TECH

TECH

Photography by The Author & Courtesy of The Manufacturers

Photography by The Author & Courtesy of The Manufacturers“Man, you absolutely have to have X-pipes–they add 20 hp!”

e’ve all heard the comments and claims. Frankly, neither statement is correct or even close to accurate. So, instead of listening to your sister’s husband’s nephew, let’s dig into a few facts.

We’ll start with the huge claims of horsepower increase and perhaps save you some time. There are small improvements in power with H and X pipes but the gains must underscore the word small. If you’re expecting 20 hp you will be better off looking at a cam swap or headers over stock manifolds because you won’t find more than 1 percent increases with either an H- or an X-pipe.

So why go through the effort? The main reason most people will opt for an H- or an X-pipe has more to do with a change in pitch. This is especially true with an X-pipe. This leads us into more of the details involved with which system might do more for your particular application.

The exhaust noise generated by an internal combustion engine is generally attributed to sound pressure that travels in pulses or waves through the exhaust system. Every time an exhaust valve opens, a pressure wave travels through the primary pipes of the headers into the collector and into the exhaust pipe.

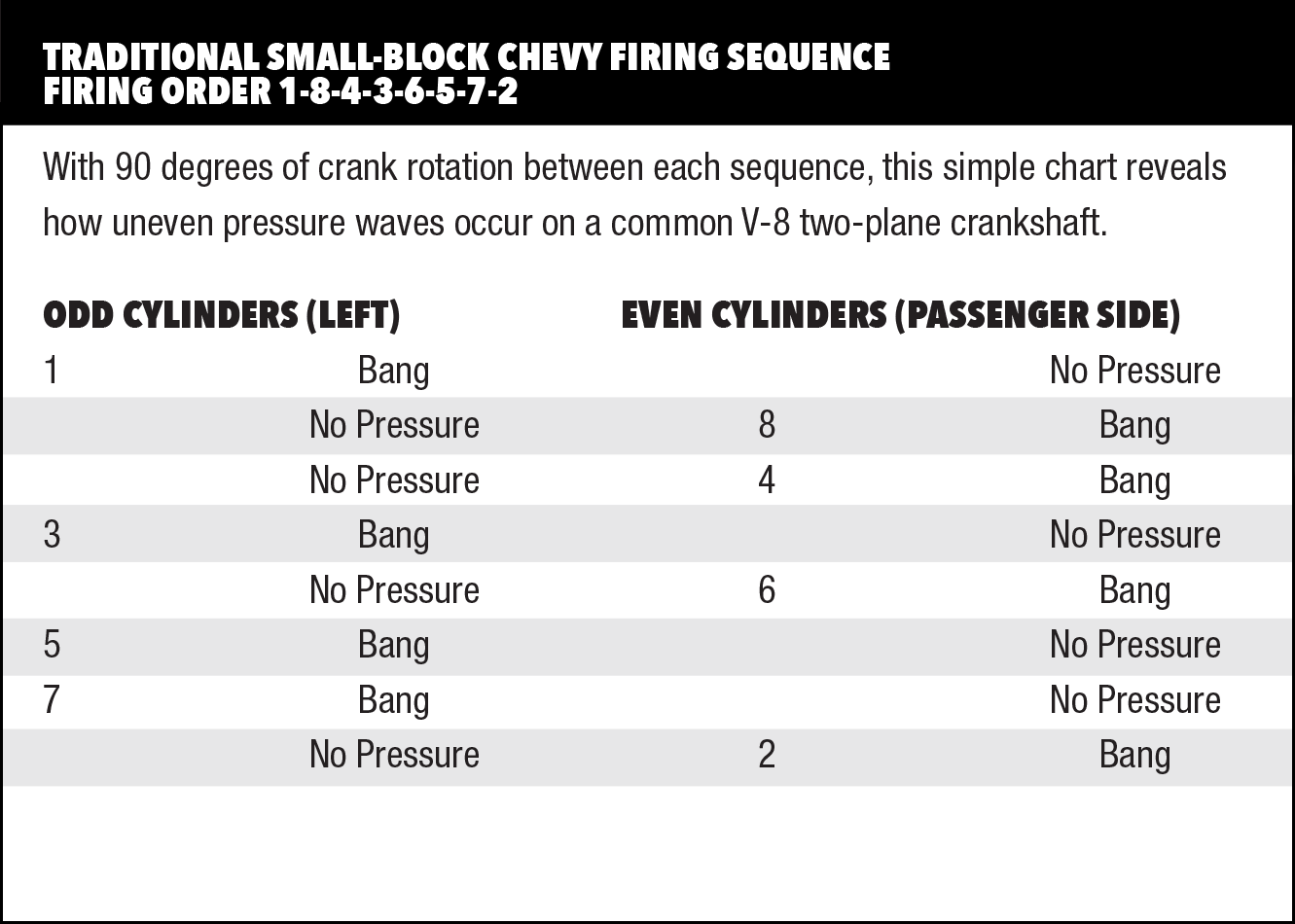

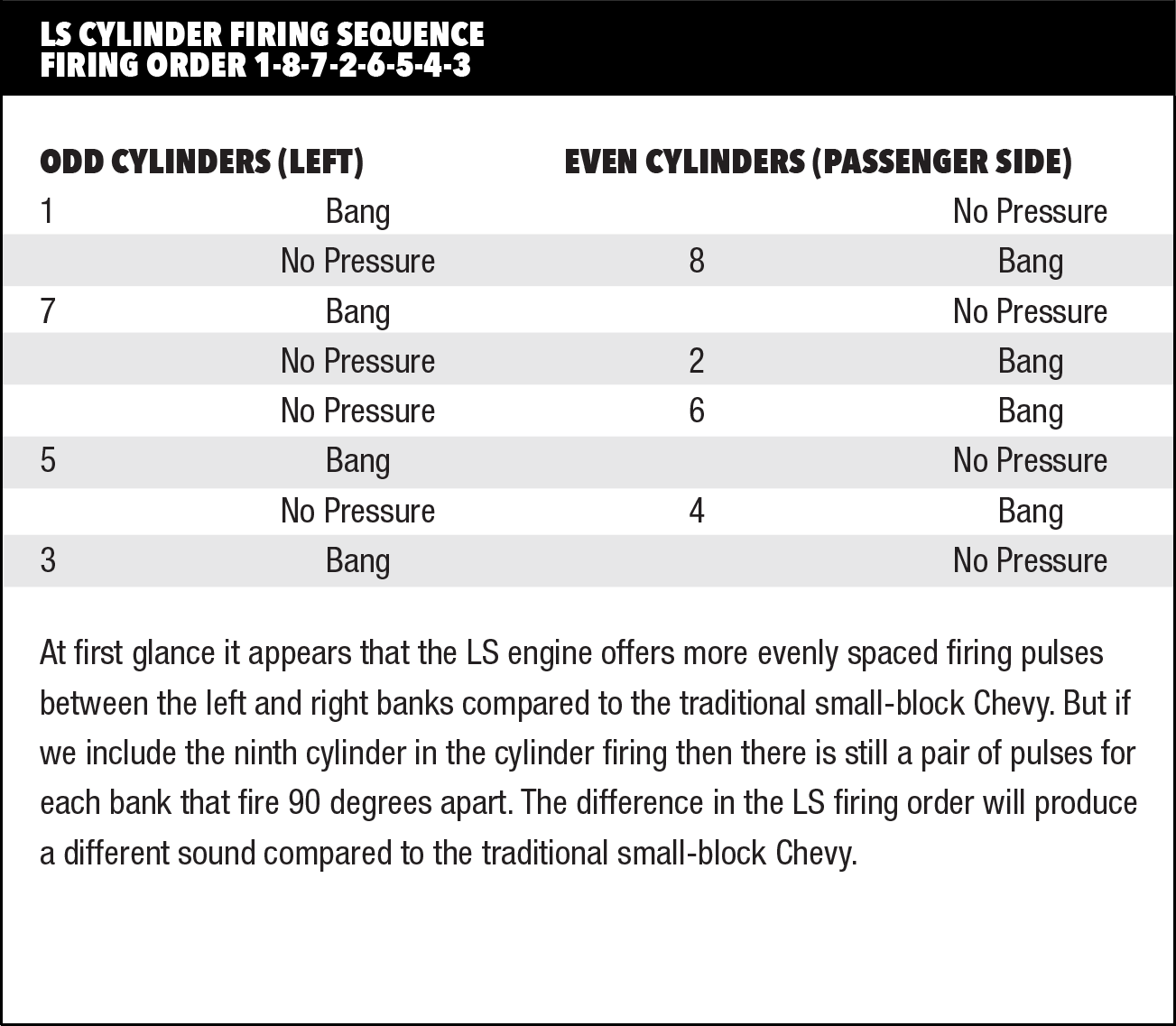

Because of the uneven firing patterns of a typical V-8, these exhaust pulses do not occur evenly. On the left (odd cylinder numbers) side of a small- or big-block Chevy, in the course of a 720-degree complete cycle of the firing order, there is a sequence when there is a 180-degree portion of crank rotation where no cylinder fires on that bank and another 180-degree sequence when two cylinders fire 90 degrees apart.

This uneven pressure spikes occur in both sides of a dual exhaust system and tend to increase backpressure in the separate pipes. If you want to see this for yourself, you can take an ordinary low-pressure gauge that reads 0-5 or 0-10 psi and tap into one exhaust pipe just behind the header collector with a -3 or -4 line to the pressure gauge. At idle, if the pressure gauge is not heavily damped, it will display pressure spikes as the needle bounces irregularly between high and low pressure. This is an indication of the high- and low-pressure pulses occurring in each exhaust pipe.

This indicates how one exhaust pipe between the header collector and the muffler experiences both high- and low-pressure areas. The idea behind an H- or X-pipe is to minimize the pressure spikes on both pipes by adding volume to the exhaust at that location. This contributes to minor improvements in flow.

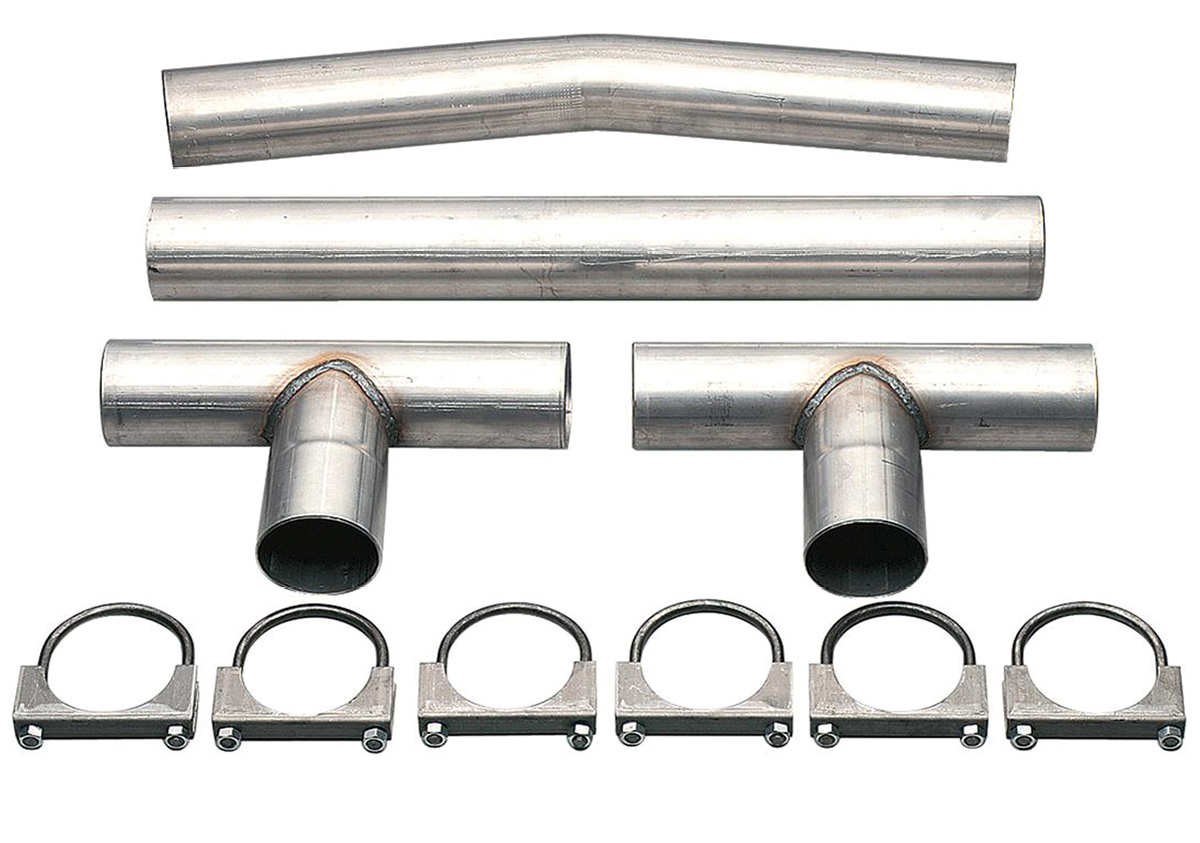

The original H-pipe is a simple 90-degree connector, usually of the same diameter as the exhaust pipe, placed in a suitable position between the two pipes. Don Lindfors, who until recently spent many years with Patriot Exhaust systems, told us that their experiments with H-pipes revealed that often the location of the cross-over pipe could result in slight additional power improvements, but that often this location was very close to (or under) the transmission, which is not only inconvenient but also reduces ground clearance.

The more convenient location for the H-pipe is generally farther back in the system where the exhaust pipes are generally closer together. The length of a typical H-pipe is more often dictated by the distance between the twin exhaust pipes. A longer spread between the pipes will produce a larger volume in the cross-over pipe but is only of minor importance.

The main reason for incorporating an H-pipe in the exhaust system is to alter the tone of the exhaust and also reduce the drone effect present in large exhaust systems at lower engine speeds. This is especially critical if the system is a 3-inch dual system or larger. Our personal experience with a 3-inch dual exhaust system with welded steel mufflers and an H-pipe was in a street car with 3.55:1 gears and a 200-4R overdrive transmission.

At 70 mph, the engine speed was just under 2,000 rpm and the drone produced by this system was exceptionally bad despite the presence of the H-pipe. The ultimate cure was to fit the car with a smaller 2½-inch system with an H-pipe and different mufflers, but even that change did not completely eliminate the drone.

Droning is where the exhaust system creates a resonant frequency at lower engine speeds that creates a low-frequency harmonic that is extremely annoying. There appears to be different frequencies created by each of the main three components in a typical dual exhaust system. The main exhaust pipes are one component, the mufflers are a second, and the third are the tailpipes and tips.

Individually, these components will produce a harmonic at a given engine speed. Depending upon the specific application of exhaust pipe diameter and muffler selection, as we experienced with the 3-inch system, these components can produce a harmonic at lower engine speeds that as one wag put it, “it was like sitting inside Keith Moon’s bass drum at a The Who concert!”

It’s beyond the scope of this story to address ways to alleviate this problem but there is evidence that using a “J-pipe” of specific length (determined using some simple math) welded to each exhaust pipe upstream of the muffler creates a quarter-wave resonator that can usually minimize but often not fully alleviate this problem. The issue with smaller performance cars is there is often little room to fit these specific-length pipes. An H- or X-pipe may help reduce the intensity, but they will not eliminate the drone.

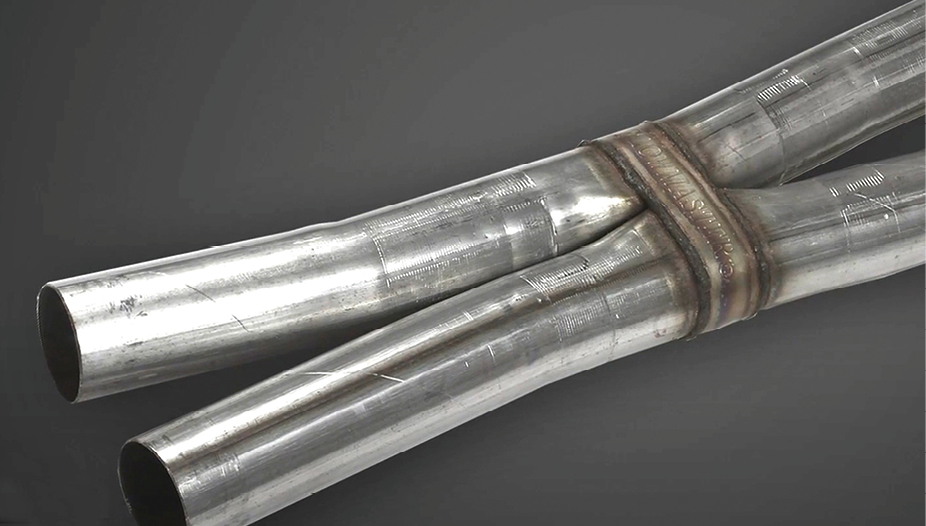

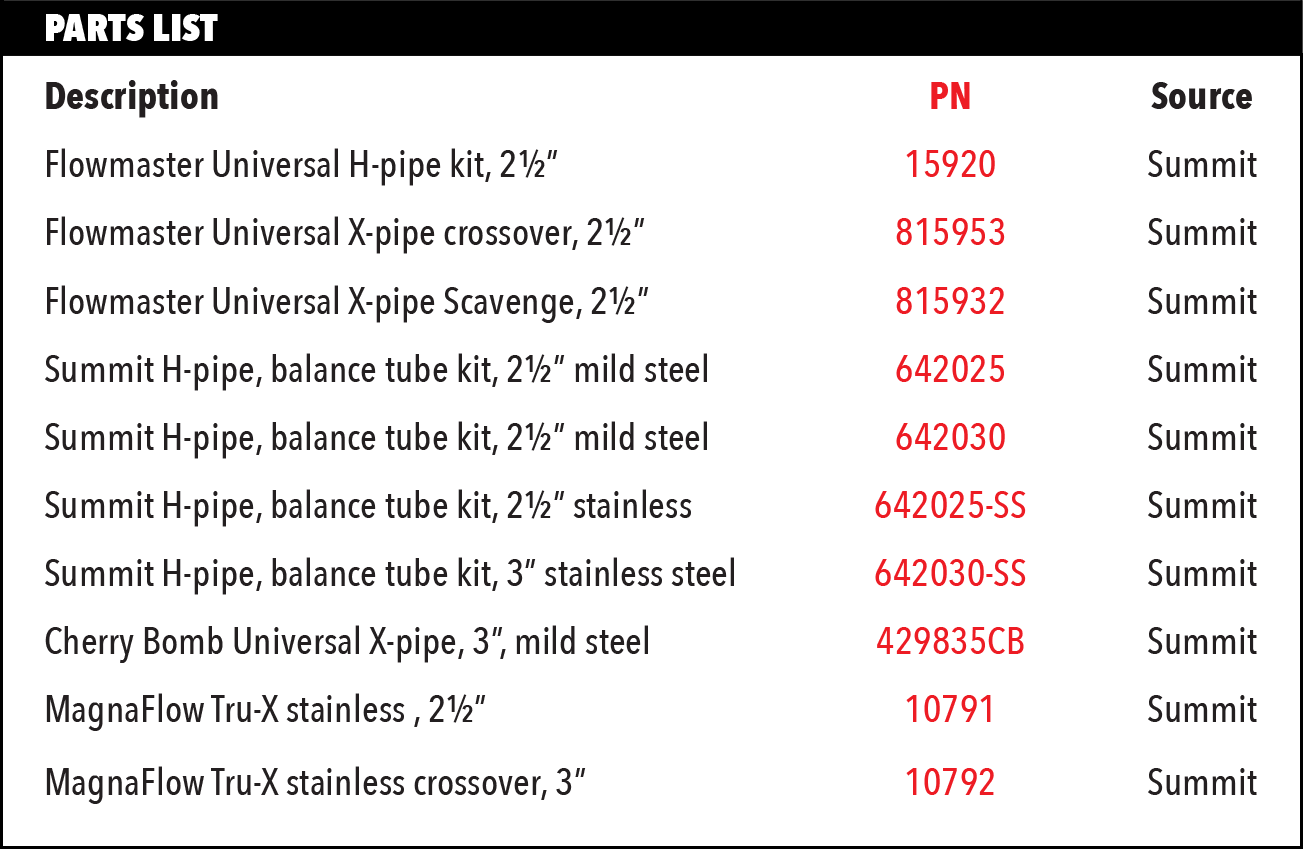

Testing by several exhaust companies and the automotive media has shown that adding an X-pipe offers similar yet minor power advantages but also integrates a different sound quality to the exhaust. Placement of the X-pipe is also dependent on specific applications but for most street cars this will again result in a similar position to the H-pipe just behind the transmission.

Because of the X-pipe’s creation, this can often lead to difficulties in adapting it to an existing dual-exhaust system. The best approach is to purchase a complete system that is created for your particular application. But when this is not possible, a custom system can be created. A good exhaust system shop can produce a very nice system without too much trouble as long as there is sufficient room under the vehicle. This is where trucks have a decided advantage over smaller, more cramped, early muscle cars like a Nova or Camaro. Of course, this entire discussion is predicated on retaining any catalytic converters or other emissions devices for emissions-controlled cars.

Beyond installing an H- or X-pipe crossover into your system this is also a great opportunity to create a system that is easy to service and/or remove. Fully welded exhaust systems are excellent for eliminating leak paths but make it far more difficult to work on the car, such as servicing a transmission or changing a clutch. The classic U-shaped wire muffler clamps crimp the pipes, making them near impossible to separate.

A much better approach is the now-popular stainless steel band clamps. These come in two configurations. The butt clamps align two pipes of the same diameter together. If the pipes are accurately positioned, these clamps do an admirable job of minimizing leaks. The second style is called an overlap clamp that slides over one pipe inside another creating a step. Both band clamps allow easy disassembly of the system and they are reusable.

The ultimate in serviceable connections has to be the stainless steel V-band clamps. These clamps use either flat-face or stepped-face flanges that are welded to the ends of the two connecting pipes. A stainless steel band then aligns these two steel flanges and clamps them together to form a leak-free seal. The flanges can be purchased in either alloy steel or stainless and require professional welding to complete the connection. These clamps are more expensive but offer easy service, making it well worth the initial cost and effort.

We’ve covered quite a bit of technical ground in this piece, and it should be clear by now that there are very few hard and fast rules when it comes to H- and X-pipe crossovers. If you approach these systems as improvements to sound and with less attention to power improvements, you will probably be better satisfied with the results. Exhaust tuning for sound is as much art as science.

SOURCES

SOURCES

SOURCES

SOURCES