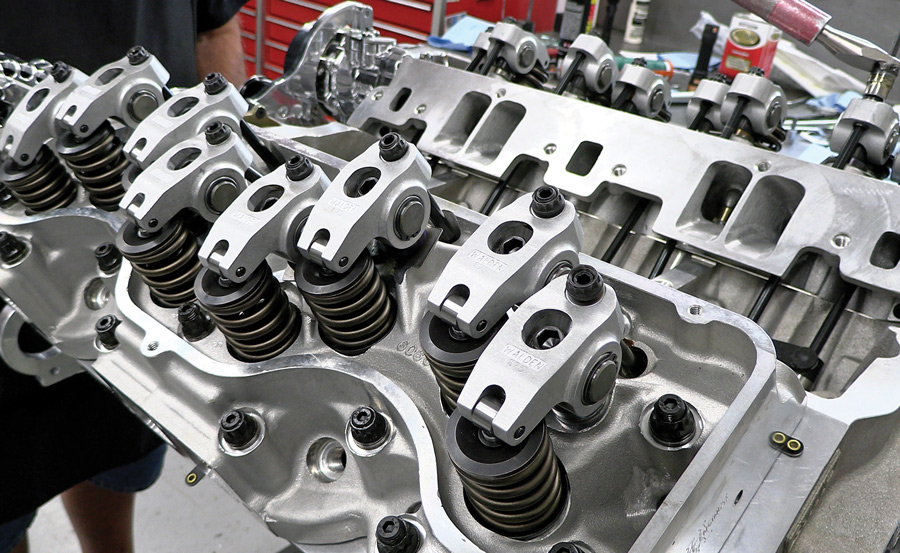

These days the aftermarket still offers a ton of support for both the first-generation small-block and the Mark IV big-block. But support for the W-series 409 is a lot more sparse. That was the challenge engine builder Keith Dorton, owner of Automotive Specialists, faced when a customer wanted a modernized 409 for his ’63 Impala restomod build.

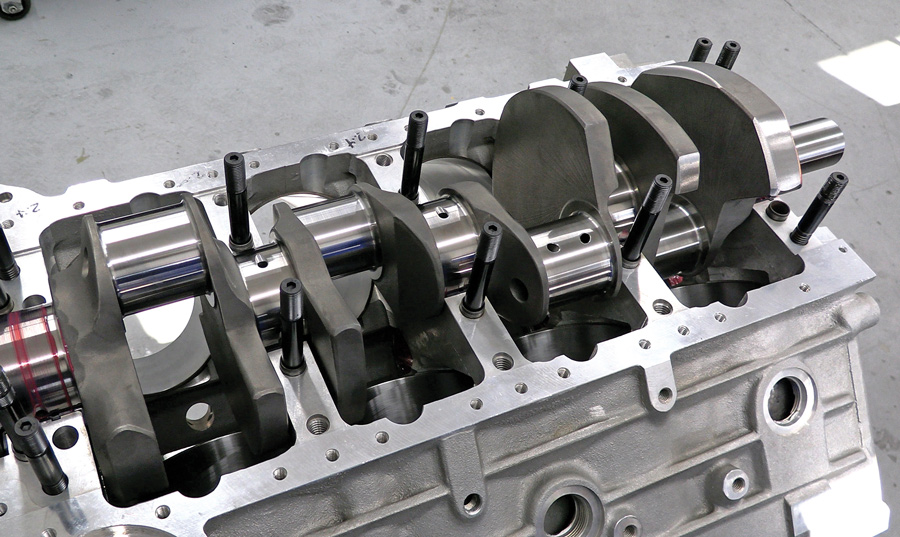

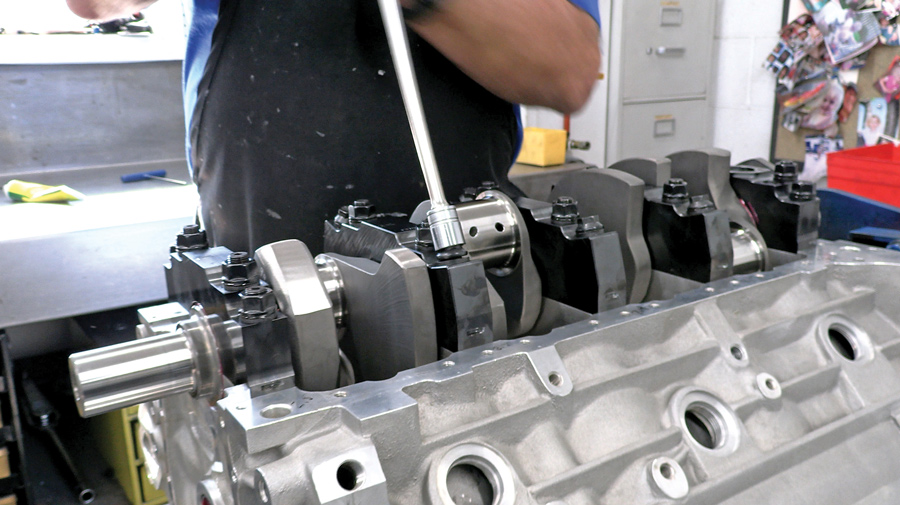

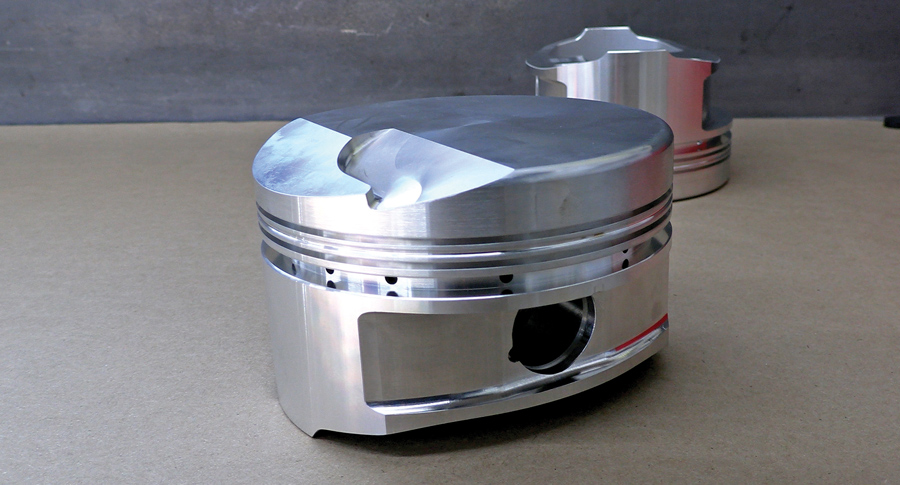

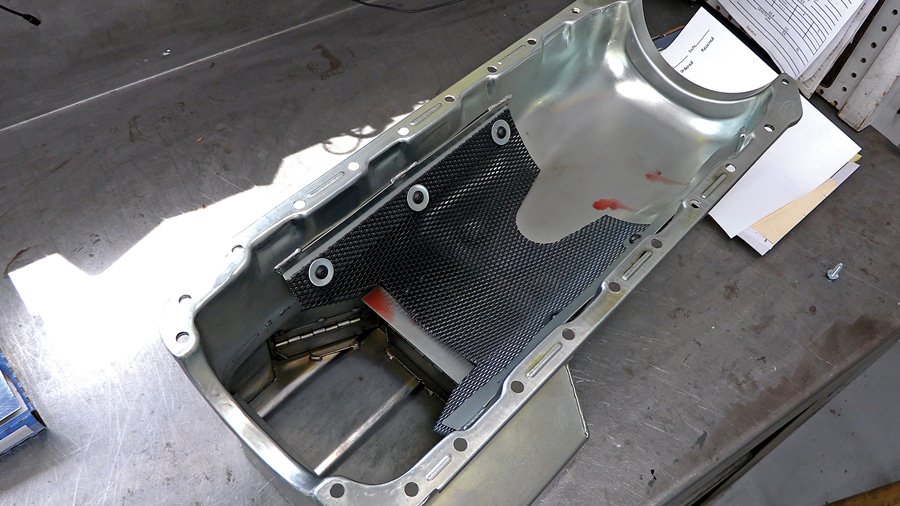

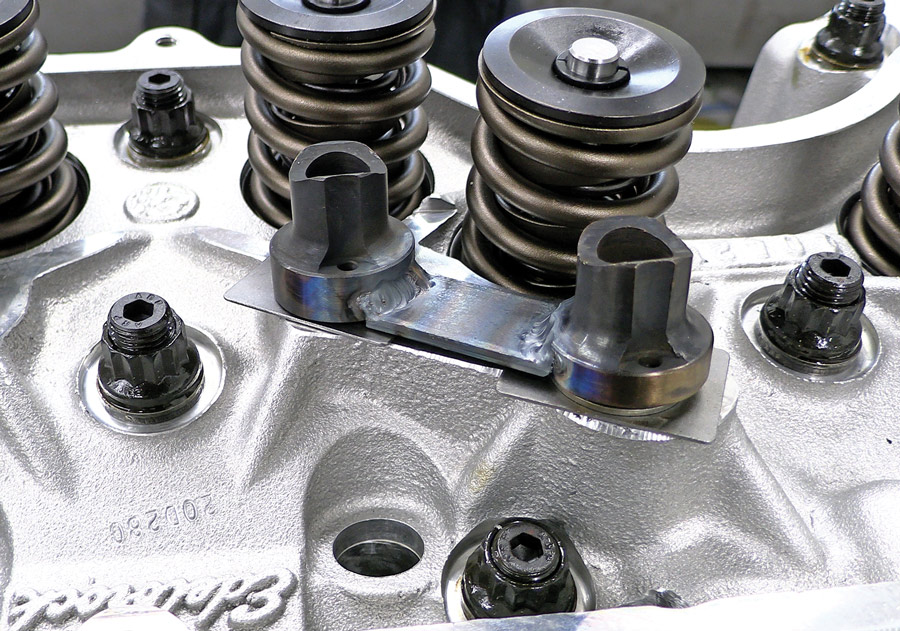

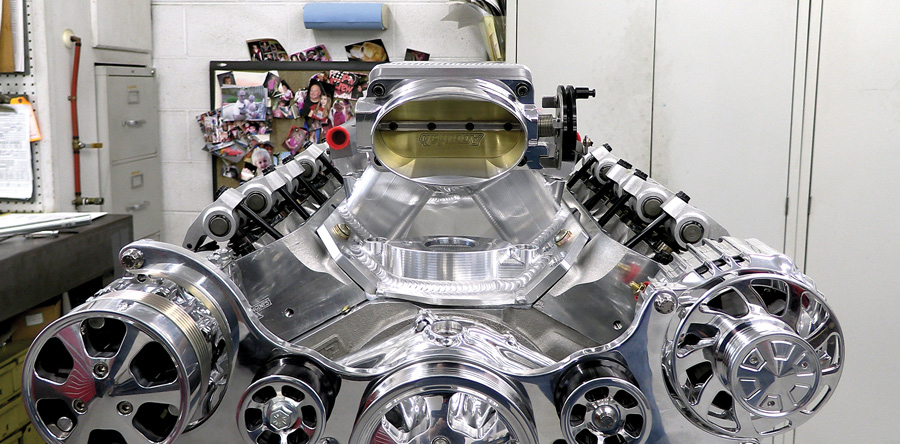

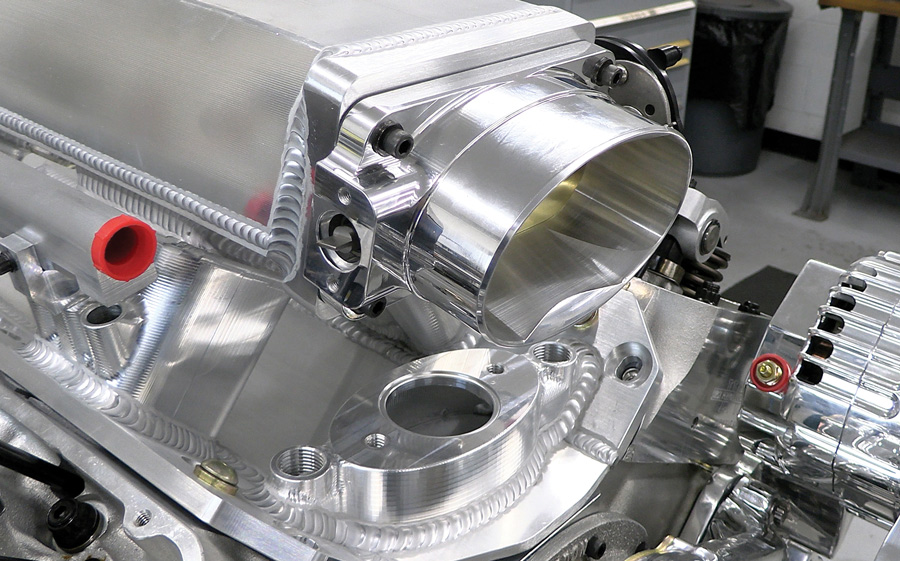

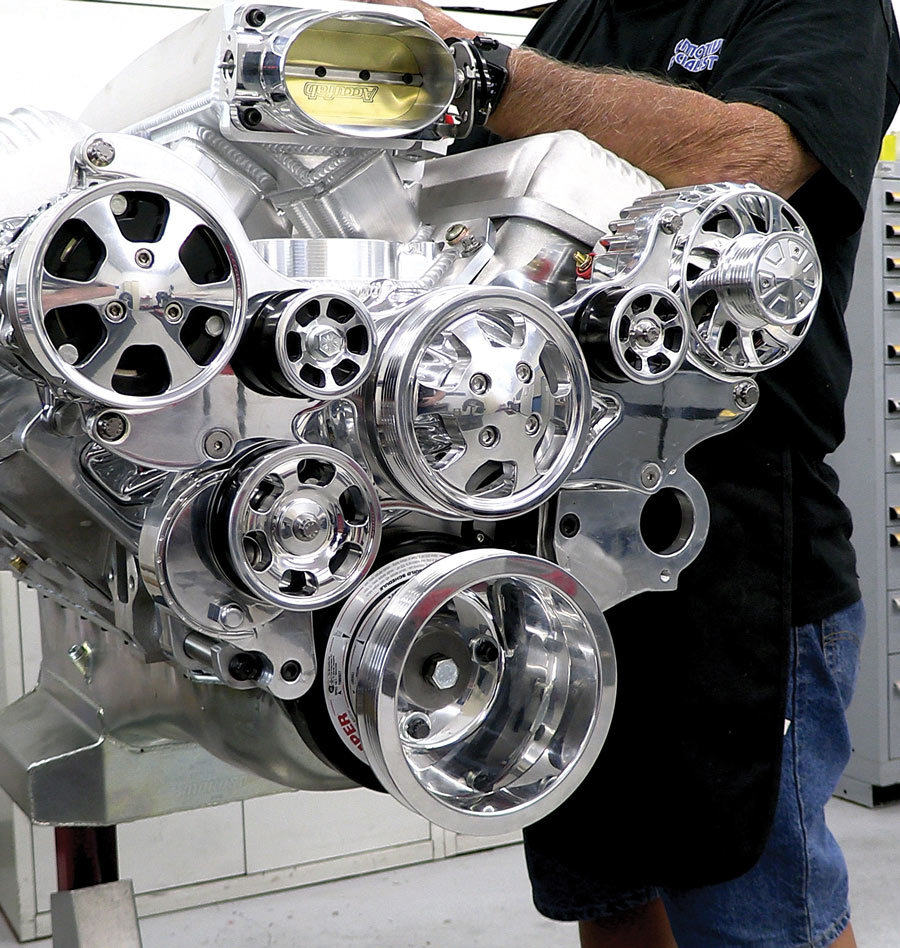

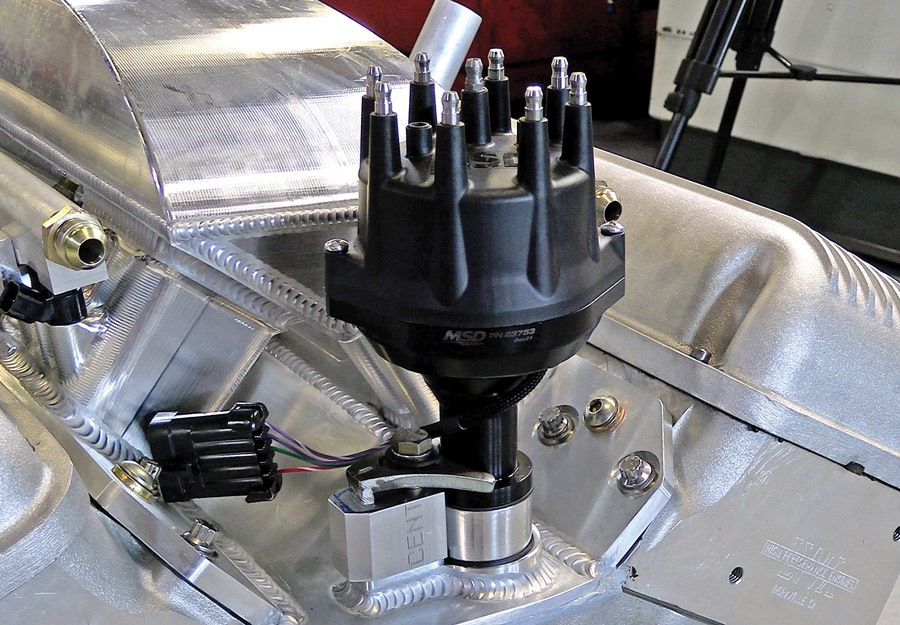

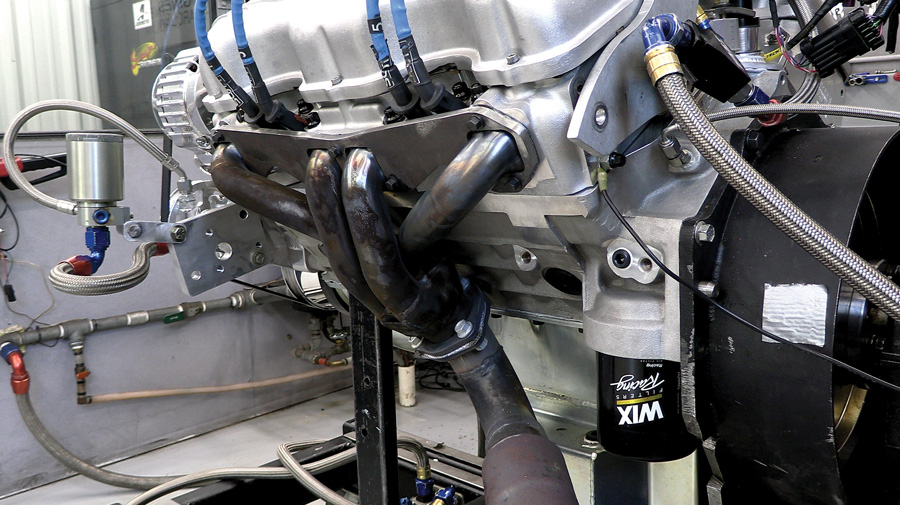

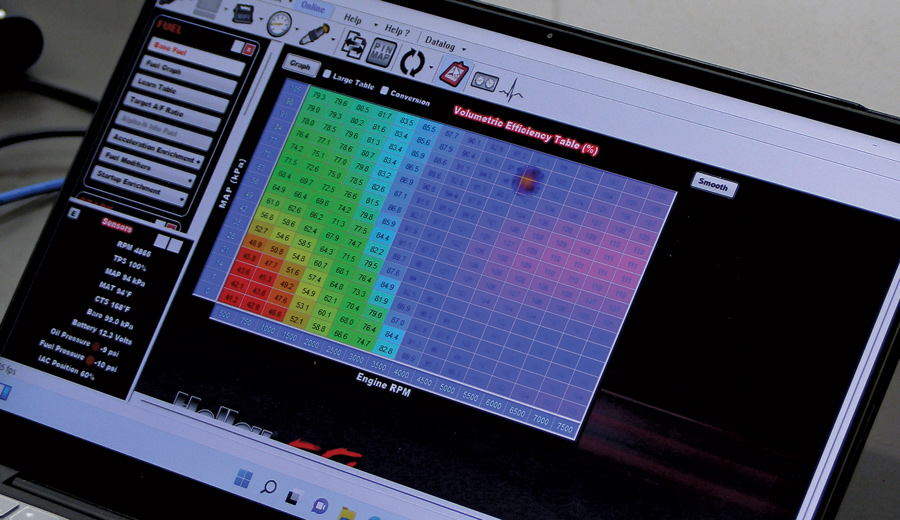

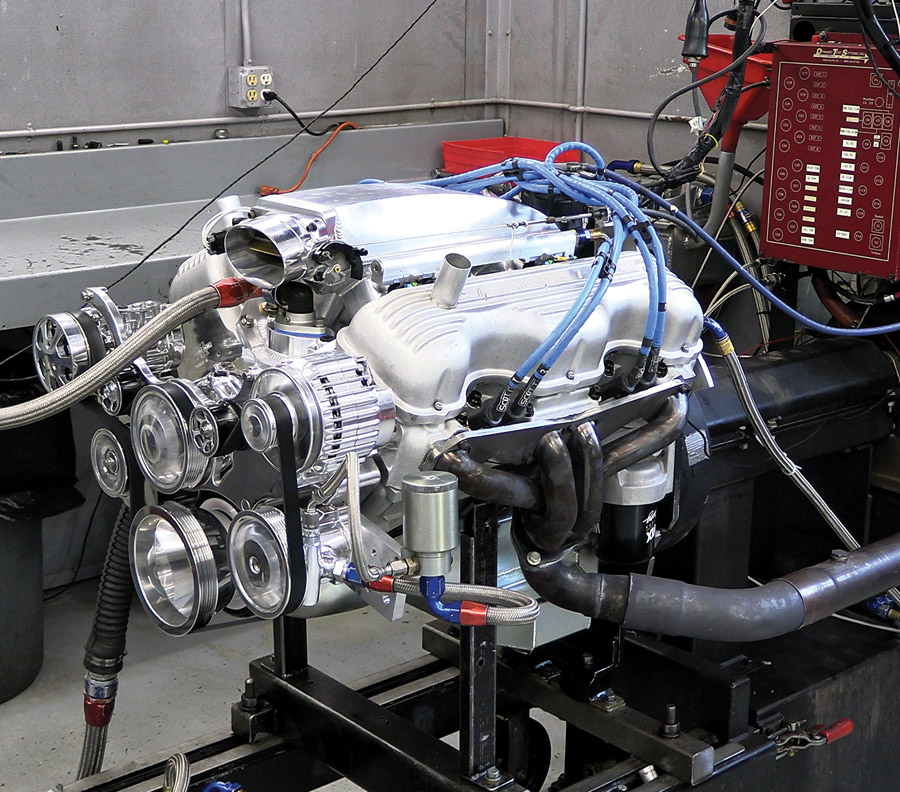

So Dorton put together a recipe for a big-inch, completely modern 409 utilizing absolutely zero OEM components. That means port fuel injection, all-aluminum components, and one seriously sexy intake manifold.

For the build, the car owner and Dorton were able to source an aftermarket 409 block from Bill Mitchell Products and updated cylinder heads from Edelbrock, but there simply was no intake manifold available to fit his needs. So, they worked with Hogan’s Racing Manifolds to come up with a billet unit that’s an absolute jaw-dropper.

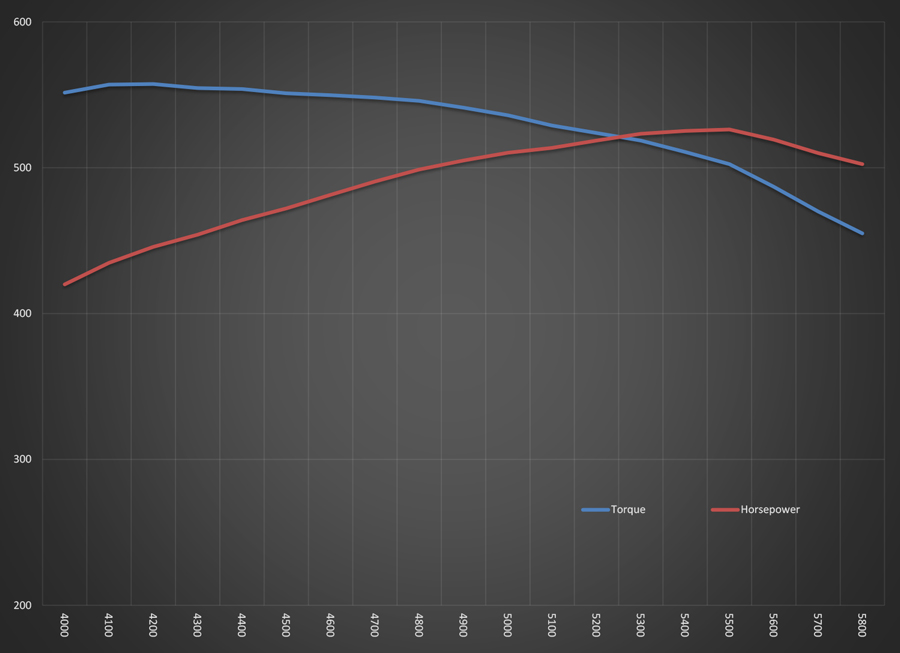

Thankfully, it all came together to run just as great as it looks. This is going into a show car that’s going to get driven. But the owner is looking for good street performance and isn’t planning to take his expensive ride to the dragstrip. So, the cam choice is a bit on the small side for excellent torque right off the jump and good street manners. Still, 557 lb-ft of torque and 526 hp along with modern reliability ain’t nothing to sneeze at and should make this Impala scream like a scalded dog. We can’t wait to see it all come together!