TECH

TECHInTheGarageMedia.com

Photography by THE AUTHOR

Photography by THE AUTHORhere are those among us who were building and driving modified Chevrolets in the ’60s; many of us have a similar affliction as a result—a severe case of selective memory. While the sound and feel of a high-winding small-block hooked to a four-speed transmission was impressive in the good old days, the fact is many contemporary front-drive family cars will suck the headlights out of the cars we still hold near and dear to our hearts. Fond memories are often the result of “The older I get the faster I was” syndrome.

Besides the performance deficit that is a painful reality, many of the performance engines from those bygone days have other shortcomings as well; the 300hp 327 in our ’63 Corvette is a prime example. Back in the day of “high-octane” gas, the 10.5:1 compression and iron heads weren’t a problem, but with today’s fuel, engine-killing detonation can be an issue. In addition, unleaded fuel can cause valve and valve seat wear issues, so arguably the sensible idea is an engine swap.

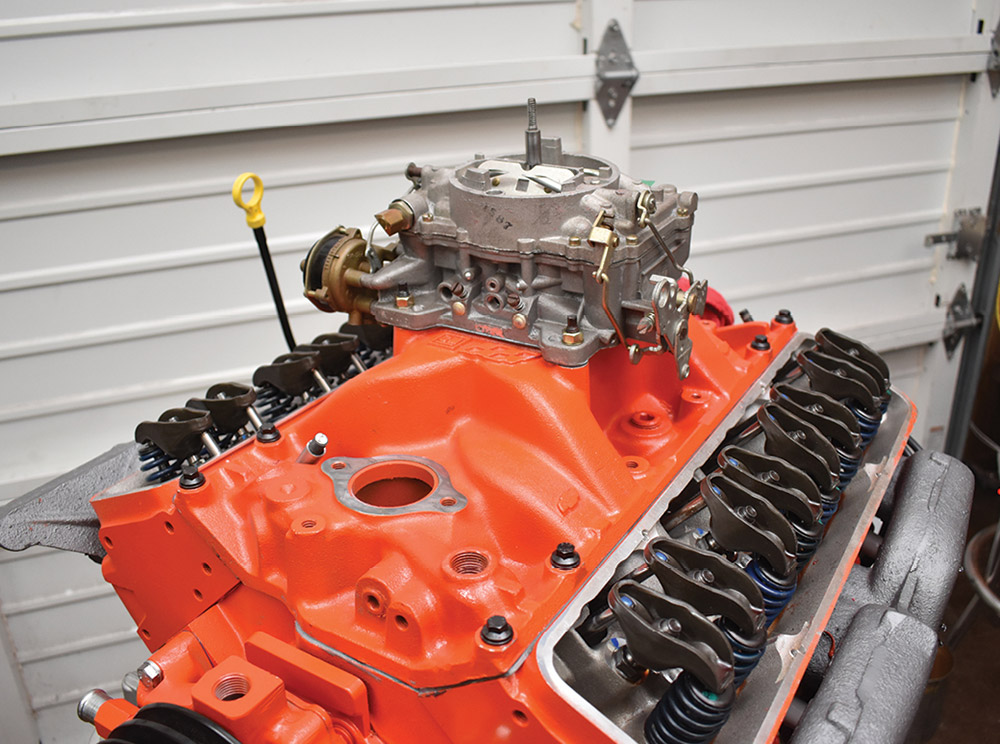

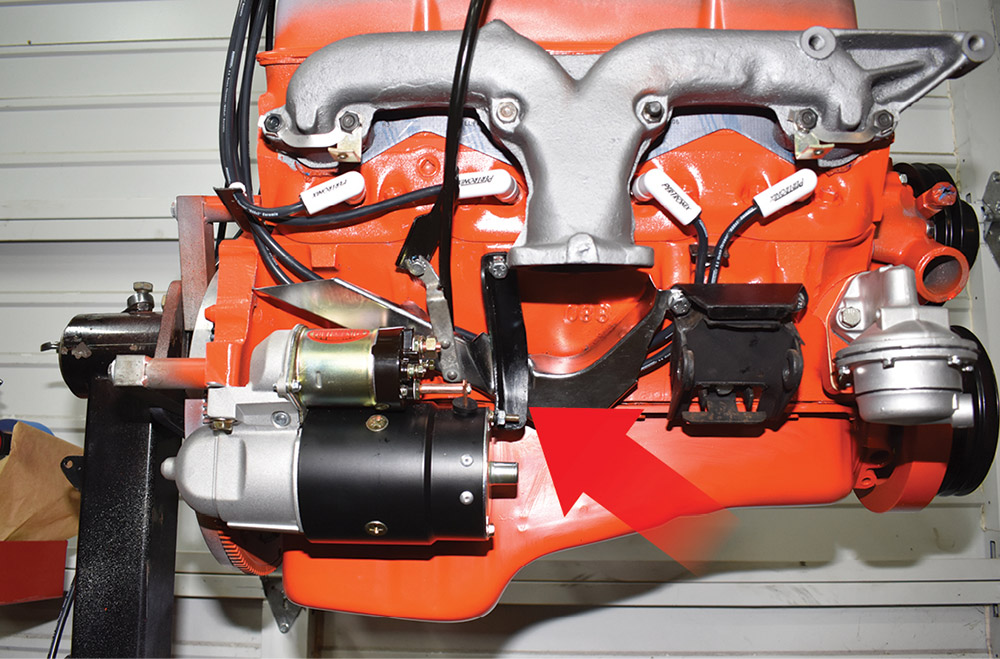

In the age of Chevrolet’s revolutionary LS engines one has to wonder why anyone would choose to repower a vintage car with anything else. But then there are those diehards among us, so we decided on a Chevrolet Performance Gen II small-block because an LS just wouldn’t look right (address all hate mail directly to ACP editor Nick Licata). When it comes to selecting a Chevrolet crate engine, Gandrud Chevrolet has a variety in stock that range from mild-mannered drivers to asphalt shredders. Ours is the SP350/385, the 350ci version that generates 385 hp with 405 lb-ft of torque—that’s 85 more horsepower and 45 more lb-ft of torque than the original 327.

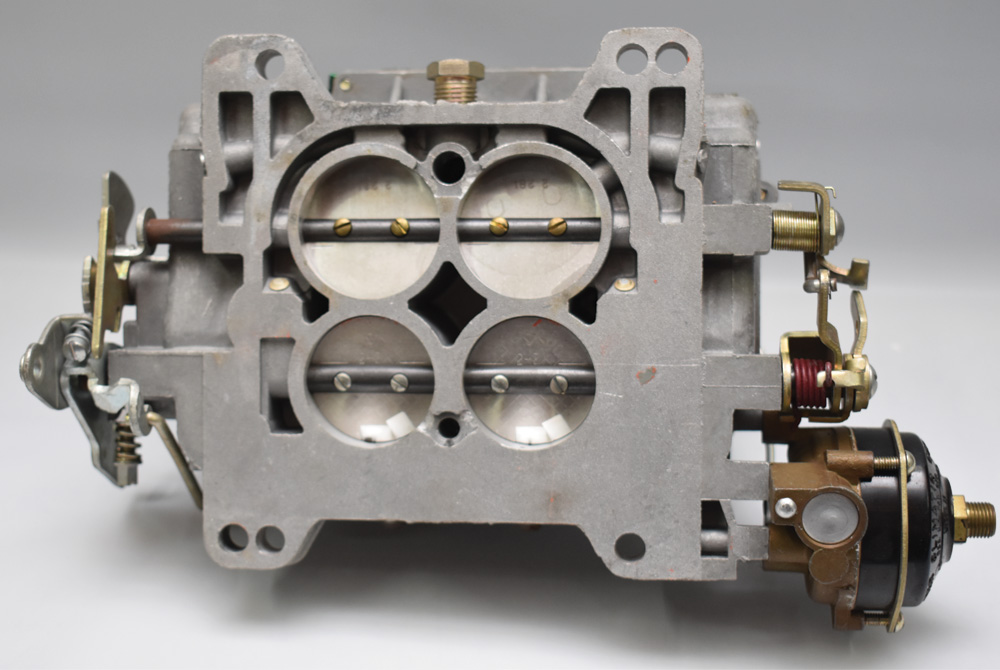

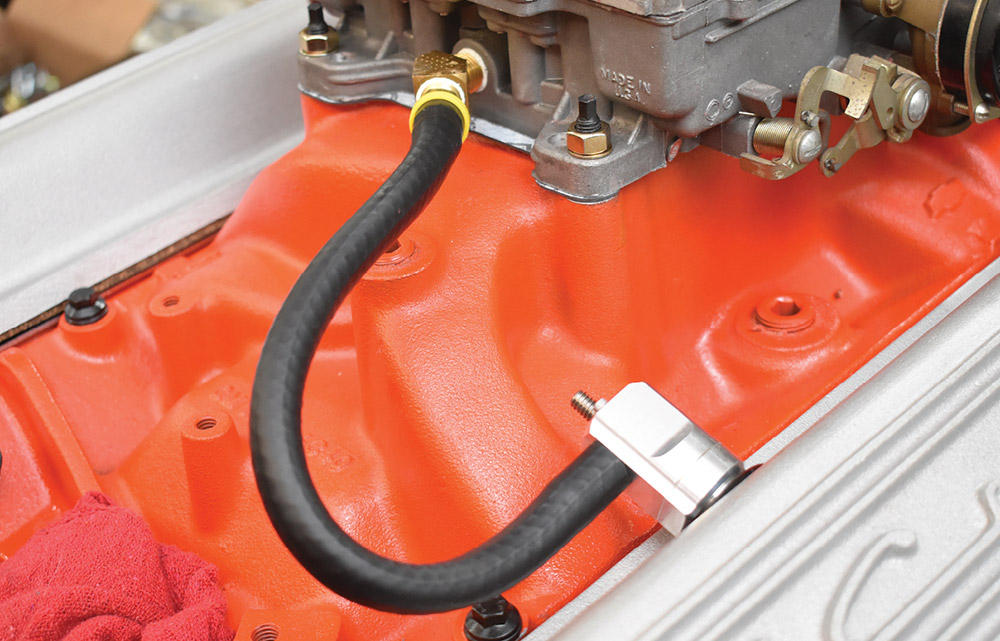

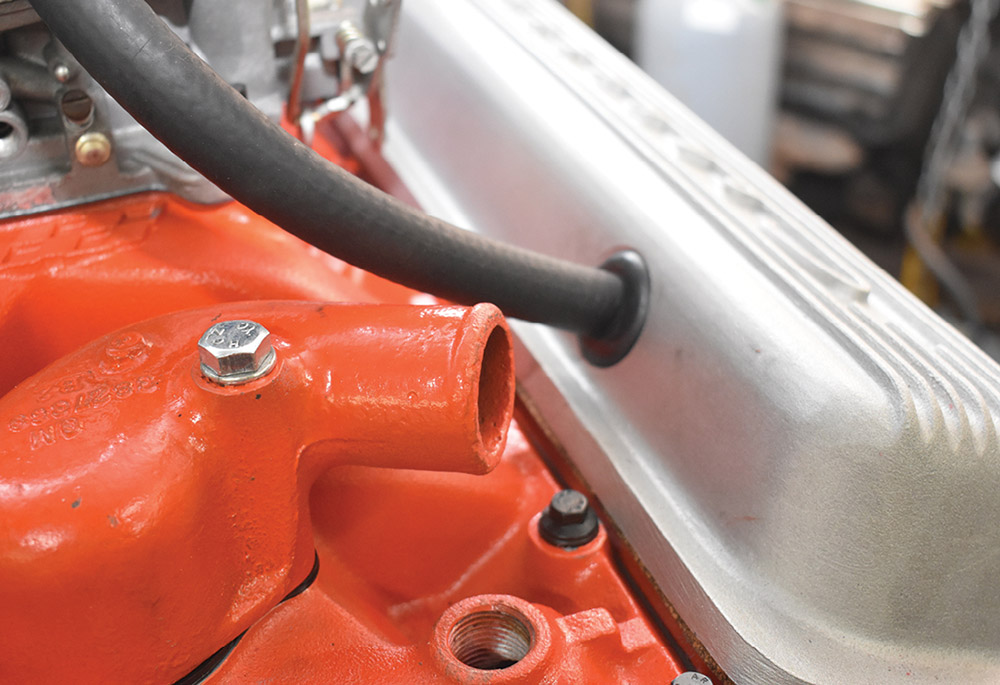

While we aren’t trying to fool anyone, one of our goals for this swap was to maintain the spirit of the original engine, if not the exact appearance. Interestingly, our new engine came with heads that were drilled for the late-style eight-bolt intake manifold as well as the early 12-bolt style. However, while the boltholes line up, our early cast-iron manifold did not match the ports in the new heads. To solve the intake manifold dilemma, we simply used the new aluminum manifold, which did require redrilling the Carter AFB carburetor we’ve had on the shelf since 1977 (proof that you should never get rid of any car parts). However, using the late manifold meant that we no longer had a way to put oil in the engine or introduce fresh air into the engine for the positive crankcase ventilation (PCV) system.

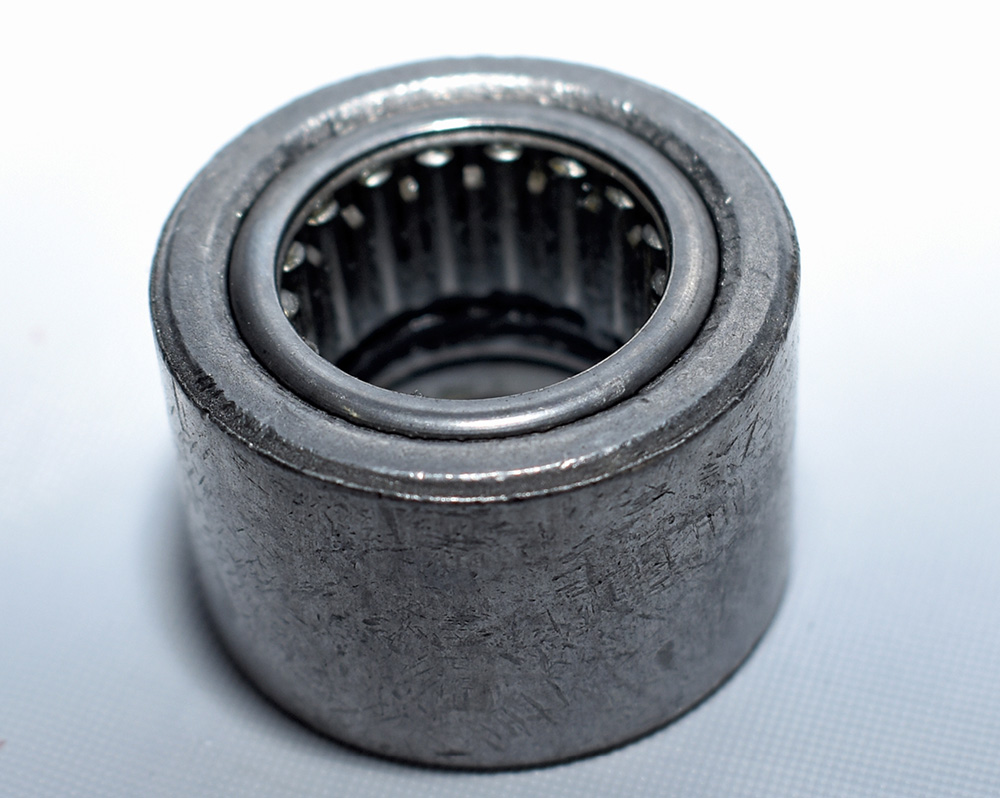

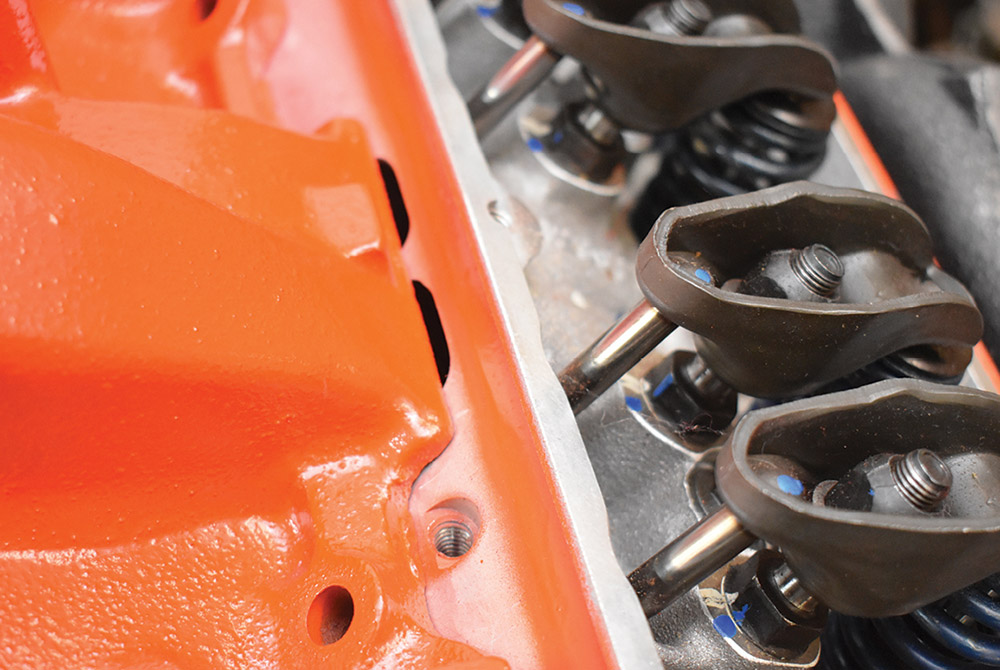

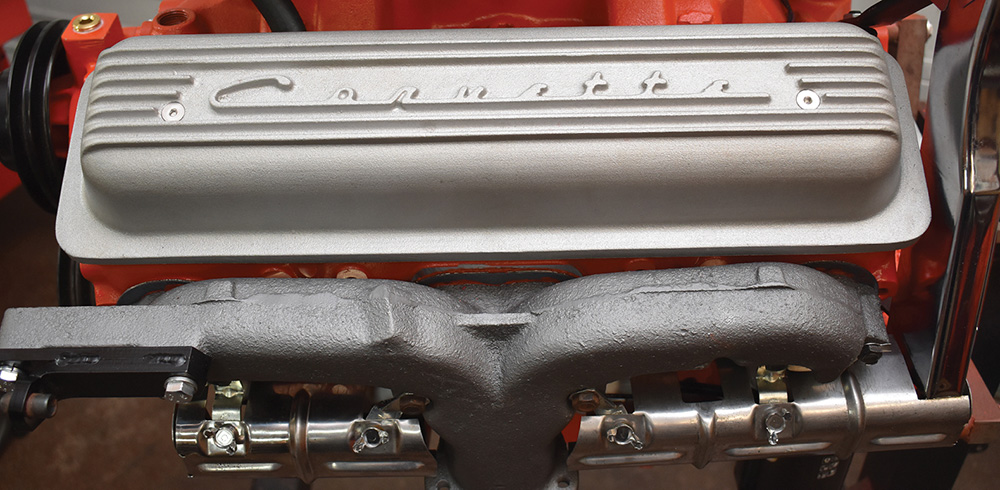

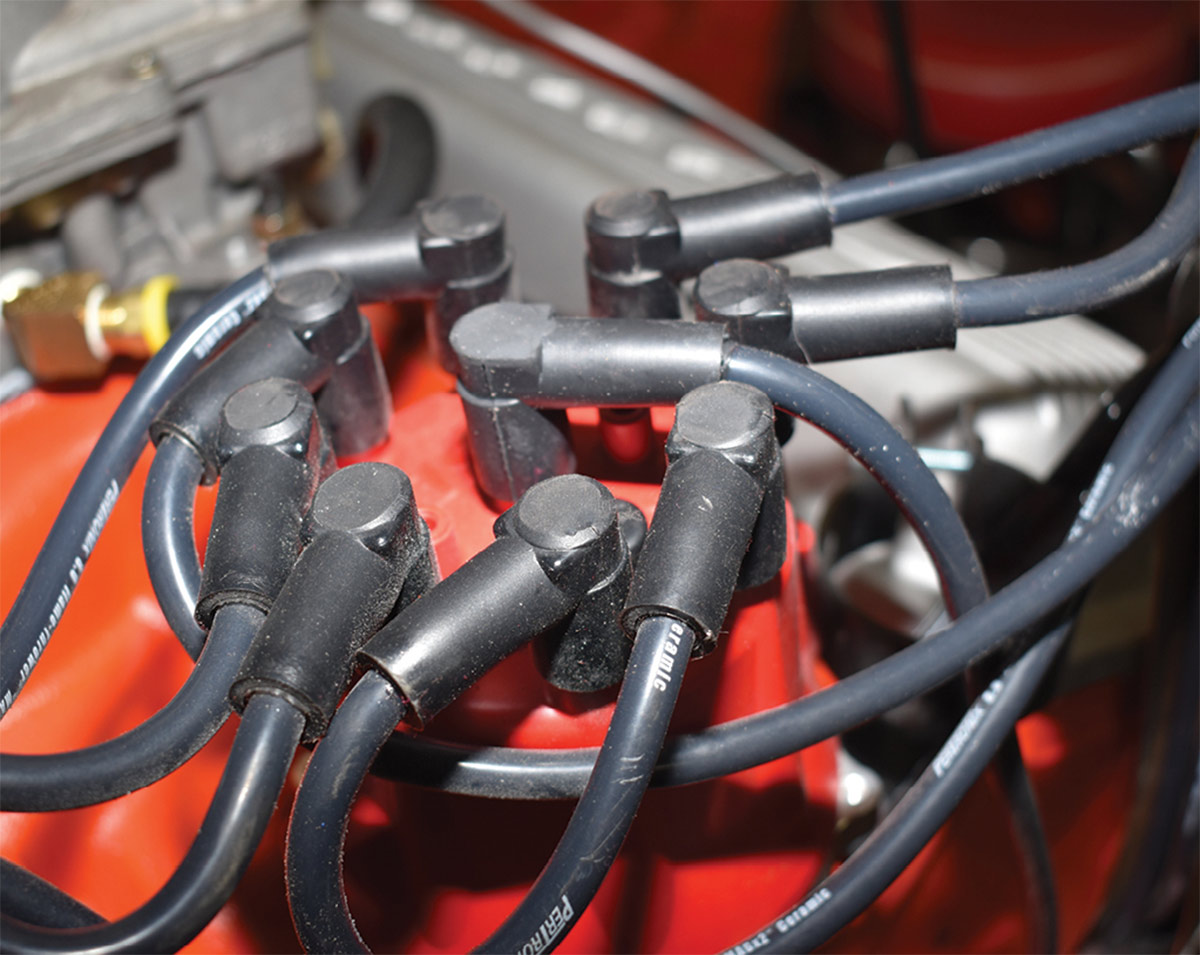

In addition to dual intake manifold attachment points the new heads are drilled for late-style center-bolt rocker covers as well as the earlier perimeter bolt design. Again, the boltholes line up, but the covers won’t work as the pushrod ends of the rocker arms hit the insides of our cool new reproduction covers from Classic Industries. The solution to that was a set of cast-aluminum, Corvette-style rocker covers from PML. Along with solving our rocker arm clearance issues, holes were provided in each cover for the PCV system. Additionally, now oil can simply be added to the engine through one of the grommet holes with a flexible funnel PML provides.

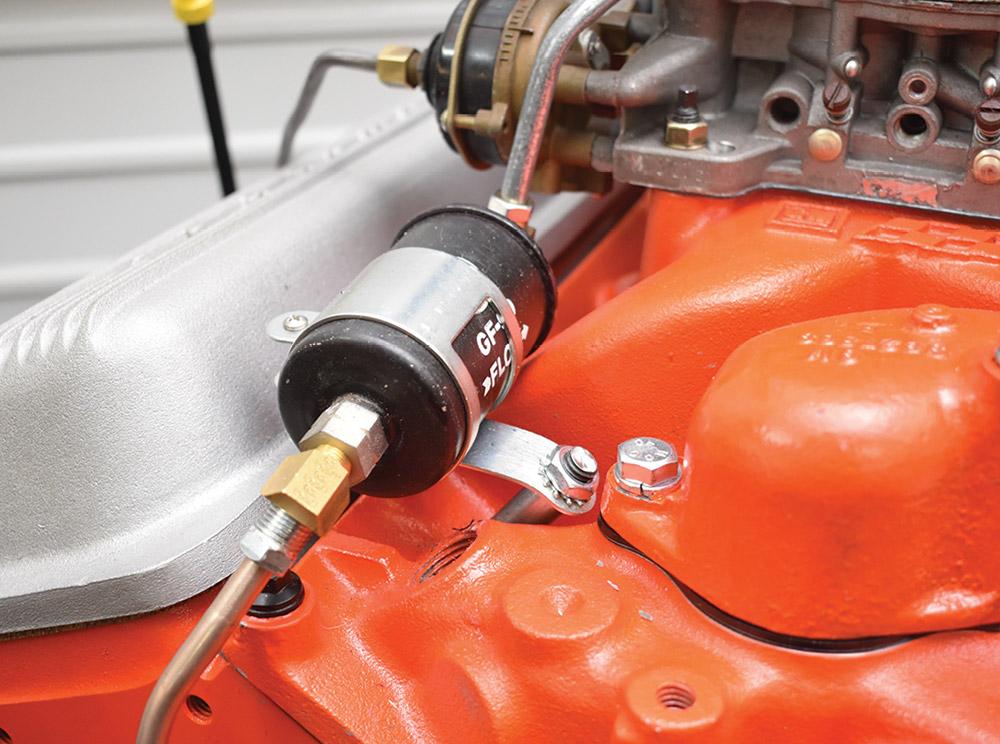

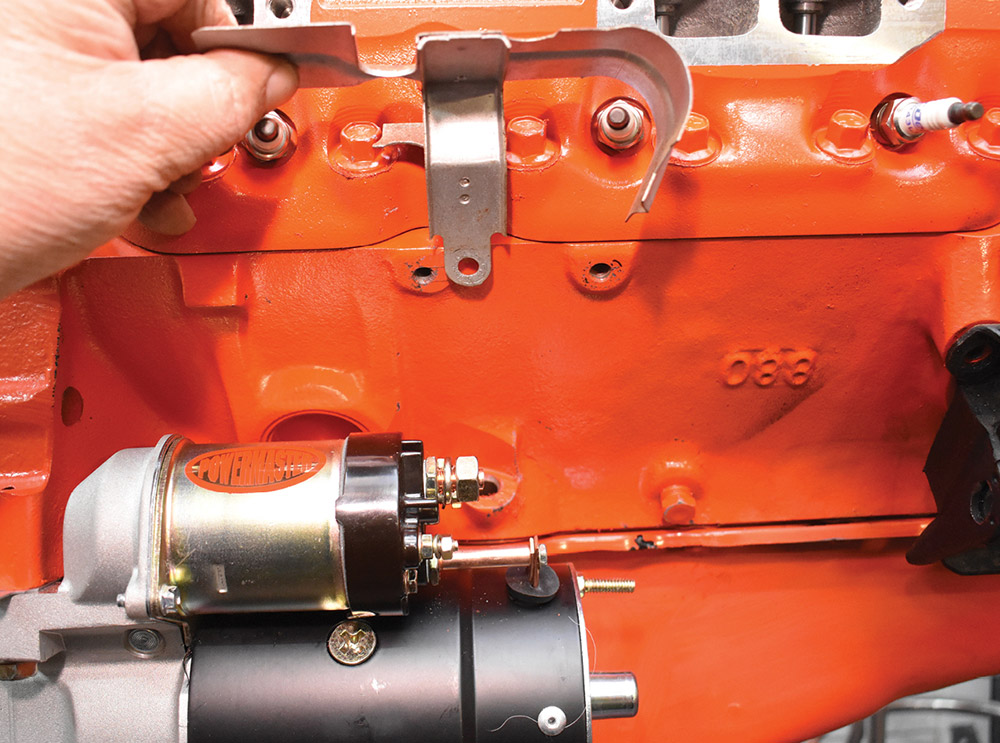

The final touch on our engine swap was to add the original ignition shielding; like most Corvettes, ours used a variety of brackets to mount them. Two for the ignition shield brackets and the one for the fuel filter were originally secured by the original intake manifold bolts, which we no longer had. To address that issue, we used a new intake manifold gasket with both manifold bolt patterns (Fel-Pro 1255) and drilled the necessary holes in the manifold and installed studs to mount the filter and shield brackets.

Our substitute small-block checks all the boxes on the list of attributes we were looking for. We wanted a modest increase in horsepower and torque and an engine that would run on today’s fuel and not look out of place when we opened the hood. We got all that and a 24-month or 50,000-mile limited warranty. The good old days just got better.