TECH

TECH

Invaluable Tips For Your LS

We Spoke With Several Top Engine Builders and Tuners to Help Solve the Biggest Headaches LS Owners Suffer

Images by Jeff Huneycutt

Images by Jeff Huneycuttere at All Chevy Performance we don’t have to waste breath explaining to you just how important the Chevrolet LS engine is to the world of automotive performance. When it comes to the legacy of horsepower, the LS is the greatest thing since … well … the original small-block Chevrolet.

But that doesn’t mean the LS series of engines is without its idiosyncrasies. No engine is. You can, however, with a smart plan, almost always build an LS that perfectly suits your needs. The only problem is you need to know ahead of time what weaknesses you need to work around, and that knowledge usually only comes with years of hard-won experience.

The good news is we’re going to help you skip right past all those years of learning lessons the hard way. With the help of some of the very best LS engine builders and tuners we could find, we’ve put together a list of tips to help you avoid some of the most common pitfalls when putting together an LS combo. Some are specific to the engine itself and others concern support systems, like fuel. We’ve skipped over the basics like “don’t forget the barbell” or “make sure you clean everything first” for a little more advanced stuff—and we bet there’s a few in here you’ve never heard before.

Special thanks goes to Automotive Specialists, Gibbons Motorsports, Heintz Racing, Prestige Motorsports, and SS LSX Tuning and Performance.

One thing we heard mentioned is most LS cam grinds have a wide lobe separation. This allows you to have big duration numbers without too much overlap, which can help fuel efficiency and limit unburnt fuel making it into the exhaust pipe. But it can also tend to make the horsepower curve a bit peaky. By tightening up the lobe separation on the cam grind to 112 or 114 degrees you can often widen the powerband a bit and improve the overall driving experience. Engines like the LS3 have no trouble making a big power number, but improving the crispness of the throttle when you get on the gas is always a good thing.

The cathedral port design is great at maintaining intake port velocity, which always helps low-end torque. Stock cathedral port heads can also be found with smaller combustion chambers than equivalent stock rectangular port heads, so you can raise the compression ratio by as much as a point. So, if you are building a smaller engine, maybe based on a 5.3- or 4.8L block, and you aren’t planning to boost it to the moon, you can often find more success getting good low-end torque and a lively throttle pedal with a cathedral port head. Since they aren’t usually as sought after, they’re easier to find used anyway.

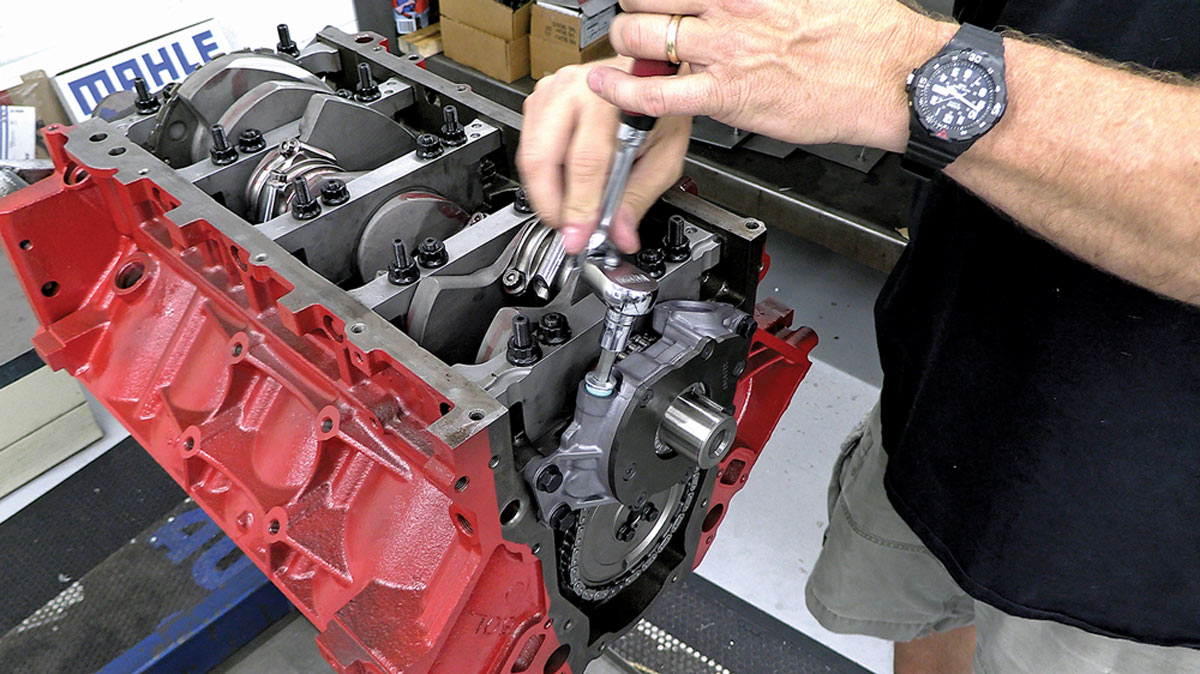

A lot of people want to do the same thing with LS engines. But the LS oil pump is driven off the crankshaft and not the cam, so it is spinning twice as fast. The problem is that matching a high-volume oil pump with a stock oil pan can cause problems. If you are puttering around town you’ll be fine, but when you are pushing the rpm higher in the range, the high-volume oil pump can pull all the oil out of the pan and pump it into the lifter valley before the oil has a chance to drain back down. The engine builders we spoke with said in the right situations it can happen in a matter of seconds.

Has this happened to you? After all, you can briefly lose oil to the bearings and do damage without grenading your engine. One easy way to tell is to take a look at your bearings during a rebuild. If the main bearings have a golden hue, that’s a good sign of loss of oil pressure. Same thing if the main journals of your crank have taken on a black tone.

So, what do you do about it? If you want to run a high-volume oil pump, switch to an oil pan with a bigger sump for more volume, but if you are in a situation where you can’t or don’t want to change your oil pan, use a high-pressure oil pump instead. A popular option among the engine builders we spoke with is a Melling high-pressure pump (PN 102950). It allows you to adjust the pressure by swapping out the bypass spring from a selection included with the pump.

The problem with the smaller 5/8-inch plug is that it only provides about 0.001 inch of crush. It’s enough to hold the plug in place in most conditions, but not enough to guarantee it won’t come out if the oil pressure is high and the block gets hot. It sits directly behind the timing chain cover. So, if you are using a stock cover it can only back out the thickness of the timing cover gasket. But that’s enough to create an oil leak, and since this gallery plug is on the pressure side of the engine it can drain off valuable oil pressure. On some aftermarket timing covers, especially billet pieces, it is possible that the wrong size plug can be pushed all the way out, causing you to lose oil pressure entirely.

The solution to this one is simple: Just make sure you have the correct 41/64-inch plug and continue with your build.

But that also means you can very quickly surpass the stock fuel system’s ability to move enough fuel to the engine when it needs it. There are several options when it comes to upgrading a fuel system, but one you want to be wary of is the so-called fuel pump boosters or “boost-a-pumps.” These work by throwing extra voltage to the existing fuel pump, forcing it to move more fuel. This works for a time, but it significantly shortens the life of the pump by forcing it to work well beyond its design parameters. Essentially, it’s just a Band-Aid.

Fuel pump boosters are often thrown into those “everything’s included” supercharger kits for LS engines because they’re cheaper than proper high-flow fuel pumps. But if you are going to upgrade your ride with a supercharger, we’d suggest doing it right by properly upgrading your fuel system. Adding a pump booster will work for a while, but it only increases the chance of you getting stuck on the side of the road with a burned-out fuel pump.

Instead, consider going ahead and dropping the fuel tank to install a quality high-flow fuel pump. Or you can install an auxiliary pump, but that usually requires drilling a hole in your fuel tank and also adds complexity to the overall fuel system.

While we’re at it, when adding big power through a supercharger or turbos, make sure you are also upgrading to quality injectors that can handle the higher fuel flow requirements. If you are switching to E85, the drastically different stoichiometric ratios (gasoline is 14.7 parts air to one part fuel while E85 is just 9.8:1) means you are going to be moving lots more fuel, so you likely will also want to go with larger-diameter fuel lines.

That sound doesn’t come naturally with a modern engine with port fuel injection. But cam designers can replicate it with the right combo of extra-long duration on the exhaust lobes and just the right amount of overlap. We admit it does sound pretty good, and you can see clips of engines with these cams all over social media.

The problem is these cams are designed for sound first. They will even make a good number on the dyno, but the low- and midrange certainly suffers. And if you have a street car, it is the bottom third of your tachometer where you spend 90 percent of your time. We had one engine tuner tell us he’s removed several of these cams from cars and trucks powered by LS engines over the last few years. The owners fell in love with the idea of that rumble at idle and purchased a cam for their LS. But once the cam was in, they hated how the car drove and had it taken back out.

We’re not saying the “chop” cams are bad, just that there are always trade-offs. Some are obviously better than others at making a great rumble without sacrificing too much performance, but you’re just not going to get both. If you’ve just got to have that growl and are willing to sacrifice a little bit of driveability, then fine. But if performance is your primary motivator, you may want to stay away.

It seems back in the early days GM tried an interesting quirk in the manufacturing process where they installed the cam bearings and then honed the cam bore for straightness. Maybe it was for manufacturing efficiency and saved a few pennies per block, we’re not sure, but it can cause big problems for you.

If you are planning a rebuild with one of these early blocks, it is definitely in your best interest not to knock out and replace the cam bearings unless you absolutely have to. In almost every other block where the cam bores have been align honed before the bearings were installed, you can replace the cam bearings no problem. But on these early LS engines where the honing was done with the cam bearings in place, just knocking in a new set of bearings will mean the cam will be tight in the mis-aligned bores. And few machine shops are set up to hone blocks in this manner without major aggravations. So, it’s going to cost you.

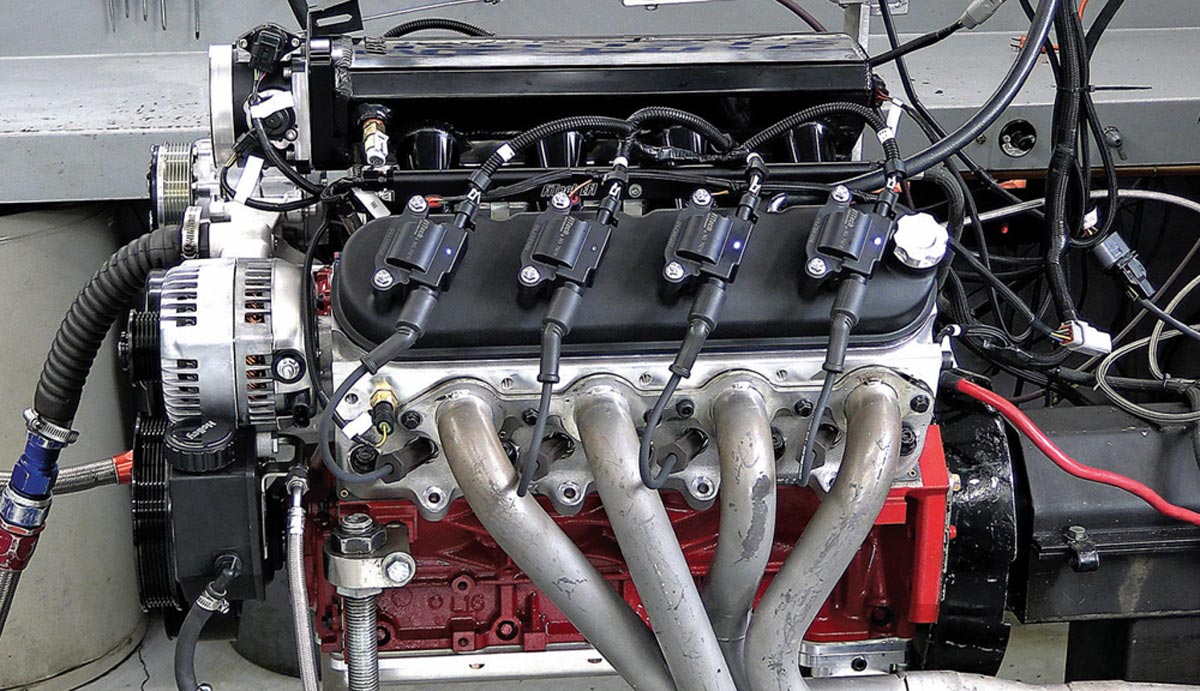

Each coil is close to its respective coil on an LS engine, but it isn’t coil-on-plug. So, there’s a short plug wire, between 8.5 to 10 inches depending on model, connecting the coil to its spark plug. These wires route between the exhaust ports on the cylinder heads. When adding a header, they will sometimes be able to touch the hot exhaust tubes. This really depends on the header design, but a lot of guys will simply add a little protection by sliding on a set of plug wire insulating sleeves.

These sleeves do a great job of protecting plug wires if they briefly touch a hot header tube. But the key word here is “briefly.” It doesn’t mean they will protect the plug wire forever. One tuner we spoke with told us they’ve run into the issue enough times that whenever a customer brings their car in because it is running poorly, the first thing they do is remove all the insulator sleeves to inspect the plug wires. The insulator will delay the heat getting to the wire, but over time it can still get hot enough to do damage. The tuner found that guys will install the plug wire insulators and then let them flop wherever they wanted. Then when the plug wire gets burned after extended contact with the header tube, the insulator hides the damage so you can see it with a quick visual inspection.

The lesson here is to spend a little time making sure your plug wires are routed or secured so that they cannot touch your header tubes. If you want to run insulators, that’s fine, just don’t use them as a crutch for poor routing habits.

For this one we are including the iron truck blocks in the family, the 5.3- and the 4.8L engines because they are also affected. In the less performance-oriented LS engines the oil filter mount in the oil pan includes an oil filter bypass. This is a spring-loaded valve that opens up when the oil pressure gets too high and allows oil to bypass the oil filter.

The purpose of the bypass is to protect the engine from owners who may not change their oil and filter as often as they should. If the oil filter gets clogged, the bypass will open up to ensure that the bearings still get oil, even if it hasn’t been filtered. And the facts back this up because the bypass can’t be found on the high-performance LS engines like the LS7 or LSA. It is also usually nowhere to be seen on any aftermarket oil pans.

So, if you are building a big-power LS, make sure the oil filter bypass is deleted. That’s because if you run a high-pressure oil pump like we recommended earlier in this article or making extended high-rpm runs, the oil bypass can open up and send unfiltered oil through your engine. Since you are changing your oil and keeping a fresh oil filter on there, too, you don’t want the bypass activating. This is easy enough to do, just replace the bypass with a screw-in plug that is available from any number of vendors. You will need to pull the oil pan to do it, but if you are making big upgrades to your engine the bypass is worth it.

SOURCES

SOURCES