Tech

Tech

BY John Jackson, Barry Kluczyk, Wes Allison, Tommy Lee Byrd, John Machaqueiro, Chuck Vranas, Tim Sutton, Scotty Lachenauer & Grant Cox

n the previous issue of All Chevy Performance we connected with a few knowledgeable automotive industry insiders to get their interpretation of a couple common terms us muscle car enthusiasts use on a somewhat regular basis—Restomod and Day Two Resto—and to also inform us of the differences. Hot rodders and muscle car guys/gals tend to have their own definitions, however loose they may be, so we asked longtime magazine editors Jeff Smith, Steve Magnante, and Tony Huntimer to give us their take on what those terms mean to them. It was a fun and enlightening read that gave us a clearer idea of how those terms came about and have evolved over time.

In our second installment of muscle car terminology, we asked our panel to give us the definitions and origins of Pro Touring, Pro Street, and Street Freaks. These terms also lend themselves a bit of latitude and don’t necessarily have a precise definition, but they do require a gauge that we can use when describing the variety of muscle car builds we see on the road and at shows today. Once again, we got some great information of what these terms mean and bit of a history lesson on how they came about.

We always appreciate input from our readers, so feel free to drop an email on this subject to nlicata@inthegaragemedia.com.

Pro Touring

Pro TouringJeff Smith: Here we have some style of traditional boundaries. In around 1999 or so Mark Stielow and I were discussing the next new trend in street cars as the kind of car that he was building. This was during Power Tour. A car that could be quick in the drag race but also turn corners, stop quickly, have fat tires on all four corners, and also be comfortable with A/C and highway manners. I told him if this idea was going to be popular, the trend needed a tag or label like Pro Street. He came up with the term Pro Touring and I put it on the cover of Chevy High Performance magazine and it all took off from there. Neither he nor I started this trend. It was already happening. He gave it a name and I gave it some exposure and the enthusiasts and the industry took it from there. The guys at Popular Hot Rodding recognized the trend but didn’t want to follow and use Pro Touring, so they came up with G Machines. History tells you how far that went. Somewhere in my collection I have a few original Pro Touring decals we made up based on the logo we designed for the Sept. ’00 issue.

What all builders have to be careful to enhance is a common theme for the car. Something that ties it all together. Problems occur when a builder attempts to transition genres, if you will. Trying to tie in parts from Pro Street and Pro Touring generally doesn’t work well. The car becomes confused. Conversely, you look at cars like Scott Sullivan’s “Cheez Whiz” ’55. That car is obviously Pro Street yet look at it in a different light and it almost becomes a Pro Touring car. The best part of it is that over 30 years later this car still attracts attention because of its build quality. It’s less about the parts you use and more about the way you put the car together. And stance; stance is everything.

Steve Magnante: It is generally agreed that our own esteemed staff member Jeff Smith is the man who originally coined the term Pro Touring. He used the term to describe a new breed of vintage cars being rebuilt with an equal emphasis on braking, cornering … and acceleration. Some say the first high-profile Pro Touring–style build arrived in 1987 in the form of father-and-son team Dan and RJ Gottlieb’s ’69 Camaro, which was dubbed “Big Red.” Built to take on the grueling Mexican La Carrera Classica road race, Big Red included a John Lingenfelter–built all-aluminum 540ci big-block, dry-sump oiling, four-wheel discs, big BBS wheels, and a nasty yet tasteful stance.

Though the original Big Red used a carburetor and a non-overdrive Jerico four-speed manual transmission (it was built in 1987 after all), it set the pace for a new breed of street-oriented builds where handling and braking finally caught up with straight-line grunt. So, what separates Pro Touring from Restomod build styles? In a nutshell, Pro Touring was/is less concerned with pleasing the resto crowd. Little attention is paid to achieving a stock look. Pro Tourers are proud of their upgrades, and nothing is hidden from view.

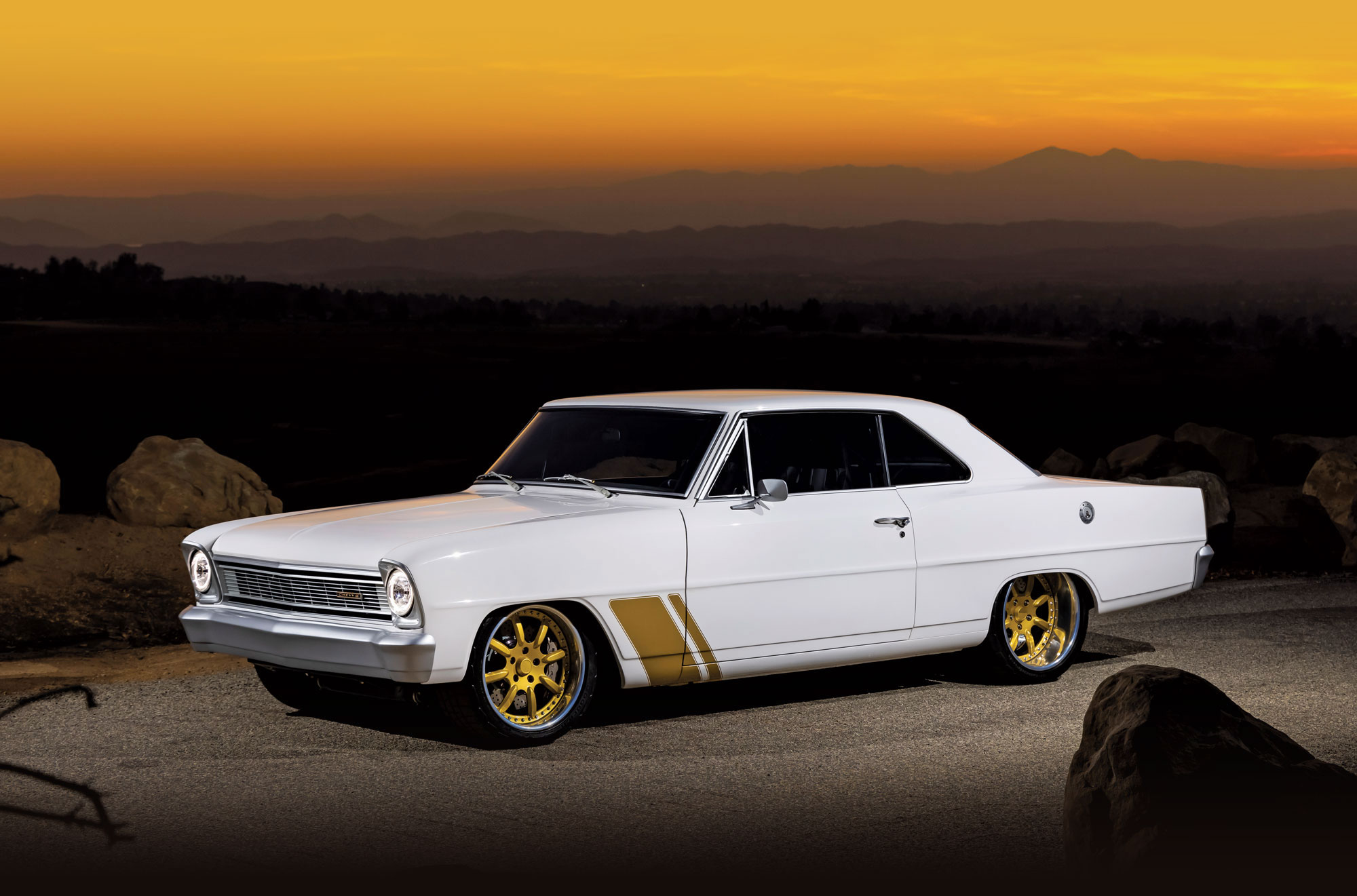

While most Pro Touring builds are based on the typical candidates (Corvette, Nova, Camaro, Chevelle) some brave souls are adapting the vibe to fullsize models and pickup trucks (two-wheel drive, of course). Another Pro Touring influencer is classic Trans Am racing from the “golden age” of 1966-1973. These cars shared the slammed suspension, no-nonsense exotic alloy wheels and aerodynamic aids like chin and trunk spoilers. Hood scoops are notably absent from most Pro Touring builds. The reason is that most Pro Tourers are constructed with low-profile induction systems that don’t need extra hood clearance.

Under a Pro Touring build we can expect to see whatever exotic suspension it takes to deliver a low stance without compromising handling. Aftermarket coilover front and rear suspension kits are popular. Inside, function seems to be the priority with high grip bucket seats, SCCA-legal five-point belts, full instrumentation, and perhaps a rollbar or ’cage for occupant protection and improved vehicle rigidity.

Tony Huntimer: It is used to describe a vehicle that has been modified to handle, drive, and brake better than it did from the factory. It was open to GM, Ford, and Mopar muscle car platforms. If I had to give a year range, it could be a huge range, but it started off with cars from the early ’60s and cut off about the mid ’70s. Pro Touring originally only depended upon platforms that benefited from improved suspension geometry, steering, handling, and braking, as well as better engine performance, overdrive transmissions, more functional seats, and better safety equipment. These days the range of years has really opened up; even some imported vehicles like Datsun Z-cars have even been adopted by the Pro Touring community.

Pro Street

Pro StreetJeff Smith: I was an editor of Car Craft and later Hot Rod during the peak of the Pro Street era so I was there at the height of it all. To me a Pro Street car really only needs oversize, fat tires in the rear with wheeltubs to allow the car to sit right. That, at least to me, is a Pro Street car. Does it need a blower sticking through the hood? Many will say yes and we chose those cars for the cover of the magazine and inside because they were dramatic. But realistically that tall blower makes it near impossible to drive the car safely in traffic since you can’t always see cars coming from your right front, which means you have to drive these cars much more conservatively at the same time that the car’s image is screaming at you to drive it aggressively.

As with all facets of human nature, it’s a common tendency to take what the last guy did and try to top it. That’s what happened to Pro Street. Everybody was trying to top the last guy who built a substantial car. Rick Dobbertin perhaps put the cherry on top with his J2000 in terms of outlandishness. His J2000 at first had no rear springs and then when the Pro Street judges told him he had to add springs, he added six valvesprings that allowed roughly ½ inch of suspension travel. Then Scott Sullivan built the Cheez Whiz ’55 Chevy and drove it across country to prove that you could build a car that won the prestigious Pro Street award at Du Quoin’s Street Machine Nationals and then drive it across country to prove its true street prowess. That was a fun road trip.

Tony Huntimer: My definition of Pro Street comes from my own personal interest, starting in the early ’80s. Basically a street-driven GM, Ford, or Mopar that mimicked what you would see in the NHRA Pro Stock drag racing class: Skinny front runner 3.5-inch-wide front tires. Out back there would be a narrowed, rear axle housing with 12-inch (or wider) tires tucked under stock-appearing quarter-panels … no fender flares. In the beginning, some engines were covered with a large fiberglass hood scoop, but then the builds just started getting outrageous and radical. The engines started getting bigger and taller. They would typically have a supercharger or a tunnel ram sticking up out of the engine compartment. Some builds went full-race style with one-piece fiberglass front ends, aluminum interior panels, wheelie bars, and parachutes. These cars were typically just trailered to car shows and cruised around the fairgrounds, but hardly ever made it out on the street for more than a few minutes.

Scott Sullivan broke the fairgrounds cruiser moniker in 1988 when he and Jeff Smith drove his 10-second Pro Street ’55 Chevy from Dayton, Ohio, to Los Angeles, California. That was a huge deal back then. These days Pro Street cars have evolved enough to be more streetable and race in Street Outlaws and Fastest Street Car competitions.

Street Freak

Street FreakJeff Smith: This is a really old term. Terry Cook used it on the cover of Car Craft in around 1968 describing a dragster with a big-block driving on the street with headlights. Another car from that time period was a Nomad called the Chevado that had an Olds Toronado FWD driveline in the rear and did wheelstands on the street. Now that’s a real street freak.

If we wanted to get into that in modern times it might be something like a tube chassis race car on the street in bare skin and bones.

I had an idea once to try running a street car like an early Chevelle with no front fenders–like a street machine version of a fenderless ’32 Ford where we’d relocate the radiator to the rear of the car with motorcycle headlights mounted low. It would look a little like an old Modified circle track car. That would be a street freak.

Steve Magnante: The Street Freak category arrived long before Pro Touring, Restomod, Day Two, or even Pro Street (a term from about 1979 describing cars configured to resemble NHRA Pro Stockers for the street). Street Freaks originally appeared in the late ’60s and were part of the hot rodding picture until the mid ’70s when the combined effects of the energy crisis and the van craze stole the spotlight.

The first Street Freaks to gain national publicity were seen around 1968 in second-tier car magazines like 1001 Custom and Rod Ideas and Popular Hot Rodding and featured insanely jacked-up front and rear suspensions, chrome-plated axles, fat Indy-profile tires all around, tunnel ram induction, or some equally exotic layout of Hilborn injection or a GMC blower. Bigger magazines like Hot Rod and Car Craft initially ignored the movement but jumped on big time by 1970 with special theme issues titled “Mind Blowers for the Street” (Jan. ’70) and “More Mind Blowers for the Street” (Sept. ’71).

Early on the Street Freak category was a catchall for obsolete race cars hastily modified for quasi-legal street use. Old Gassers, former altered wheelbase, and flip-top Funny Cars all appeared wearing plates. Offshoots included T-buckets with supercharged 427s. In general, if it was outrageous and it wore a license plate it was a Street Freak.

In their prime, owners of well-executed (but not necessarily practical or even functional) Street Freaks could count on plenty of attention from magazines and car show promoters who happily put them on the ISCA national show circuit where thousands of folks bought tickets to see these wild cars in person. Must-have details included wild candy pearl paintjobs with lace, deep metalflake, flames, panel work, pinstriping, and more–often all on the same car. Absurd suspension lifts as much as 3 feet over stock were not uncommon and stacked GMC superchargers (usually hollow inside except for a single carburetor) topped the more popular engine bays.

As expected, the Street Freak movement influenced a percentage of hot rodders who followed suit with home-brewed efforts. But unlike Day Two, Pro Touring, and Restomod builds, the more-show-than-go nature of Street Freaks minimized involvement. That said, the equally impractical Pro Street movement of the ’80s—where huge wheeltubs, massive Mickey Thompson tires, four-link rear suspensions with Heim joints, and coilover shocks—led to the “tubbing and tubing” of thousands of Vegas, Novas, Camaros, and Chevelles.

This writer is old enough to recall the Pro Street movement firsthand. I was horrified when a pal violated his rust-free ’67 Camaro with a four-link suspension kit, radically narrowed Ford 9-inch rear axle and big tin tubs. The resulting Pro Street Camaro was an ill-handling mistake. Today, reproduction sheetmetal companies are making a well-deserved killing selling replacement trunk floor and wheelhouse patch panels to correct the surgery. Likewise, most Street Freaks were so impractical on a daily basis there’s little threat of a resurgence.

Tony Humtimer: My take on the Street Freak is a badass car that mixes different build styles that don’t really fit the mold of one build style. A Street Freak might be a ’67 Camaro that’s all jacked up with a gasser-style straight axle up front with some super-wide tires out back sticking out past the fender openings … possibly with fender flares on the rear quarter-panels. Or a ’70 Mach 1 with IMSA flares and vintage super-wide 15-inch-diameter mag wheels on all four corners and then top if off with some side-exit exhaust for fun!