TECH

TECH

Photography by Jeff Smith

Photography by Jeff Smithhere comes a time when every gearhead wants more from their engine. Sure, we vowed we’d leave it stock. Then we threw the entire catalog of bolt-on parts at it. And still, we want more. The high-flow intake manifold helped. The big-tube headers did too. But when it comes to truly awakening an engine’s power potential, it’s time for a camshaft.

If the cylinder heads are considered the lungs of the engine, the camshaft is undoubtedly its brain. Not only will it determine how much power and torque an engine will make, it controls at what point in the powerband they occur. Camshaft choice will also dictate idle quality, piston-to-valve clearance, and many more variables. That means choosing the right camshaft for your application is immensely important.

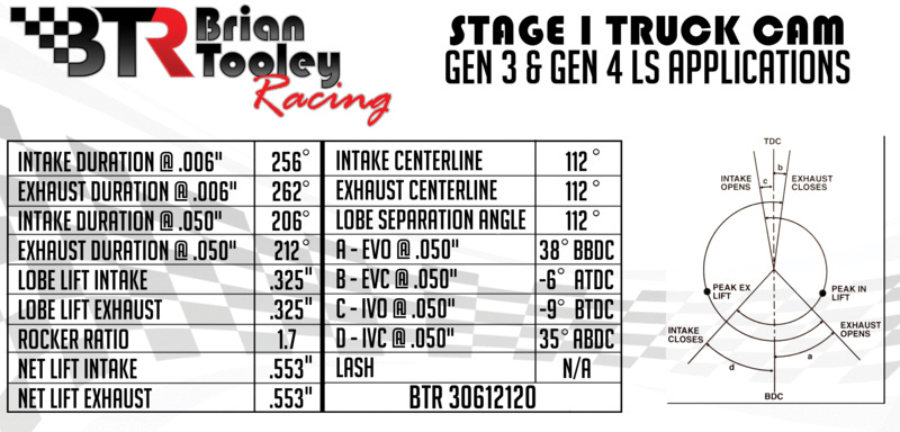

Due to the unfailing popularity of LS engines, from late-model OEM vehicles to street rods to retro-swapped muscle cars it seemed a natural platform to focus on when setting some guidelines on just how to pick one. For some expert advice on the subject we turned to Brian Tooley of Brian Tooley Racing (BTR) who specializes in LS camshafts, springs, and other performance valvetrain hardware.

For the sake of this story, let’s assume you’ve never touched a cam. The cam card might as well be Greek, and you have no idea what your first step should be. That’s OK and the best thing to do is collect the information within your control. What LS-based engine do you have? What car is it in? What do you plan to do with that car? Is it a cruiser? A dragstrip bruiser? Or, does it pull your fishing boat to the lake. While seemingly superficial questions, they actually give a seasoned cam tech a good deal of info to steer you in the right direction.

“In my opinion the most important consideration is making sure you purchase a cam designed specifically for your application and how you intend to drive your vehicle,” Tooley says. “Customers need to accurately communicate exactly what the application is. Vehicle weight, converter size, and so on are all extremely important.”

Nail the basic information first, then move onto the more detailed specs.

Manufacturers like Tooley also offer an approach that mitigates the intimidation factor of cam selection that comes in the form of simple stage kits. “The smallest stages can be used with stock converters and the largest stages generally require aftermarket stall converters and driveability takes a hit.”

This might seem strange but it actually plays a major role in power production. For example, a street/strip cam might close anywhere between 30 degrees ABDC (after bottom dead center) to 75 degrees-ish ABDC, depending on its specs. The reason this happens is that the air and fuel charge that flows through the intake ports at nearly supersonic speeds has mass. At high rpm, that mass and high-speed create a moment that allows it to continue flowing into the cylinder even as the piston is rising, which helps maximize cylinder filling and power production. However, a large cam with a long duration and late intake valve closing point can significantly rob power and torque production at low rpm by allowing a significant portion of the inlet charge (which has less momentum at low rpm) to escape from the cylinder back into the intake manifold. This is known as reversion. On the exhaust side, a long duration tends to open the exhaust valve deeper into the power stroke, which also hurts low-speed power and torque.

Choosing a cam sized to produce power and torque where you realistically need it will always deliver better results than aiming for an arbitrary peak number. Libraries can be—and have been—filled with information about internal combustion theory and this is only the tip of the iceberg.

Avoiding this issue is simple as the maximum specs have been thoroughly scienced out. Tooley says that in general, most LS applications [with stock pistons] are limited to around the following IVO (intake valve opening):

• Gen III-IV (15-degree head) engines can tolerate 9 BTDC @ 0.050

• LS7 (12-degree head) engines at least 15-degrees BTDC @ 0.050

• LS3 (and square port heads) are 8 degrees BTDC @ 0.050

• Gen V 6.2 is 5 degrees BTDC @ 0.050

• Gen V 5.3 is 2 degrees BTDC @ 0.050

“We sell centrifugal supercharged cams and positive displacement supercharged cams,” he says. “The superchargers themselves generate power curves that are completely opposite from each other. Centrifugal superchargers tend to make less midrange torque but offer tremendous top-end horsepower, where the positive displacement superchargers tend to make great midrange torque but struggle with making great top-end horsepower. Because of this we design those supercharged cams completely differently.”

Camshafts for blowers and turbos tend to have wider lobe separation angles (LSA), which in layman’s terms are a rough estimate of intake valve/exhaust valve overlap. An NA engine utilizes overlap, when combined with low pressure pulses in the exhaust, to create a scavenging effect that helps to pull spent exhaust gases out of the cylinder and fresh air/fuel mixture in. In a forced-induction application, the power adder (supercharger or turbo) is doing that work and less overlap and is required. This is why you tend to see blower, turbo, and even nitrous cams with slightly wider LSA numbers when compared to an NA grind.

“We have NSR (No Springs Required) truck cams that are 0.482-inch lift and can use stock truck springs and pushrods,” Tooley says. “We also have 0.552-inch lift truck cams that need LS6-style springs but can use stock pushrods. All of our cams that are over 0.600-inch lift require aftermarket springs and pushrods.”

When moving to a higher lift camshaft, such as the 0.600-inch grinds mentioned above, a better spring is almost always a requirement to adequately control the valve and prevent the new, more-aggressive cam lobe from floating (more accurately “bouncing”) the valves at higher rpm. When that happens, the valve is not able to return to its seat and fully close at the intended time and power will immediately drop off. This loss of valve control is very hard on the valvetrain and can cause damage if it repeatedly occurs.

“If you have an application that a specific camshaft vendor has spent weeks or months developing camshafts for on the engine dyno and Spintron, don’t trust someone without those tools to design you a better ‘custom’ cam, it’s just not going to happen,” Tooley says. “The level of competition in the camshaft market has never been greater, and the customer who is doing his research into which camshaft manufacturer is doing the most research on their specific application is going to benefit greatly.”

SOURCE

SOURCE