TECH

TECH

Images by The Author

Images by The Authorf you ever feel the need to enliven a conversation among gearheads during a bench racing session, merely float engine oil into the discussion and then sit back and watch the fireworks shoot around the room. The problem with all the resulting banter is that there are always plenty of opinions offered but a discouraging lack of facts. So, we’re going to enhance this discussion with 11 facts about engine oil along with additional tidbits of which you may not be aware that you will find useful for your current or next engine project.

Everyone knows that conventional engine oil is refined from crude oil. But not all conventional oil is the same. Pennsylvania crude is much different from the black stuff that originates in Texas or Oklahoma. But that aside, conventional oil is made up of a complex blend of multi-chained hydrocarbons. Imagine a tree trunk with lots of smaller branches projecting in various directions.

Synthetic oil can begin as conventional crude oil, or it can be processed from different hydrocarbon chains like natural gas. Synthetics are chemically processed to eliminate most if not all of those random branches. The result is a designed hydrocarbon chain that is both more thermally stable and offers a much higher viscosity index.

This synthetic process increases the price of this oil while offering multiple advantages. Physics dictates that any oil will lose viscosity when heated. The advantage of synthetic oil is that it tends to maintain its viscosity over a wider temperature range than conventional oil. This gives synthetics their higher viscosity index.

Oxidation is the process of oil breaking down and losing important properties. The oxidation rate of oil doubles for every 18 degrees F change in oil temperature. This becomes a real issue for conventional oil above 250 degrees F. Synthetics generally can tolerate higher temperatures approaching 300 degrees F without significant breakdown.

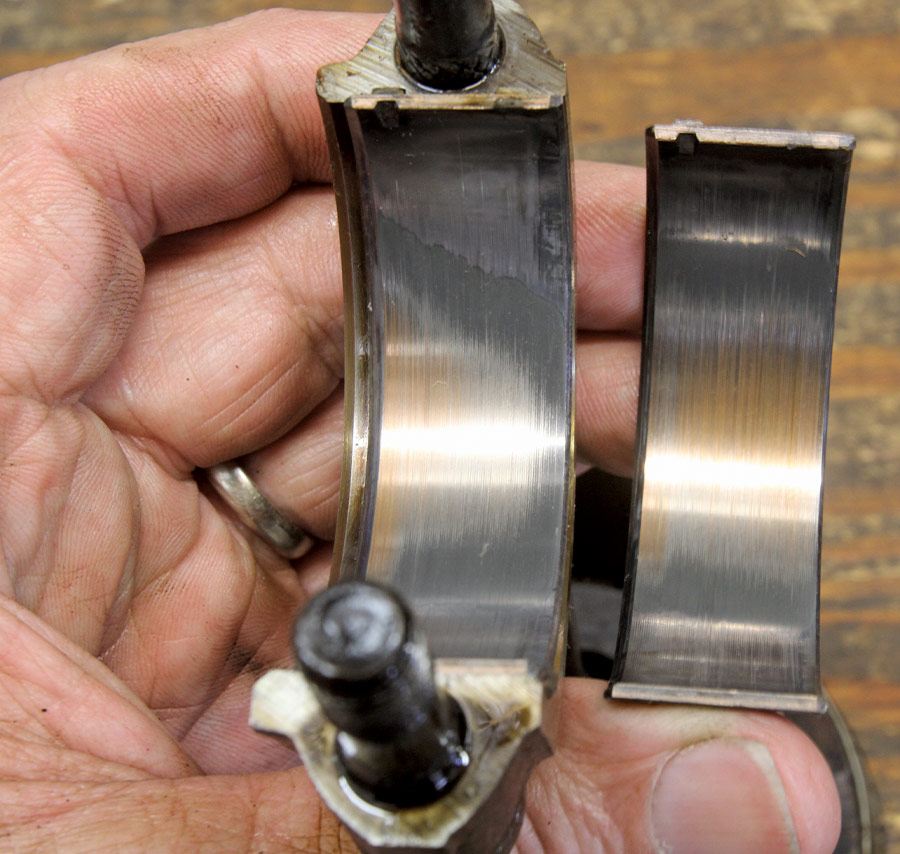

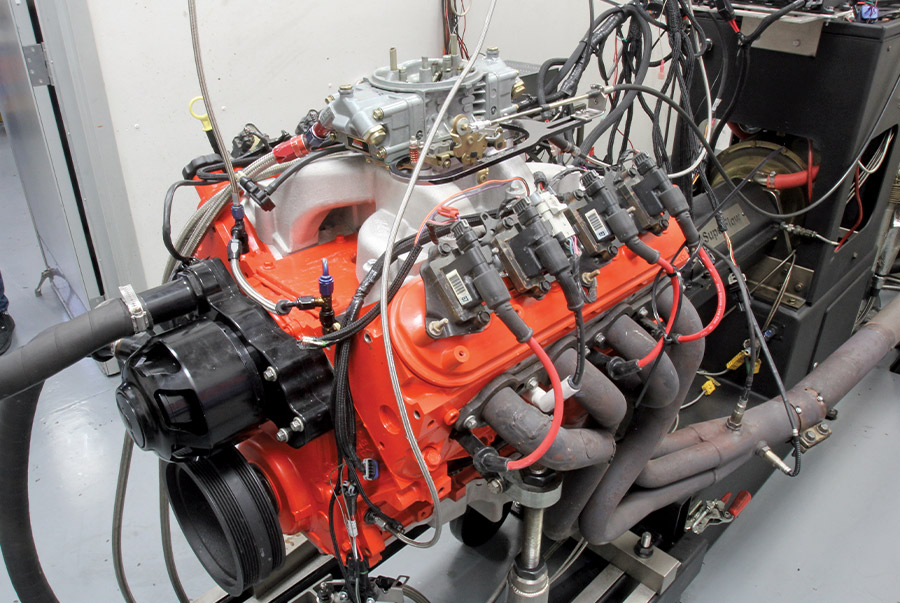

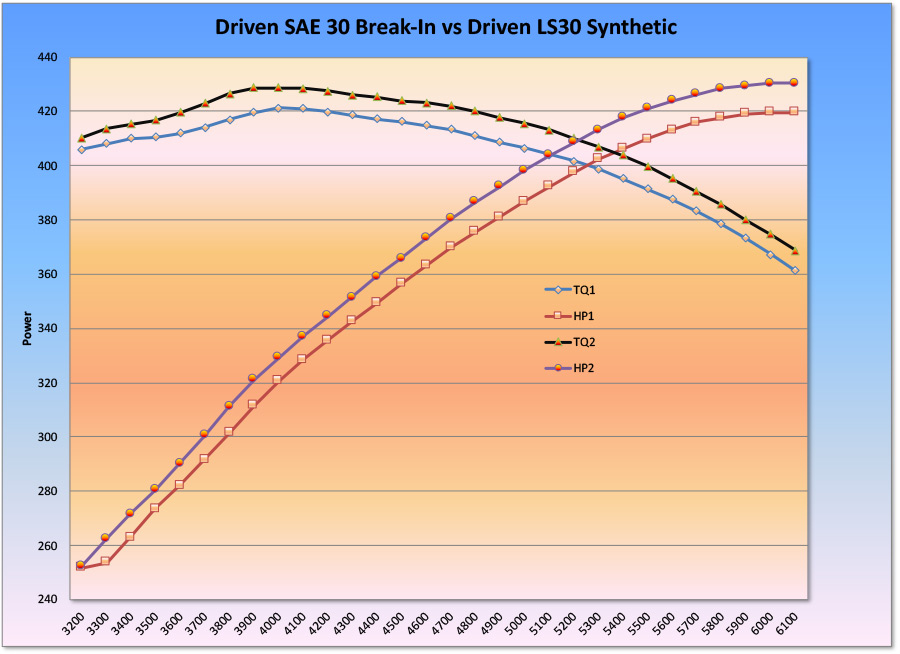

We witnessed a synthetic versus conventional oil test performed by Lake Speed Jr. several years ago that revealed an improvement in bearing wear under a harsh, high-load/low-rpm test on a 383ci small-block Chevy. The test revealed measurably reduced bearing wear when a synthetic oil was subjected to high oil temperature and high load compared to a conventional oil of the same viscosity. While perhaps not necessary for a mild street engine that might not see this kind of abuse, race engines can certainly benefit from improved wear protection offered by synthetics.

The main advantage to a blend is that this can enhance performance through improved oxidation resistance as well as better thermal stability both at low and high oil temperatures. As one example, Driven’s GP-1 is a synthetic blend with which we’ve had good experience. It combines high-quality Pennsylvania grade conventional base oil with a synthetic base stock to enhance its performance. Other quality blends include several viscosity options available through AMSOIL.

Our friend Lake Speed Jr. performed a test several years ago where Driven’s GP-1 was tested on the dyno against a pure conventional oil of the same viscosity. The test found single-digit horsepower gains while also reducing the oil temperature through reduced friction.

Essentially it is like playing a game where you don’t know all the rules and you have to guess at the results. As an example, Speed says that introducing additives into your oil is like pretending to be a backyard chemist. Unlike API-rated engine oil with published standards, there are no standards for engine oil additives. The most popular, of course, are the bottles of zinc and phosphorous (often referred to as ZDDP). His testing of one popular additive found 2,749 parts per million (ppm) of phosphorous and 2,037 ppm of zinc.

This combination of ZDDP represents a total concentration of these compounds of over 4,700 ppm. The problem is that too much ZDDP can be harmful to internal engine components by increasing the acidity level of the oil. A proper concentration of ZDDP closer to 1,200 to 1,500 ppm reduces wear on highly loaded components like flat-tappet lifters and cam lobes. But excess levels of ZDDP can actually increase the acid count of the oil while simultaneously increasing wear. To summarize, Speed says that if you are mixing additives with your oil, you are using the wrong oil.

The main reason for reduced detergent levels in race oil is because detergents tend to strip away the layer of ZDDP protection in high-pressure locations. This is also why break-in oil is generally created with extremely low levels of detergents so that the ZDDP can quickly create the protection layer without being stripped away by the detergents.

So, if you choose to use race oil like Valvoline VR1 for example, it’s recommended that you change the oil much more frequently compared to street oil that includes higher levels of detergents. Examples of boutique oil with higher levels of ZDDP but that also contain detergents for street use include Comp’s Muscle Car oil, AMSOIL’s Z-Rod synthetic, Lucas Hot Rod & Classic, Driven GP-1, and others.

Several companies, including AMSOIL, Blackstone, and SPEEDiagnostix, offer this service. We’ve listed their contact information at the end of this story. Most services offer priority mailing with quick email results that are often delivered within a week.

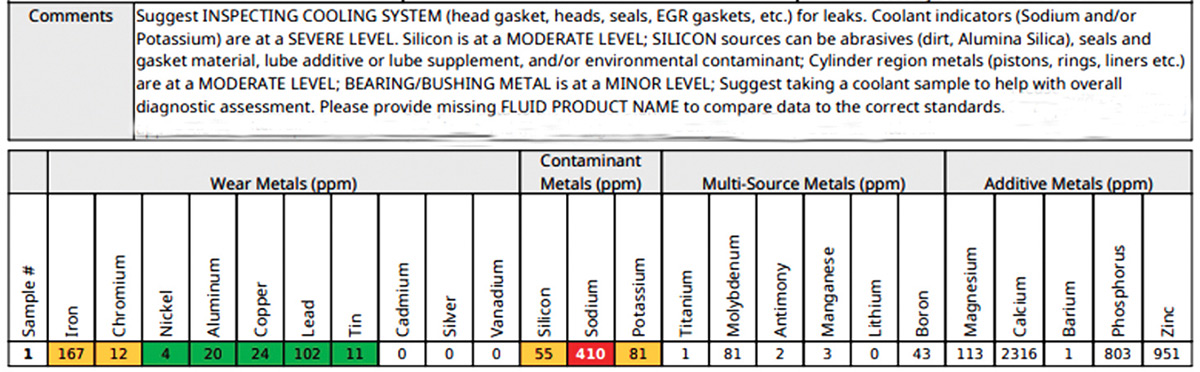

We recently performed our own used oil analysis testing several engines and discovered that one suffered from high levels of sodium, potassium, and silicon that indicated an internal coolant leak. While we had noticed a slight loss of coolant level, this warning forced us to diagnose the problem as an intake manifold gasket failure that was allowing coolant to leak into the lifter valley. We would have been unaware of this problem if not for the used oil analysis warning.

Thicker oil demands that the engine exert horsepower to pump this thicker oil. Many years ago Westech Performance Group performed an oil viscosity test using a 372ci small-block Chevy on the dyno and in one particular case saw a nearly 4 hp increase in average power just by reducing viscosity from 30W to a 0W-20. We saw a similar improvement when reducing oil viscosity on an iron 6.0L LS engine on the dyno.

However, you should not just arbitrarily reduce viscosity without evaluating that change. The best procedure would be to run at least two used oil tests with the current oil viscosity and then run the engine long enough to evaluate a further test to see if the wear metals count increases. If wear metals like bearing material (lead) or iron cylinder wall counts increase, then the change is probably not to the engine’s benefit.

Like most of us, our friend Lake Speed Jr. was skeptical of these claims and decided to test this product on his Motor Oil Geek You Tube program. Valvoline claims this new Restore & Protect oil can reduce overall varnish and deposits after four complete oil and filter changes. Speed employed the SPEEDiagnostix used oil analysis process to measure the results of his testing and discovered that even after only one oil change that much of the visible varnish on the engine dipstick had disappeared.

His SPEEDiagnostix used oil analysis report indicated a higher manganese count in the oil that Speed says is the result of the Restore & Protect oil cleaning the upper ring grooves where this manganese was trapped. This chemical is often employed as an octane booster for gasoline. Speed says that higher levels of manganese in the used oil sample indicates that the Restore & Protect is cleaning the piston ring grooves.

Speed also reported that after testing several engines using Valvoline Restore & Protect that the overall wear rate as evidenced by reduced iron and aluminum counts indicates that this oil is doing a better job of reducing wear. Speed attributes this to Valvoline’s custom formulated additive package.

Unfortunately, this Restore & Protect is currently limited to 0W-20, 5W-20, and 5W-30 API SP–rated viscosities. The 5W-30 is the viscosity for modern LS engines and could be used for older engines like small-block Chevys, especially on engines with tighter bearing clearances and roller lifters. Valvoline does offer a 10W-40 Restore & Protect in Australia, so maybe higher viscosity versions will come to the U.S. as well. We’ll just have to wait and see.

Speed’s test replaced one 15-ounce (1/2 quart) portion of the engine oil with this viscosity improver. Since this product contained only viscosity improvers, this means that it immediately reduced the total additive count of the oil by 10 percent. With 32 ounces in a quart multiplied by 5 quarts, this totals 160 ounces. Substituting this 15-ounce additive means the oil’s total additive count is immediately reduced by nearly 10 percent.

Current API SP gasoline engine oil standards call for a minimum of 600 ppm of phosphorous. Substituting this additive means the ZDDP additive package now falls well short of the API specs. The same lower additive count would be true of any engine oil. This is merely one more reason not to mix additives with existing engine oil.

Our friends at Westech once bolted on a 454ci big-block Chevy where the owner over-filled the kick-out oil pan with an extra 2 quarts. Once up on the dyno, the engine exhibited a drop in oil pressure of more than 10 psi above 4,500 rpm. Dyno operator Steve Brule’ immediately suspected the engine was over-filled and drained a 1/2 quart. When the drop in pressure did not improve, he began removing oil in 1/2-quart increments until the oil pressure stabilized. He eventually removed over 2 quarts of oil from the engine.

By lowering the level of oil in the sump, this radically reduced the windage, which was aerating the oil. When the oil pump attempted to pressurize this oil, the air was squeezed out, which reduced the pressure. Once the oil level was stabilized, less air was entrained in the oil and the pressure normalized at around 65 psi. The point here is that too much oil can be almost as bad for your engine as too little. The culprit in this case was a dipstick not properly calibrated for the oil pan.

If you slowly drain a bottle of new oil that has been sitting for a long period of time and there is sediment or material at the bottom of the bottle, chances are good that the additives are no longer properly mixed. It’s possible they will recombine if you agitate the oil but there’s no guarantee this will occur. The best approach would be to recycle the oil rather than risk losing an engine.

Again, this information came to us from Lake Speed Jr.’s Motor Oil Geek channel. He also tested a sealed can of Mobil 1 synthetic that had been sitting on the shelf at his father’s shop for over 30 years and discovered it had gone bad (oxidized). This shelf-life information also applies to other lubricants like gear oil. The point is to be aware of this and not assume that new engine oil sitting for several years is still able to do its job.

Many enthusiasts mistakenly believe that operating an engine on the rich side is a good idea, but it should now be obvious that this can lead not only to less-than-ideal engine performance but will also require more frequent oil changes. Conversely, running the engine at or near its ideal air/fuel ratio can extend the life of your engine oil. This is one advantage for engines that rely on electronic fuel injection. This assumes, of course, that the engine has been properly tuned. This is another reason why it’s a good idea to add an air/fuel ratio meter to monitor engine’s existing operating air/fuel ratio.

USED OIL ANALYSIS SOURCES

USED OIL ANALYSIS SOURCES ENGINE OIL SOURCES

ENGINE OIL SOURCES